Nearly one in three white, Protestant men in Indiana were members of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) in the early 1920s. They came from all walks of life: lawyers, preachers, legislators — including Governor Ed Jackson — and everyday folk. And they put on robes and hoods and burned crosses throughout the Hoosier state.

As Indiana University Professor Emeritus of History James H. Madison reports in his book The Ku Klux Klan in the Heartland (IU Press, 2020), the membership grew quickly and infiltrated all levels of government. Some Klavern members attended Sunday church services wearing robes and hoods and offered donations. Women organized separately, as Women of the Ku Klux Klan. A photo of a funeral in the book shows the deceased member’s robe on her coffin. Even female preachers supported the Klan’s militantly Protestant message. Daisy Douglas Barr, a Quaker minister, traveled through central Indiana promoting the KKK.

In ‘The Ku Klux Klan in the Heartland,’ James H. Madison, Indiana University Professor Emeritus of History, wrote that the Klan story ‘rests at the core of American history, not at the margins.’ | Image courtesy of Indiana University Press

The KKK attracted those who claimed they were “100% American.” In a fairly homogeneous state like Indiana, that meant the exclusion of Blacks, Jews, and Catholics. Catholics, many of whom were recent immigrants, were suspect for their allegiance to the pope as a foreign power.

In some ways, that view of who is an American is reflected today in various political, militia, and hate groups. In their book Taking America Back for God: Christian Nationalism in the United States (Oxford University Press, 2020), authors Andrew Whitehead and Samuel Perry surveyed Americans from all walks of life. Whitehead is an IUPUIassociate professor of sociology and director of the Association of Religion Data Archives at the Center for the Study of Religion and American Culture.

Whitehead’s book places respondents into one of four categories, on a scale of most supportive to not supportive of Christian nationalism: ambassadors, accommodators, resistors, and rejectors. For ambassadors, “Christian nationalism is fundamentally about preserving or returning to a mythic society in which traditional hierarchical relationships (e.g., between men and women, whites and blacks) are upheld, and authority structures are biblical and just.” Fifty-one percent of those Americans surveyed fell into the ambassador or accommodator category.

“Many Americans embrace Christian nationalism, and obviously not all or even close to many would embrace the KKK or are white supremacists,” Whitehead says. “But I think you could say that for many white supremacists, Christian nationalism is a key part of that undergirding ideology.” Whitehead’s data show there is a strong Christian nationalism presence in the Midwest, though the strongest representation in the U.S. is in the South. As might be expected, far more people who identify as conservative and Republican support Christian nationalist beliefs. The majority of the ambassador group are white women older than 54 and live in rural or small towns, reflective of much of southern Indiana. Christian nationalism is widespread and widely accepted, though declining as the numbers reflect from a 2007 survey he references in the book.

Many current Indiana hate groups that are tracked by the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) and the Bloomington group No Space For Hate (NSFH) have some aspect of Christian nationalism, white nationalism, or racist beliefs. Far-right groups such as the Proud Boys and Oath Keepers define themselves as defenders of the Constitution and therefore are “true Americans,” just as the KKK once did.

In ‘Taking America Back for God: Christian Nationalism in the United States,’ authors Andrew Whitehead and Samuel Perry write, ‘Christian nationalism is fundamentally about preserving or returning to a mythic society in which traditional hierarchical relationships (e.g., between men and women, whites and blacks) are upheld.’ | Courtesy image

By the end of the 1920s, Hoosier KKK membership cratered. Part of this decline was due to the arrest, trial, and imprisonment of D.C. Stephenson, a salesman and the Indiana KKK’s Grand Dragon, for rape and murder in 1925. By 1927, Stephenson was talking to reporters about legislators who were card-carrying KKK members, and people fled the organization.

When the KKK tried to revive membership in the 1940s, state legislators were quick to pass an anti-racketeering in hate law in 1947. Groups could not conspire, organize, or associate for the purpose of spreading malicious hatred by reason of race, color, or religion. Violators could get up to two years in prison and a $10,000 fine.

The law was repealed in 1977.

NSFH researcher RG Reynolds says the passage of the 1947 law showed the power of legislation in keeping hate groups at bay. KKK membership numbers did not increase again until the 1960s, though it never matched the popularity of the ’20s.

