Judith Arcana was in her 20s when she learned how to perform an abortion as part of the underground Chicago Abortion Counseling Service of Women’s Liberation. Using posters that said “Pregnant? Don’t want to be? Call Jane,” the service answered a multitude of calls received from women who wanted abortions.

As a Jane, Arcana counseled hundreds of women, drove them to Jane-leased apartments and, later, did the procedure herself.

Judith Arcana in 1970 and today. In her 20s, she was a “Jane,” part of the underground Chicago Abortion Counseling Service of Women’s Liberation. | Courtesy photos

Months before the U.S. Supreme Court decided on Roe v. Wade, she and six other Janes were arrested on 711 counts of performing illegal abortions and conspiracy to commit abortion. When the Roe v. Wade decision was publicized, they were released. Overall, the Janes performed more than 11,000 abortions.

Bloomington, too, had a similar underground group, Midwest Abortion Counseling Service (MACS). IU student Ruth Mahaney started the service after hearing about her friend’s attempt to get an abortion: The physician had required sex in return for the procedure. MACS offered information, connected women with sympathetic physicians, and facilitated connections for women seeking abortions, often referring them to the Janes in Chicago.

Now, Arcana is in her 70s, and once again abortion is illegal in fourteen states with total bans. In 26 states and two territories, abortions are legal until fetal viability — the ability of the fetus to survive outside the womb. In the remaining states, abortion is a protected right or protected with some restrictions. At 25 weeks, a fetus has a 67 to 76 percent survival rate.

Despite these state bans, data from the Guttmacher Institute show that abortions in the U.S. increased within the healthcare system from 930,160 in 2020 to an estimated 1,026,690 abortions in 2023, a full year after the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization ended the constitutional right to an abortion. Those statistics include both surgical abortions and those induced via medication in healthcare settings. However, the numbers are presumed to be undercounted because they do not include medication abortions performed at home or abortions obtained outside the healthcare system.

Back in the 1970s, the Janes faced no protesters outside their apartments. The police generally left them alone so long as they safely performed abortions. “We were just ordinary people doing extraordinary things,” Arcana said. Even now, the Janes’ legacy continues in an array of sophisticated, open networks throughout the U.S. to aid women seeking abortions.

Indiana’s law creates confusion

In a state with approximately 1.5 million women of reproductive age, Indiana’s response to Dobbs was to be the first state to enact an abortion ban, Senate Bill 1, at conception, with exceptions. The current exceptions allow an abortion

- to prevent any serious health risk to the pregnant woman or to save the pregnant woman’s life

- if there is a lethal fetal anomaly up to 20 weeks post-fertilization

- in cases of rape or incest, but only up to 10 weeks.

Indiana also limits abortions, including medication abortions, to hospitals and surgical centers owned by hospitals and specifically bans abortion clinics. The language of SB 1 does not impose legal penalties on women seeking an abortion or who get an abortion, and they can still obtain abortion medications by mail in Indiana. Whether women using medication abortion pills for an abortion can be criminally prosecuted remains an undecided legal question.

However, healthcare providers face up to Level 5 felony with one to six years in prison and a fine of $10,000 if they provide an illegal abortion. Currently, Indiana has only two reproductive health/abortion centers, one at Riley Children’s Hospital and the other at Eskenazi Health, both in Indianapolis.

The most persistent question to date has been determining when a fetus is a person, thus giving rise to multiple “personhood” bills in various state legislatures. In the 2024 Indiana General Assembly, two so-called personhood bills, SB 98 and HB 1379, were considered, and both died in the session.

Personhood bills seek to define conception as the beginning of life for a fetus, even though the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ long-established view of pregnancy has been that pregnancy is not established until the fertilized egg is fully implanted into a uterus, an act that can take several days. It’s confusing, said Stephanie Boys, an associate professor of social work at Indiana University Indianapolis and an adjunct professor at the Robert H. McKinney School of Law.

Stephanie Boys is an associate professor of social work and adjunct professor of law at Indiana University. | Courtesy photo

Still, most women do not know that they are pregnant until five and a half weeks after their last period. “So the language in Indiana’s abortion ban is not congruent with medical terminology,” said Boys.

