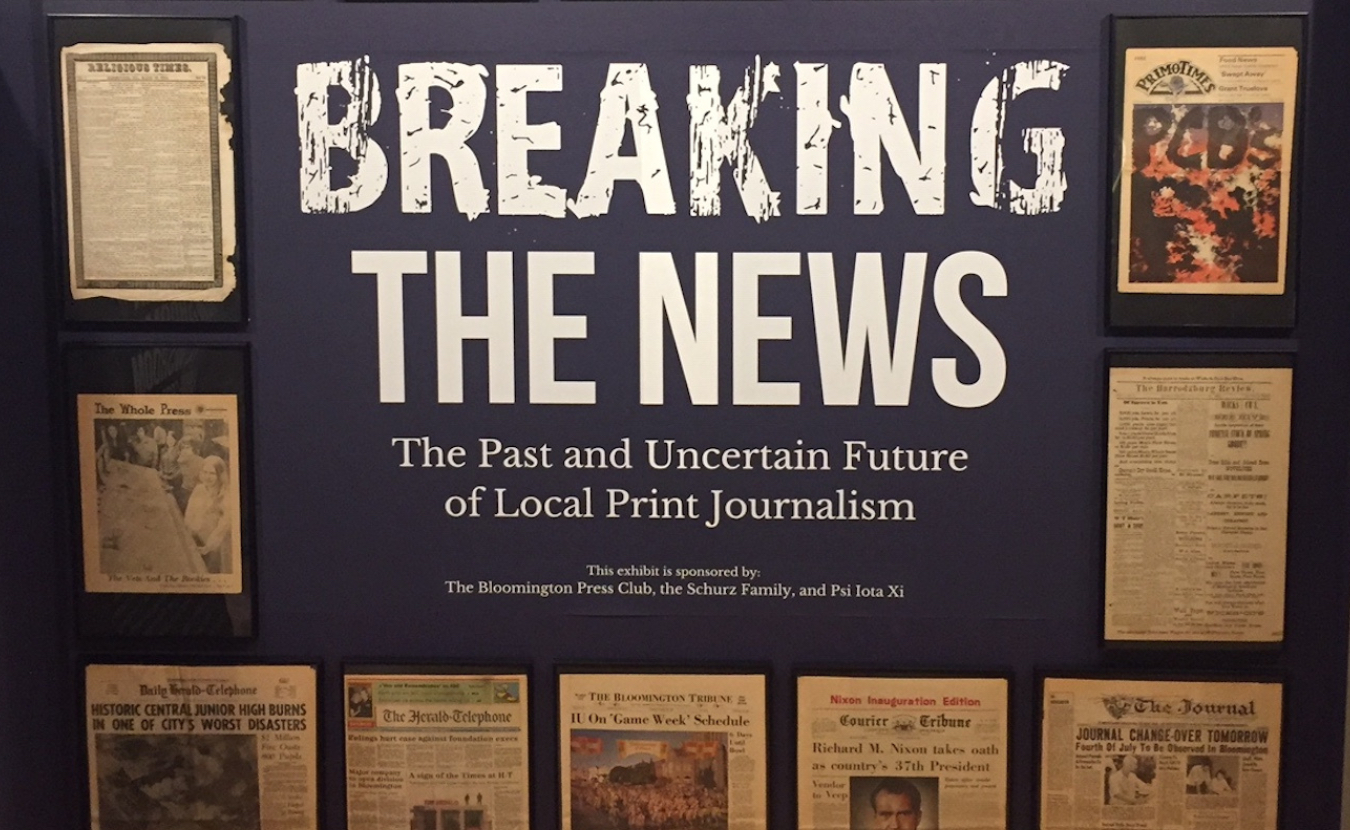

Visiting the “Breaking the News” exhibit at the Monroe County History Center filled me with a mix of emotions. Seeing the long, rich history of news reporting in our community made my heart swell with pride that I am part of this important community service. Rounding the corner to the glory days of The Herald-Telephone/The Herald-Times, though, evoked sadness at what our once proud newspaper has become. Standing at the end of the MCHC’s largest exhibit to date, I looked at the question we are all challenged to ponder: What is the future of local news?

At my first newspaper gig, a cub reporter learning a beat, learning to play nice with my editor (I actually didn’t learn that one), learning where to find information, I also learned about wistfulness and longevity. One of the long-serving reporters lamented the days of golden watches at retirement parties and, at the very least, catering for Christmas. If only he could have seen 15 years into the future, where now the newsroom I came up in has two employees. When I went to work there, the company had just built a new building on top of a hill. The newsroom had around 15 people and there were advertising reps and press guys and HR and business people — everything one expects a workplace to have.

Making room for better reporting

I left journalism, but this city lured me back. I had subscribed to The Herald-Times for years before I worked there. I remember calling former editor Rich Jackson on the phone to ask what the heck was going on. The H-T had published the same story on two different pages and the editing was atrocious. (I know we’re not much better these days, and for that I am sorry. I am doing the best that one person can.)

