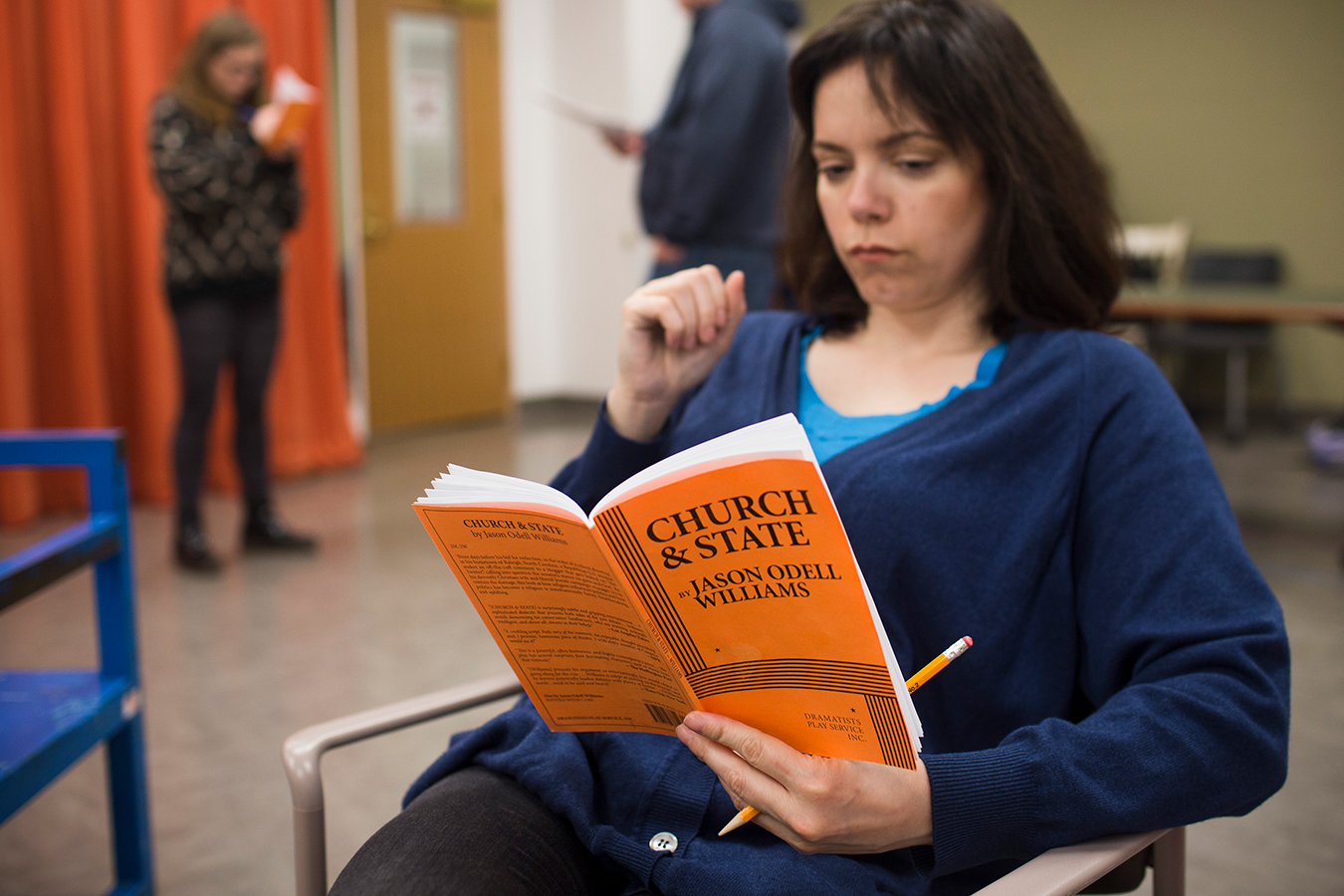

Abby Lee, who plays Sarah Whitmore, during rehearsal for Jewish Theatre of Bloomington’s “Church & State.” | Photo by Chaz Mottinger

According to the play Church & State, “You can’t tell voters what to think.” Politics, like theater, relies on the relationship between the stage and the audience. While that relationship can inspire people to take action, it’s not prescriptive. Neither a politician nor a playwright can tell the audience how to think.