According to Boys, when the Indiana ban was first introduced, it relied on a pregnancy definition beginning at implantation.

“As the bill went through the legislative process and was amended,” said Boys, “the definition of pregnancy was removed and replaced with the state’s definition where life begins at conception.” So under Indiana’s exceptions for rape, a ten-week post-fertilization ban is really twelve weeks of a medical pregnancy. By changing the definition of pregnancy, lawmakers have created this uncertainty, said Boys, and in turn, have confused Hoosiers as well as jeopardized their lives.

The definition also complicates matters in terms of contraception, like Plan B and IUDs, which many people mistakenly believe can end a pregnancy. Plan B does not cause an abortion. It stops the release of the egg from a woman’s ovary and prevents pregnancy. The same is true of IUDs.

The language is also problematic for providers of in vitro fertilization (IVF), said Boys. Alabama’s Supreme Court caused a furor in February when it ruled that frozen embryos created through IVF were considered children, allowing a wrongful death lawsuit for the destruction of the embryos.

Indiana legislators not listening to constituents

The Guttmacher Institute reported that abortion opponents have long sought to promote the definition of life beginning at conception as a reason to ban contraceptives that prevent implantation. The right to such contraception is currently being debated in some states, and even at the federal level. In June, the Senate blocked the Right to Contraception Act, which would have prohibited states from preventing access to contraception. The legislation was blocked by Republicans, including Indiana’s Todd Young and Mike Braun.

In response to the proposed act, Iowa Republicans Sen. Joni Ernst and Rep. Ashley Hinson introduced companion bills to the Senate and House that they say make some contraceptives easier for women to get over the counter. Those contraceptives exclude Plan B and IUDs.

While a constitutional right to contraception still exists, and 14 states protect the right to contraception, Indiana has created no such legal protection.

Haley Bougher is the Indiana director of Planned Parenthood Alliance Advocates. | Courtesy photo

Overall, Indiana legislation on abortion is, according to Haley Bougher, Indiana director of Planned Parenthood Alliance Advocates, an “uphill battle.” Many legislators, said Bougher, represent only their personal, often religious, views, and refuse to hear constituents.

