As the presidential inauguration loomed closer and closer, a group of folks in Bloomington channeled their energy into an event called Inaugurate the Revolution as an act of resistance to the incoming administration. Event organizers curated panels for the one-day conference in order to unite the community in a day of activism and engagement. While options included everything from movie screenings and art workshops to hearing from marginalized communities and learning more about a wide variety of societal problems, we’ve put together four stories showing the many issues people in our town are working on — and what you can do to help out. Our first story is on the importance of media literacy by Elijah Pouges. Other stories in the series include indigenous activism by Laura Martinez and issues (and solutions) involving democratic reforms by Tomi and Jim Allison.

The reasons to be media literate have never been so dire. In the so-called “post-truth” era, we are faced with a president encouraging distrust of a once heralded institution — the news media. While the term media can refer to a variety of sources of information consumption, effectively navigating the daily news cycle and understanding its messages are integral to getting the most from it and recognizing what is “normal” in our society. The media is not something to be passively absorbed, but to be engaged with. This is especially important considering how the media affects marginalized groups.

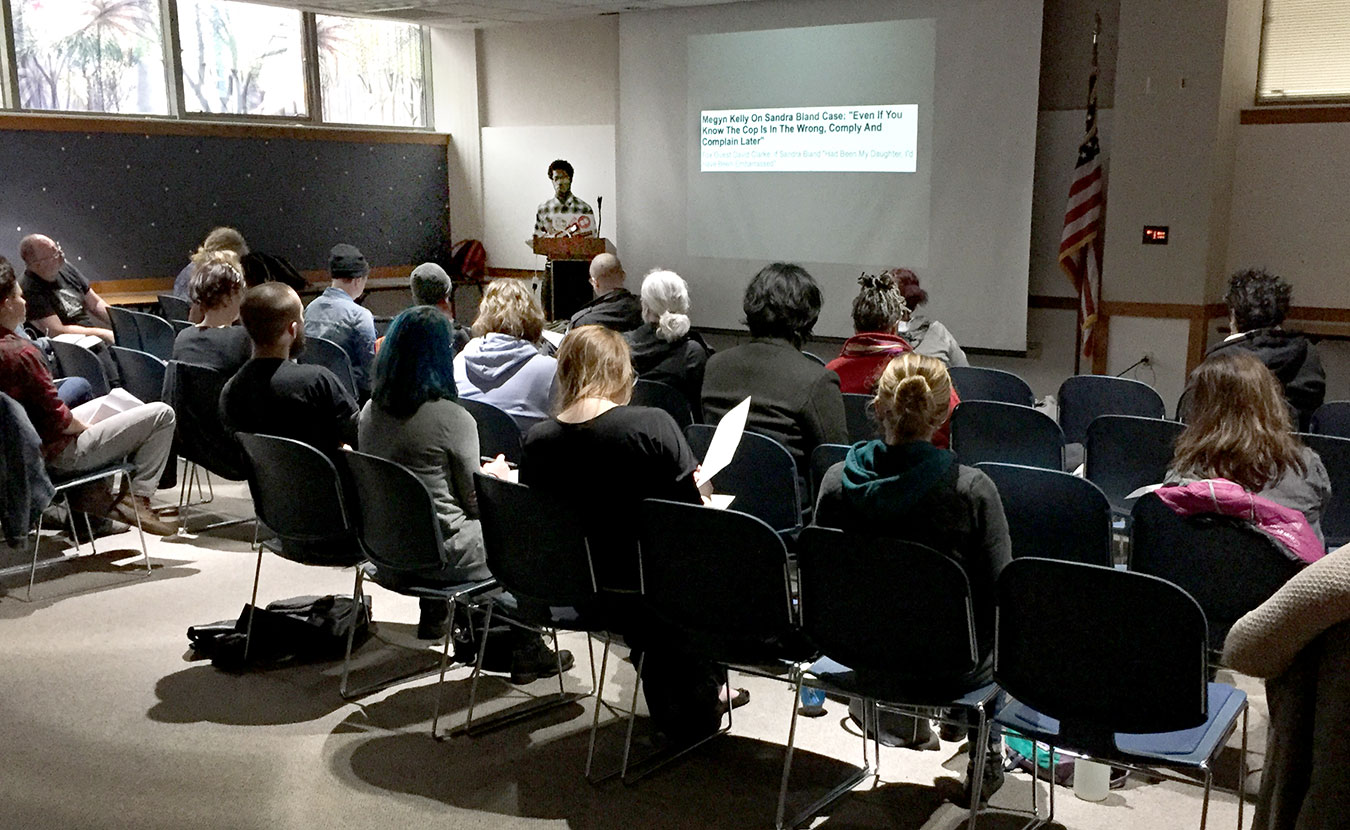

Pouges says learning when news sources frames stories for their own agenda can help people become better consumers of the media. | Limestone Post

When talking about media literacy and oppression, one must first consider what it means for information to be “framed.” Framing theory, which is often attributed to sociologist Erving Goffman, essentially states that media not only interprets information for an audience, it also influences how the audience interprets the information and what messages the audience can derive from a story. This becomes dangerous, especially when media may be promoting nationalistic, racist, or xenophobic rhetoric.

Katrina Overby, a doctoral candidate and assistant instructor at Indiana University’s Media School, agrees with this notion. “Everyone has an agenda — that’s why news is created,” she says. “Anyone can absorb messages. [But] how you interact with the media is important.”

When confronted with a piece of news, consider what the headline is telling you, then reflect on any images that accompany the text. Observe how all parts of the story work together, especially if the story features people of color or another historically marginalized group. What is being omitted may be more important than what is being reported. A recent headline from a story reported by an ABC affiliate station in California read: “Duo gets prison time for racial slurs at black child’s birthday party.” This headline, which has since been updated, failed to include that the individuals charged were armed with weapons, threatening real violence to black bodies. A headline such as this trivializes the nature of the case by omitting crucial details needed for an empathic reading.

To recognize what is being left out of a story, and to help fine-tune one’s media literacy skills, diversification is key. Like a fine ensemble of instruments creating harmonious music, a plethora of credible news sources give the media-literate consumer a better understanding of the world.

The Critical Media Project, a resource created at the University of Southern California Annenberg, defines race and ethnicity as social constructs imbued with pre-existing meaning. Due to colonization, it was often the case that whiteness would establish itself as the social standard, while people of color were ostracized and made subordinate in the social order. This narrative, through the Western lens, is often perpetuated in the media; this idea not only applies to race, but any social dynamic where a group establishes economic or political control and exerts this power onto a subset of society.

Suddenly realizing that a favorite media source is promoting oppression, be it implicit or explicit, can be jarring. It can create a dissonance within the consumer that borders on discomfort. Embrace this feeling, as it means you are beginning to see new perspectives on a subject and can recognize and critique media that is perpetuating a harmful narrative. One way to begin seeing new perspectives is by recognizing the framing of story, and making a mindful decision on what you feel about the information being presented.

As Monica Johnson, director of IU’s Neal-Marshall Black Culture Center, puts it, “There is a lot of autonomy in deciding how you feel about something.”

No Replies to "Becoming Media Literate in a ‘Post-truth’ Era"