But a play, like politics, can influence. In the Jewish Theatre of Bloomington’s production of Church & State, directed by Liam Castellan, this relationship between the performer — whether actor or politician — and audience takes center stage in a funny and heartrending play with a powerful message about God, guns, and politics.

Church & State is, according to Castellan, “heartbreakingly timely.” When the script was published in 2017, playwright Jason Odell Williams included hope in an artist note that the gun violence discussed and depicted would become so obsolete and irrelevant that it would never be performed again. This is a rather odd wish (like most artists, playwrights typically want their plays to remain long after they are gone), but it speaks to Williams’s desire for a remedy to the gun violence in the U.S.

In the play, a right-wing North Carolina senator named Charlie Whitmore (Steven Hunt) is up for reelection in three days. After seeing the horrors of a school shooting in not just his hometown but also his children’s own school, Whitmore is having doubts about God, the Second Amendment, and himself. Despite his elected position, he feels lost and powerless to stop gun violence. The senator is scheduled to give a speech to his constituency. But to the horror of both his campaign manager and his wife, he wants to go off script and speak out about his doubts.

Wife Sara Whitmore (Abby Lee), a sassy, southern lady with a love for God and her Baby Glock, tries to convince him to reconsider, while Alex Klein (Tess Cunningham), his Jewish, liberal campaign manager, tries to clean up the political mess the senator’s doubts have created.