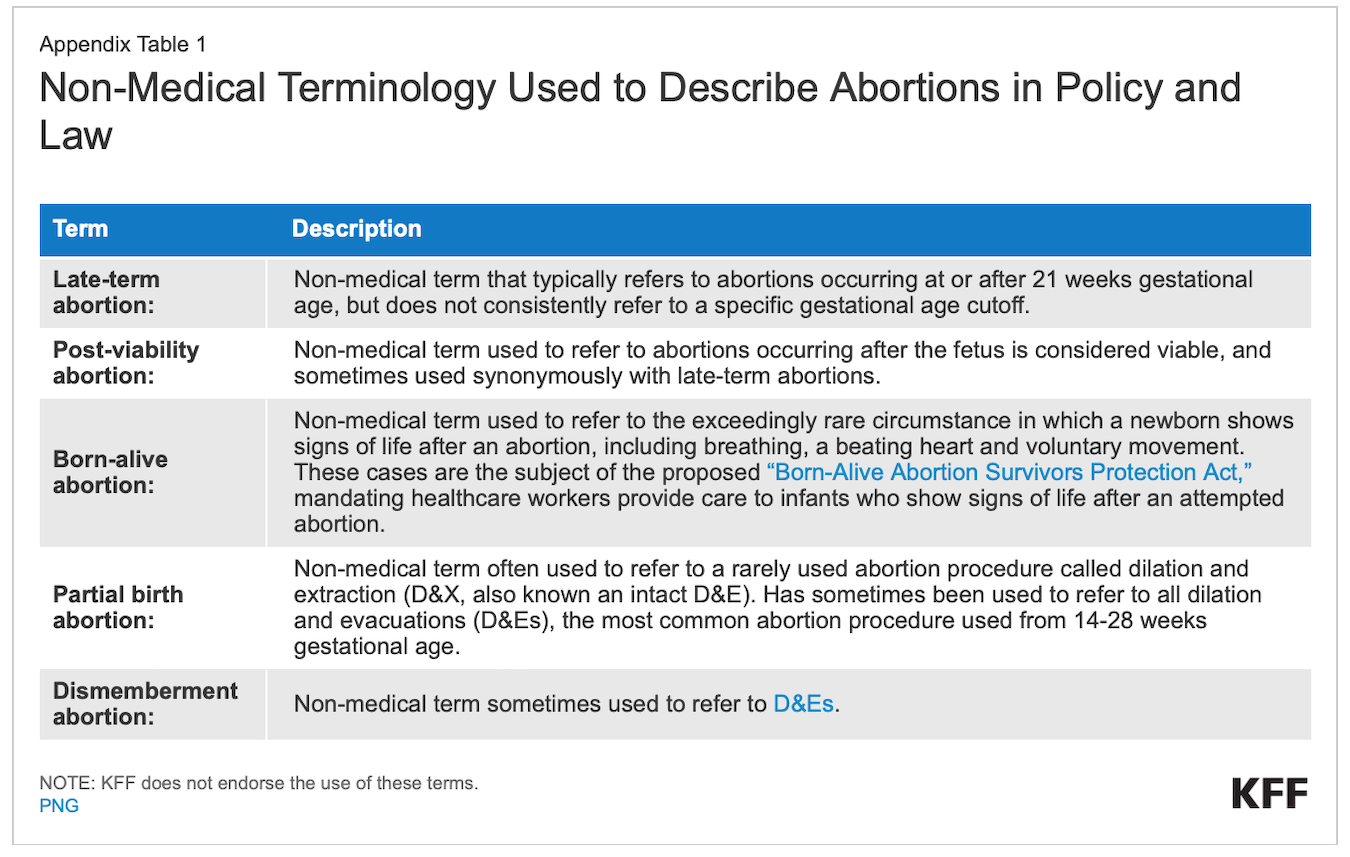

According to historian Mary Ziegler in her new book, Roe: The History of a National Obsession, this has long been true, although now some politicians and advocates also see it as politically expedient to be anti-abortion.

Still, Republican-dominated Indiana continues to dig in on abortion despite Hoosier opinions on the subject. “I cannot believe that we cannot make progress enough to change our state,” said Bougher. “This is not what Hoosiers want.”

She’s right. According to a poll released in May by Our Choice Coalition, an abortion-rights political action group, 64 percent of those Hoosiers surveyed believe that abortion should be legal in all or most cases, and 58 percent believe that Indiana’s SB 1 was too restrictive.

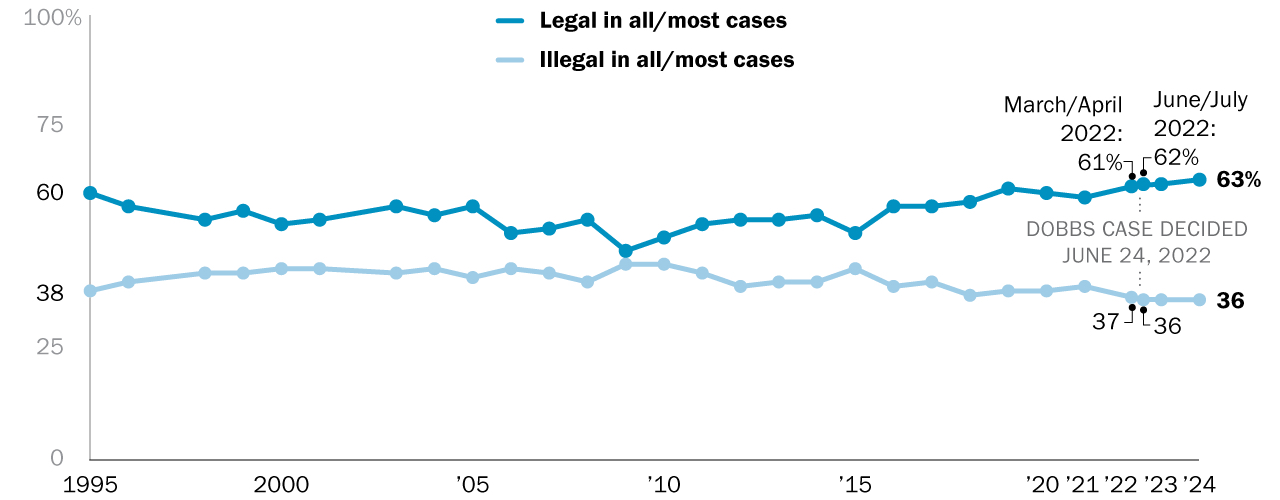

In line with those opinions, a 2023 Hoosier Survey by the Bowen Center for Public Affairs at Ball State University found 59 percent of Hoosiers think abortion should be legal in all or most cases. Nationally, a Pew Research Center study found that 63 percent of U.S. adults wanted abortion to be legal in all or most cases.