Part of the appeal of the early Indiana Klan was the festival atmosphere for gatherings, as well as the camaraderie of the group. Burning crosses lit the night sky on Christmas 1922, with displays across the state, including in Bloomington, Indianapolis, and Bedford. Perhaps the largest display of Klan representation was a parade with nine bands, food, games, music, and an appearance by D.C. Stephenson at Kokomo’s Melfalfa Park on July 4, 1923.

But as Madison says in The Ku Klux Klan in the Heartland, “The two major distinctions between the Indiana Klan of the 1920s and today are the radical differences in numerical strength and the resistance that now arises with the first scent of a burning cross. Strong resistance began in the years after World War II and expanded in the 1960s. By the late twentieth century, it was easy to denounce the Klan. Still not so easy has been rejecting small-minded tribalism and us-versus-them divisions, understanding the privileges white men enjoy, and learning the values of democracy for all. The Klan story does not give comfort. It rests at the core of American history, not at the margins.”

Racism and antisemitic views didn’t recede with the weakening of the Klan. As Black Lives Matter Bloomington core council members note, systemic racism has been a constant presence, even if major physical threats are not prominent in Bloomington or even in Monroe County. “We’re not talking about history coming back, we’re talking about a continuation of the marginalization of African Americans, indigenous people, and other people of color,” says council member Jada Bee. “We’re not talking about a revival. It [racism] has always been there.”

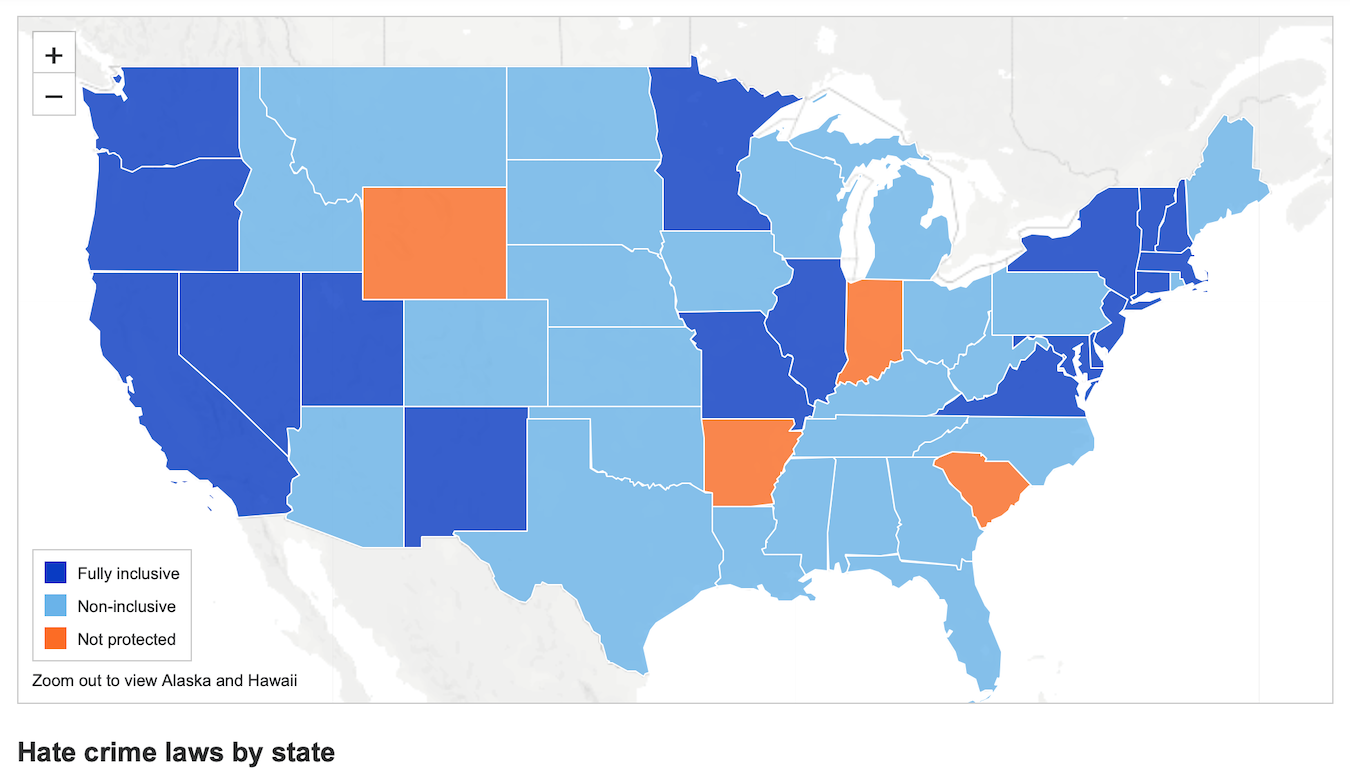

This Anti-Defamation League map shows hate crime laws by state. Such laws can address ‘hate crimes directed against individuals because of race, religion, ethnicity, sexual orientation, disability, gender or gender identity.’ Indiana is one of only four state with no such laws.