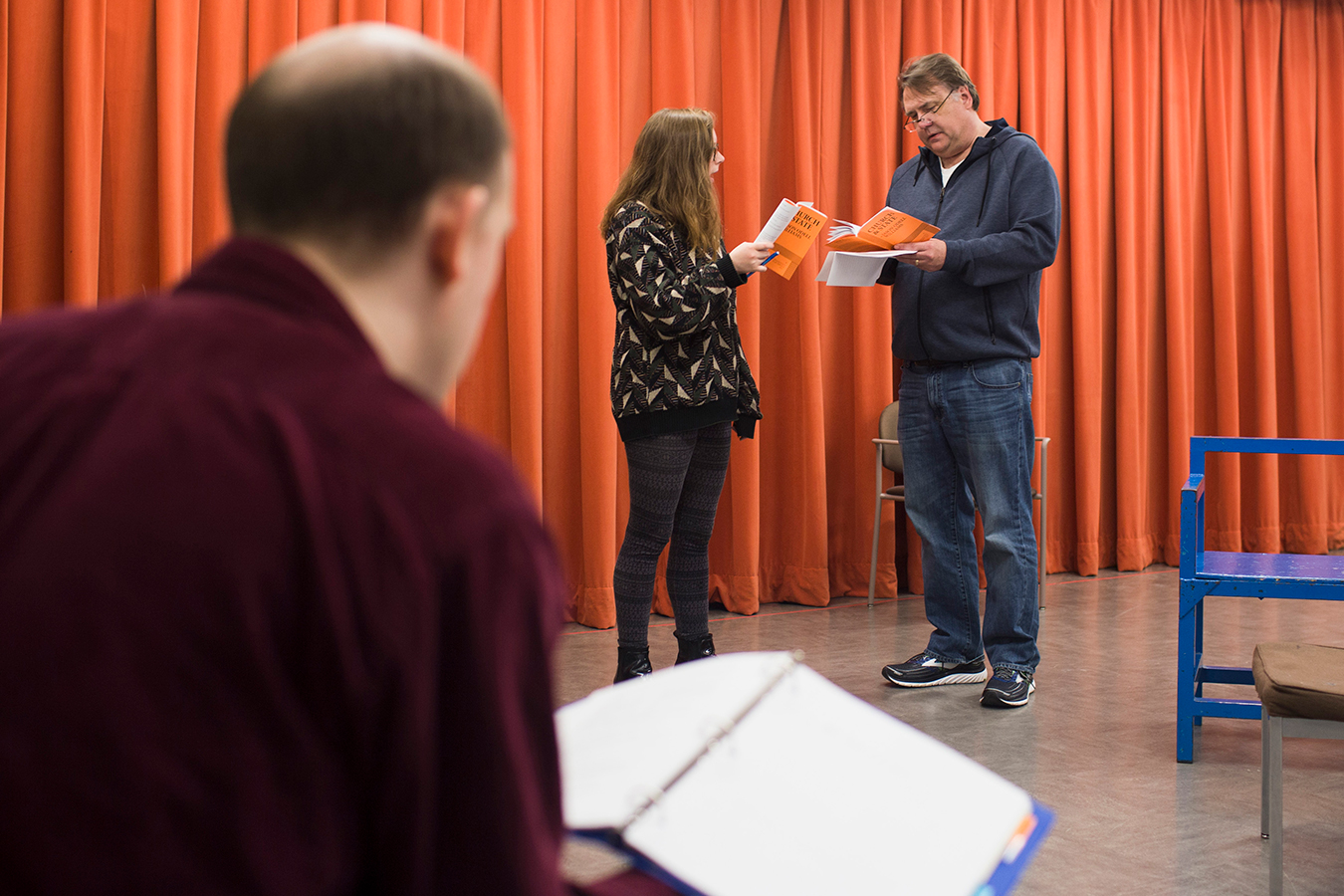

Director Liam Castellan (center) works with Steven Hunt (Senator Whitmore) and Tess Cunningham (Alex Klein) during rehearsal for “Church & State.” | Photo by Chaz Mottinger

As the play highlights, Senator Whitmore’s major fault is not that he’s having doubts — it’s human to have doubts. Instead, his fault lies in believing that he, as a politician, can show that doubt to the public. As Sara points out, “We’re supposed to be an example.”

Castellan finds this performative element at the crux of the play. “I think one of the reasons we rarely see doubt from our politicians in public is because it’s often taken as weakness,” he says. “Certainty is this gold standard.” But the senator goes against that standard, and for Castellan, this is what makes the play so interesting: “It’s fascinating to watch that play out and how that changes him during the course of the play. What’s bold about the play is where Charlie takes that doubt rather than stuffing it in a jar and keeping on with business as usual.”

Senator Whitmore, Sara, and Alex live very public lives, but the play brings us into an intimate, behind-the-scenes perspective as the three interact in a greenroom at North Carolina State’s Stewart Theater before the senator goes out to give a speech. A play is a great venue for a story about politics and political figures because it brings the audience into a private political space where they are privy to the characters’ private thoughts.

The audience gets a rare chance to see public figures, like a senator and his wife, as more than just two-dimensional images of personas with power and agendas. Instead we experience these characters joke, flirt, grieve, and fight with each other. Their performance of the perfect right-wing senator and his wife is thrown aside to illustrate their humanity in the face of tragedy. While we may see a similar humanity in political shows on TV, the liveness of the interaction removes the audience’s ability to keep a comfortable, dispassionate distance, making their relationship to these characters more intimate and, ultimately, more moving.

Castellan’s directorial methodology emphasizes the intimate relationship between performer and audience: “Organizing people to tell the same story collaboratively with the audience — I just find that really exciting. Our ability towards narrative and sharing narrative is just a powerful way to experience our humanity, and remind ourselves of what being human can mean.”

Cunningham and Hunt work through a scene as Castellan looks on. | Photo by Chaz Mottinger

Castellan has a strong cast to help him in his mission. As Senator Whitmore, Hunt gives a relatable face to a common but out-of-reach political character. The audience can see him fighting with his doubt, fighting with his belief in God.

Lee’s depiction of Sara Whitmore is simultaneously strong and vulnerable. She may act like a perfect “sweet and vapid” senator’s wife, but she is as sharp as a tack. Lee really brings out the character’s underlying intelligence and compassion.

Cunningham plays the exasperated and overworked Alex Klein, whose frustration with the senator and his wife is palpable. The small cast is rounded out by Jonathan Golembieki as Tom, a simple but good-hearted North Carolina country boy and a Whitmore supporter.

The play promises to be a funny yet moving production that may not change how people think but will get them thinking and talking. As Castellan aptly summarized, “It’s a play about courage, both political courage and personal courage, and, I think, who couldn’t use a bit more of that?”

[Editor’s note: The Jewish Theatre of Bloomington’s Church & State opens Thursday, May 10, at the Ivy Tech John Waldron Arts Center Rose Firebay Theater. For more information, visit the Jewish Theatre of Bloomington’s website or the Buskirk Chumley Box Office to buy tickets. There will be talkbacks directly after the performances on Saturday, May 12, and Thursday, May 17.]