Still, according to Bougher, most Indiana legislators are not asking their constituents what they want when it comes to abortion. “They’re not listening to them,” she said. Legislators’ views are more ideological, Bougher said, and since Indiana does not have a ballot measure that allows an issue or question to be placed on election ballots and decided on by voters, restoring access is difficult.

Public opinion on abortion, 1995-2024, Pew Research Center

Percentages of U.S. adults who say abortion should be legal/illegal in all or most cases. | Source: Pew Research Center

According to Ballotpedia, potential abortion-related ballot measures in 2024 include Montana, Nebraska, Missouri, Arkansas, Arizona, and Nevada. Confirmed ballot measures include Colorado, South Dakota, New York, Florida, and Maryland.

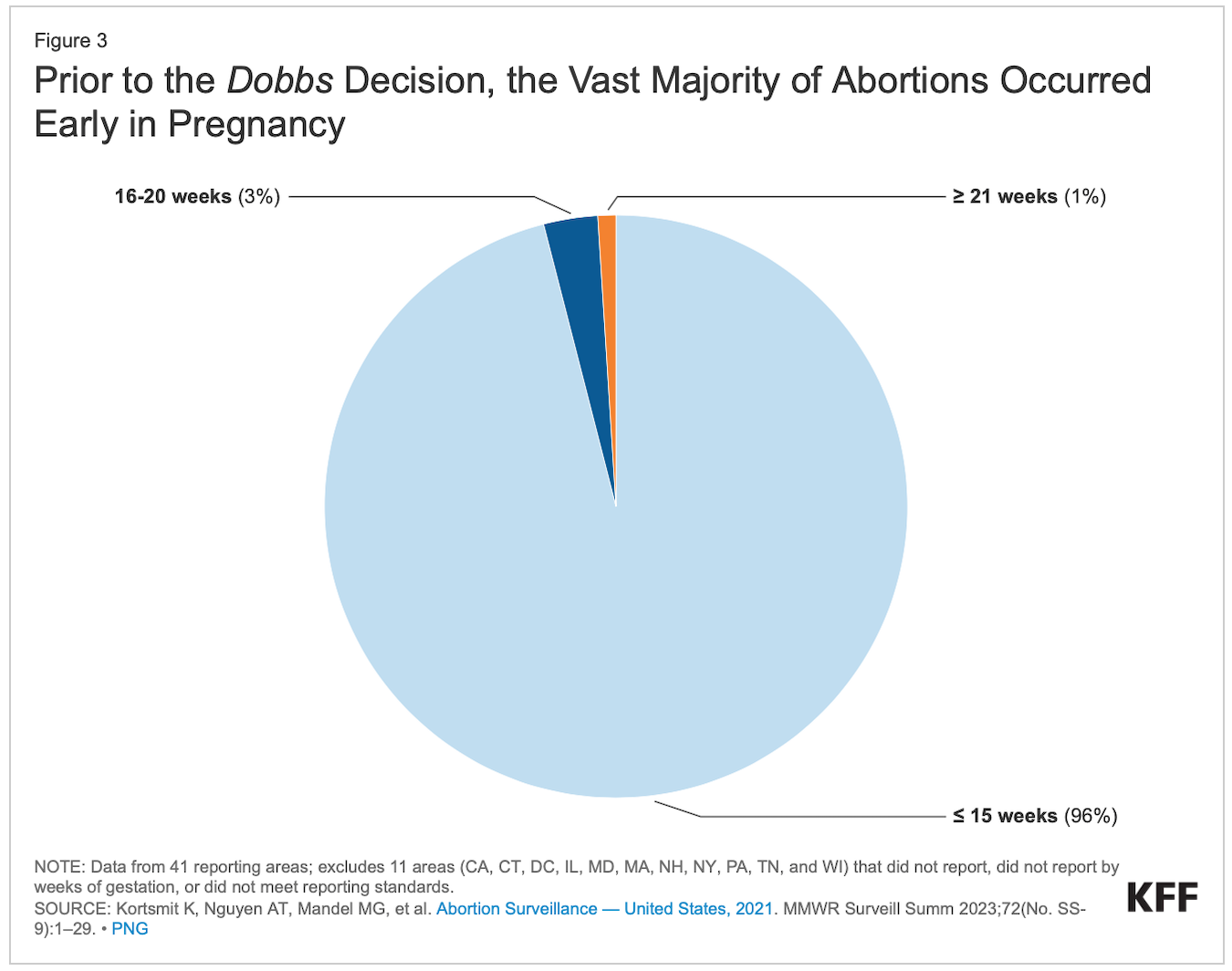

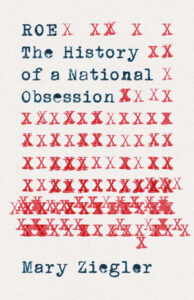

The Midwest networks

In Indiana and the 13 other states with abortion bans, women must find abortion care outside their own health systems. Disinformation and misinformation abound, and women seeking an abortion often do not know what resources are available and how to access them. According to the New England Journal of Medicine, the majority of abortions occur at or before nine weeks of gestation, and more than half of those who get abortions are in their 20s. A recent report by the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) found that only 1 percent of abortions are performed at or after 21 weeks. As a result, women are needing and using abortion network services early in a pregnancy rather than later, as some news media often falsely state.

Source: KFF.org

National and regional networks are now creating access options — for women who can afford it and those who cannot. These options include medication abortion access and funding for accommodation and travel, as well as abortion funding through the 100 abortion funds nationwide, all with security and encryption capabilities to protect patient records from state intrusion.

Overall, according to the National Network for Abortion Funds, such resources have financially supported more than 102,000 people seeking abortions post-Dobbs. The largest fund is the Women’s Reproductive Rights Assistance Project (WRRAP), which was founded in 1991. In March 2024, Guttmacher Institute found that 92,580 pregnant people traveled to a state without total bans for an abortion.