I went through a life-changing experience, one that made me question my purpose, my goals, and my willingness to do hard things. I found myself on the other side with a better understanding of gratitude and service to my community. The job opening as news director at the H-T spoke to my experience and I entered with the confidence that I had something to offer my community by doing this very difficult job.

“It was sad walking into the H-T building,” says Bond. Many of its offices had become empty before the newspaper’s corporate owners sold the building on South Walnut Street. | Limestone Post

It was sad walking into the H-T building, although I suppose I got used to the emptiness. The newsroom had already moved from the back of the building to a small corner near the front, where some natural light streamed in. The door, locked during COVID, remained so because none of the services people used to access — billing, paper rolls, subscriptions — were left.

I began by listening. I asked what everyone did, and what took time away from the core mission of reporting news. I asked what the staff members thought was valuable to the community and what they thought we could all get used to doing without. I started clearing things off desks, metaphorically and later literally, to make room for better reporting. I took the cues on what was working for today’s digital audiences and applied them to the lens we use to examine which stories to do and when to publish them.

For a while, I thought things were really going well. I felt like we had enough resources to serve this community’s interests, provide the comprehensive coverage we’re all craving, to sift through the viral turtle hoaxes and questions about the powerful entities that influence community outcomes. We were on track to deliver well-researched, fact-based articles that were unique to us and rooted in the belief that the newspaper’s greatest purpose is putting people at the center of everything we do.

As soon as I started, the H-T staff shrunk some more as our design team was dissolved. But what was left to us was enough. There were essentially 14 people at that point, a few of them shared between our site and others.

It didn’t last long.

In just over two years, the H-T is down to eight.

And now it appears we are surrounded by news deserts. There are nearly no reporters left in Owen, Greene, Lawrence, Brown, or Morgan counties. A new weekly is gearing up to serve the news needs of Morgan County, and papers still exist in all the areas surrounding us. Without reporters, though, who is there to ask tough questions of those in power?

Newspaper auction

I have grown increasingly concerned about our city’s access to news. So concerned I opened an account at the Community Foundation of Bloomington/Monroe County to start collecting donations to fund local reporting. I am hoping to put money into that fund through an auction of the newspaper archive once owned by The Herald-Times.

In our old building, there was a large room: creepy, terrible lighting, a musty, mildewy smell, a mess of disorganization, and a magical place to visit. This was “the morgue,” the place where the collection of old editions told the story of everything that ever happened in Monroe County.

The archive consists of more than 1,100 books of newspapers, spanning about 100 years of our collective history. A copy of each day’s printed paper, month after month, year after year, was bound together in a 2-foot-by-3-foot hardcover book.

Books of old newspapers were stored in a room — known as “the morgue” — in the basement of the former Herald-Times building on South Walnut. The books are now stored at Cook Medical, where they await auction. | Photo by Jill Bond.

When I joined the staff of the H-T, the books’ future was of great concern. When newspaper buildings and offices in other towns were closed, a community steward was found, often the local historical society. Naturally, we began by offering the books to the Monroe County History Center, which already had begun the process of collecting our photo archives and selecting artifacts that are now part of the “Breaking the News” display.

But it was too much. The sheer volume of materials prevented the history center from accepting our books.

I didn’t stop there. I connected with Indiana University Archives, the Indiana State Library, and the Monroe County Public Library. MCPL conducted an inventory of the books, which made it easier for the state library and IU Archives to review our holdings and compare them to what they each already possessed. The oldest, most delicate papers were from before 1918, and those were transported to the state library, which has the ability to preserve them for the future, despite their condition.

The day finally came when a member of the corporate team was to arrive to begin closing the building and moving us out. The books had been moved to pallets, but they were still in the building with no destination.

Members of the leadership team offered no solutions for long-term storage and instead suggested they be discarded. It was a heartbreaking thought.

Cook Medical came to the rescue. Cook agreed to store the books for us and has done so for several months. But this is not a permanent solution, and the only thing left is to try to support local journalism by selling them.

These books will be offered in an online auction August 25 to September 13 by Estate and Downsizing Specialists LLC (EDS), a local collectible auction house that has generously agreed to forego any percentage of the proceeds, collecting only a buyer’s fee.

Before EDS can list the books, we need volunteers who can give a few hours to sort them and look for some of the most important moments in history. If you are available between now and September 15, email volunteer coordinator Janice Rickert at [email protected]. We need more help.

“

Without reporters, who is there to ask tough questions of those in power?

”

The Local News Fund at the Community Foundation will be the recipient of any proceeds from this sale. This deposit account is intended to be spent within the next few years to support expansion of local news. I have some ideas on what our community could do with the funding, but it will be the Community Foundation board that ultimately decides how the money is best spent.

You don’t have to buy one of the books to support the Local News Fund. You can see its purpose and make a donation right now at the Community Foundation’s website.

The news desert surrounds us, but that doesn’t have to become our fate. If we band together, we can regain local control of access to information about our community.

The auction will be live August 25–September 13 at edsindian.hibid.com/auctions.