Yet hate crimes have risen in recent years, and hate crimes based on religion spiked in 2019, according to the ADL’s Tracker of Antisemitic Incidents, which tracks hate crimes by state. The ADL reported the most crimes since they began tracking in 1979. In 2019, 60 percent of religiously motivated hate crimes targeted Jews, though Jews represent less than 3 percent of the total U.S. population. The ADL Hate, Extremism, Antisemitism, Terrorism (H.E.A.T.) map records several incidents in Bloomington in 2019 and 2020, including the Patriot Front, an alt right group, distributing propaganda at IU in July 2020, which read, “America first,” “life liberty victory,” and “For the nation against the state,” as well as an unknown person driving by an outdoor Yom Kippur service in September 2020 and yelling antisemitic statements at attendees.

Alvin Rosenfeld, IU professor of Jewish Studies and director of the Institute for the Study of Contemporary Antisemitism, defines two types of antisemitism. Social antisemitism finds Jews disagreeable or unlikeable, and its goal is to marginalize Jews. Political antisemitism is not just a dislike of Jews but a fear of Jews taking over the political system, financial systems, and the media. It is usually political antisemitism that turns violent. “Antisemitism is a growing fact of life in this country,” says Rosenfeld. “It needs to be taken seriously.” He notes that antisemitism doesn’t exist in isolation. Instead, it rises in periods of social unrest and when economies are down, and people are looking for scapegoats.

Researchers at the Bloomington group No Space For Hate monitor social media and online groups for racist, anti-LGBTQ, and antisemitic chatter. They report more than 31 hate groups active in Indiana.

No Space For Hate researchers monitor social media and online groups for racist, anti-LGBTQ, and antisemitic chatter. They report more than 31 hate groups active in the state, and virtually all of them have some tie to a national organization. Indeed, by early March, of the six Hoosiers arrested in connection with the January 6 riot at the U.S. Capitol in Washington, DC, five were from central or south-central Indiana, including two women from Bloomfield. Reynolds says the Oath Keepers and Proud Boys are two groups that have gathered the most membership and potential for violent activity in southern Indiana. Paraphrasing the words of John Stuart Mill — “Bad men need nothing more to compass their ends, than that good men should look on and do nothing” — Reynolds says the sure way for hate groups to expand is “for good people to do nothing. Social media has given them a new platform and a digital landscape in which to spread their propaganda, but the problem remains that the idea of hate speech itself has become the sort of rallying flag for these groups.”

How these experts and groups tackle the issues of today’s racism vary. BLM Bloomington believes in education, to help people understand how systemic racism affects the entire community. No Space For Hate wants people to speak up and speak out against the racism, antisemitism, and anti-LGBTQ rhetoric, as well as support anti-hate legislation. Rosenfeld says it is a four-prong approach: through changing hearts and minds by education; creating strong anti-hate legislation; electing good leaders who do not support or promote hate group agendas; and, finally, realizing that the internet is the single biggest disseminator of hate.

As Madison notes in his book, “Governor Ed Jackson had descendants among politicians willing to dance with the devil as they pretended to work for the people. And there remain those who believe their particular version of God and nation ought to be forced on all. Such descendants are far removed from the Klan of the 1920s, but anyone with historical antennae checks the landscape for white robes and burning crosses, even if only metaphorical and even if hidden under pressed blue shirts or silk blouses with sleeves rolled up to redeem the nation.”

Far-right groups such as the Proud Boys and Oath Keepers define themselves as defenders of the Constitution and therefore as ‘true Americans,’ just as the KKK once did. Alt right group Patriot Front distributed propaganda at IU in July 2020, which read, ‘America first,’ ‘life liberty victory,’ and ‘For the nation against the state.’ Above are logos of the three groups. (l-r) Oath Keepers, Patriot Front, Proud Boys.