In Indiana, the All-Options Pregnancy Resource Center operates the Hoosier Abortion Fund, which provides funds to people seeking an abortion. Its annual revenue as of 2022 was about $2 million. It also collaborates with the Chicago Abortion Fund, which in 2023 reported $5.2 million in revenue.

After the 2022 Dobbs decision, the Hoosier Abortion Fund received many “rage donations,” and it funded approximately $700,0000 to those seeking an abortion, said State Program Manager Forest Beeley, MPH, but that money has since dried up, as it has in other abortion funds.

Currently, the fund gets an average of 150 calls and gives out an average of $25,000 per month, providing grants ranging from $100 to $300 per case, said Beeley. “We fund anyone living in Indiana who is trying to access abortion care.”

Even though Beeley is not sure if people even realize that they can still get abortions or that there are resources who can help, she wants to make sure they know their current options.

Regionally, the Midwest Access Coalition helps pregnant people who must travel within the Midwest for an abortion. It will fund transportation, lodging, childcare, and even air flights.

Marie Khan, director of programs for the Midwest Access Coalition. | Courtesy photo

Director of programs Marie Khan often fields telephone calls from women throughout the Midwest. Khan works with abortion seekers if they are within ten days of their abortion clinic appointment. She books travel to the city and a hotel, schedules ground transportation, and even provides a volunteer for support. “We have volunteers trained in different city hubs like Chicago,” she said.

According to Khan, 1,795 clients in 2023 received funding, 183 of whom were from Indiana. This year, 114 clients have come from Indiana.

Traveling to a different state for an abortion raises the issue of regulating interstate travel. But trying to ban interstate travel is legally tricky. The right to travel state to state was upheld by the Supreme Court in a 1987 case, Crandall v. State of Nevada, and then upheld again in 1999. However, states like Alabama and Missouri have tried to make it illegal for someone to assist a resident in obtaining an out-of-state abortion by leaving the restrictive state.

Two counties and two cities in Texas passed local ordinances to prevent travel. Idaho became the first state to make it a felony to assist a minor in traveling across state lines for abortion. Recently, in Texas, a man sued three women for $1 million each for helping his wife travel to get an abortion, alleging wrongful death because of the pregnancy termination. Indiana has yet to address this issue.

The U.S. Department of Justice last year expressed interest in protecting the right to travel across state lines for an abortion. However, while there is a fundamental right to interstate travel, whether that includes traveling to another state to get an abortion has not yet been recognized by the U.S. Supreme Court as a basic right under the U.S. Constitution.

“

The language in Indiana’s abortion ban is not congruent with medical terminology.

”

—Stephanie Boys

Bloomington options

Indiana legislators were the first to enact an abortion ban after the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in “Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization” ended the constitutional right to an abortion. | Photo by Limestone Post

In Bloomington, former Mayor John Hamilton’s administration issued a statement in 2022 regarding Indiana’s restrictive abortion ban, saying SB 1 was “passed by the extremist male-dominated General Assembly and signed by Governor Holcomb, which means Hoosier women and those capable of pregnancy are not respected and protected as full and equal residents.” Administrations in other cities also acted to blunt the impact of Dobbs.

Under Hamilton, Bloomington city government made $100,000 in emergency reproductive grants available to nonprofit organizations to support emergency services such as transportation, counseling, post-op exams, medication, and emergency contraception.

All-Options Pregnancy Resource Center received a $15,000 grant that covered travel for abortion care. According to Marissa Parr-Scott of the city’s Community and Family Resources Department, money is still available under the grant, which will be reviewed as the city enters its 2025 budget preparations later this year.

Justin Crossley, digital brand manager in the Office of the Mayor, said he anticipates the grant will continue.

“Mayor [Kerry] Thomson has been a lifelong fighter for women’s reproductive freedom and continues to be an outspoken advocate for those rights today,” Crossley said in an email.

The city’s $248 million budget for 2024 allowed out-of-state reproductive health care for city employees.

Because of the Indiana abortion ban, people in Bloomington and the rest of the state seeking an abortion are now traveling to Illinois, Ohio, or Michigan, all states where abortion is legal until fetal viability.

“My only options as of now is probably either going to Illinois or Michigan to get an abortion if I do become pregnant at some point as a student,” said Donya, a 20-year-old IU student. She’s not alone in thinking this.

The closest clinic to Bloomington is the Equity Clinic, a surgical abortion clinic in Champaign, Illinois. About 70 percent of its caseload comes from Indiana, said Sheryl Rich, executive director. The clinic provides surgical abortions for up to 23 weeks and medication abortions for up to 10 weeks. “We also see patients from Missouri, Iowa, and southern states such as Mississippi, Alabama, and Texas,” said Rich. “About 90 percent of the women who come to us are rural and minority women.”

Source: KFF.org

Choices still available to Hoosiers

Right now in Indiana, women can still travel out of state for an abortion and access medication abortion pills for an at-home abortion because the ban does not penalize those women who travel or take abortion pills. Indiana has not specifically banned either action by law.

Emergency contraception is still available in Indiana despite bans in nine states, although, Boys said, Indiana legislators “have left the door open to banning Plan B.” Women also can get a tubal ligation or their partners can get a vasectomy, both of which can be reversed.

According to a 2024 research letter in JAMA Health Forum, early research documented a rise in birth control, including tubal ligations and vasectomies, after Dobbs. The authors wrote that while the study did not confirm that Dobbs caused the increase, it did find that tubal ligations increased twice as much as vasectomies, an increase of 58 more tubal ligations per 100,000 outpatient visits and 27 more vasectomies per 100,000 outpatient visits.

On Valentine’s Day 2024, Planned Parenthood nationwide began offering vasectomies to patients.

“We are hearing that many people do not want to risk becoming pregnant in southern Indiana,” said Bougher, the Indiana director of Planned Parenthood Alliance Advocates.

Jennifer (not her real name) is one of those women who opted for a tubal ligation. She and her partner do not want children. While she did not get the ligation in anticipation of Indiana’s abortion restrictions, she had her surgery one month before SB 1 was passed.

“I was afraid that if I hadn’t gone through with the surgery, or my birth control became ineffective, I would be in the situation that I wouldn’t want to be in,” she said. “I did think about the consequences, but in the end, I am glad my physician recommended me to a surgeon who would do the procedure. I don’t have any fear now of unwanted pregnancy and the fear of what would happen if I were in that situation. It’s almost a relief.”

Jennifer is not alone in making plans to avoid pregnancy. When the Indiana ban came into effect, Samantha (not her real name) and her sister crafted a survival plan in case one of them needed an abortion. They decided that they would travel to one of their siblings’ states where abortion restrictions were not so draconian. And since birth control is not 100 percent failsafe, they created a plan for funding abortion, a cost that can be anywhere from $600 to $2,000, not including travel, food, and other necessities, according to Planned Parenthood.

“Most girls my age I know have something similar or an emergency fund for ‘just in case,’” said Samantha, a college-aged student. “I no longer get to choose how I want to handle my reproductive health for purposes other than birth control because I am so afraid of having to reap the consequences of an accidental pregnancy.”

59 percent of Hoosiers either think abortion should be legal in all or most cases.

—2023 Hoosier Survey by the Bowen Center for Public Affairs at Ball State University

Medication abortions

Guttmacher Institute’s Monthly Abortion Provision Study found that more than 63 percent of all abortions are done via medication, up from 53 percent in 2020. First approved in 2000 by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), medication abortion pills mifepristone and misoprostol are considered safe and effective methods for an abortion.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the FDA allowed for telehealth visits with physicians. In 2023, it changed regulations again to allow for healthcare providers and online pharmacies to mail the drug to those seeking abortions. Since then, organizations like Plan C, Just the Pill, AID Access, and others have supplied these medications via U.S. mail and have been providing telehealth medication abortions.

The pills work like this. Mifepristone blocks progesterone that is needed for a pregnancy to continue. The second step is taking misoprostol. It, in essence, empties a pregnant person’s uterus like an early miscarriage, causing cramping and some bleeding. It also can cause nausea, diarrhea, headache, dizziness, fever, and chills. It can be taken 48 hours after the mifepristone or when a doctor advises. Lastly, to ensure that the uterus is completely emptied, a pregnant person should visit their healthcare provider or take a pregnancy test to be sure.

To access medication abortion pills up until the 13th week of pregnancy, like through AID Access, a pregnant person calls a toll-free phone number or goes to the website and fills out a consultation form to set up a consultation with a healthcare practitioner.

Despite the side effects of the drugs, numerous studies have demonstrated the safety of the procedure. The New York Times reviewed 101 scientific studies, concluding that medication abortion is safe. And a study published in the journal Nature Medicine found in a survey covering 20 states between April 2021 and January 2022 — a total of 6,034 abortions — that 97.7 percent of the abortions completed with mifepristone and misoprostol were performed without any subsequent medical intervention. Overall, 99.8 percent of those abortions did not incur any adverse effects.

Lauren Jacobsen is a registered nurse practitioner with Raise Global Health and AID Access. | Courtesy photo

Lauren Jacobsen, a registered nurse practitioner with Raise Global Health and AID Access, has been practicing for seven years. As a healthcare professional, she operates remotely and is protected by a shield law in her state. A shield law protects practitioners from extradition, loss of licensing, and prosecution. Washington, Massachusetts, Colorado, New York, and Vermont currently have shield laws. According to Jacobsen, AID Access has about ten providers in different U.S. shield states.

Because of the shield law in her state, Jacobsen can mail abortion pills to pregnant persons in other states like Indiana without facing prosecution. “In the last few months, I alone have been sending about one thousand packages to people,” said Jacobsen. “About half of our shipments are going to Texas right now.”

The pills cost $150, but AID Access offers a sliding scale for those who cannot afford it. In addition, it provides a provisional order option, which means that a person can order pills in anticipation of needing them. According to Jacobsen, AID Access gets about 10 percent or fewer of its orders from Indiana.

According to a JAMA Internal Medicine study on AID Access’s provisional order for September 2021 to April 2023, AID Access received 48,404 requests for advance provision. The requests increased after someone leaked the Dobbs decision to Politico and again after the Dobbs ruling in May 2022 — and again after legal rulings on mifepristone approval. After an eight-month investigation, the origin of the leak was never disclosed.

Anti-abortion activists continue their fight to prohibit access to medication abortion pills. Louisiana recently declared abortion pills to be a controlled substance that needs a doctor’s prescription to access. Other states have attempted to restrict distribution by pharmacies, making it a felony to distribute, prescribe, dispense, sell, or transfer the pills, and banning mail-order pharmacies from distributing the drugs.

“

I no longer get to choose how I want to handle my reproductive health for purposes other than birth control because I am so afraid of having to reap the consequences of an accidental pregnancy.

”

—Indiana resident

Applying a law from 1873

One issue that has arisen with medication abortion is the revival of the 1873 Comstock Act. Named after Anthony Comstock, a 19th-century anti-pornography crusader, the Comstock Act of 1873 prohibits the “obscene, lewd, or lascivious” materials that are “intended for the prevention of contraception or procuring an abortion” being sent through the U.S. Postal Service. The law forbids writings and instruments about contraception and abortion, even if written by a physician.

The U.S. Department of Justice Office of Legal Counsel issued a 2022 opinion on the use of the Comstock Act, stating the mere mailing of these drugs did not establish evidence that a person intended to use them unlawfully.

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito has raised the possibility of applying the 1873 Comstock Act to medication abortions. | Photo by Josh Ellie, CC-BY-SA-4.0

However, a recent U.S. Supreme Court hearing hinted at another use for the Comstock Act. In May, the court heard arguments on the Food and Drug Administration v. Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine, which challenged whether the Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine had standing to challenge the 2016 and 2021 actions regarding the approved use of mifepristone. In the hearing, justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito (at 1:13:30) both queried the application of the Comstock Act to the question posed in the case, raising publicly for the first time the possible application of the 1873 law to medication abortions.

On June 13, 2024, the Supreme Court ruled unanimously that the Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine had failed to show injury and therefore lacked standing to bring a case against medication abortion pills. This ruling restored continued availability of mifepristone under current FDA rules.

In addition, the use of the Comstock Act to prevent medication abortion has arisen in Project 2025, a blueprint by the Heritage Foundation and other conservative groups, which they call Mandate for Leadership, if Donald Trump prevails in the November 2024 election. It expressly states, “Allowing mail-order abortions is a gift to the abortion industry that allows it to expand far beyond brick-and-mortar clinics and into pro-life states that are trying to protect women, girls, and unborn children from abortion.”

Historian Mary Ziegler’s new book, “Roe: The History of a National Obsession”

Further regarding the Comstock Act, Project 2025 mandates to “stop promoting or approving mail-order abortions in violation of long-standing federal laws that prohibit the mailing and interstate carriage of abortion drugs,” thus laying the groundwork for what may come after the 2024 election. In a recent draft of an article for Yale Law Review, Mary Ziegler writes that the anti-abortion movement sees using Comstock to create a “de facto national ban on abortion.”

When asked what AID Access would do if action was taken to ban mailing and distribution under Comstock, Jacobsen replied, “We’ve played out a lot of scenarios, and we have backup plans to our backup plans. So we will continue to provide mifepristone and misoprostol to those needing them in all fifty states. We’re a few steps ahead with our planning.”

The outcome of the general election in November will impact how state legislatures will address abortion and even IVF and contraception. But history has shown that bans do not stop abortions. Today, resources for abortions are more organized and technologically sophisticated. Women have adapted, creating organized systems that support women who want an abortion. And like the Janes, they will go underground if necessary. Despite the persistence of conservative legislators and their religious activists seeking to marginalize women’s reproductive health, women have “backup plans to our backup plans,” as Jacobsen said. Abortions didn’t stop before, and they won’t stop now.

[Editor’s note: Some sources requested use of only their first names out of concern for their privacy and safety.]

Read: Part 2 of this series, “The Harmful Consequences of Indiana’s Badly Written Abortion Ban,” by Rebecca Hill

Abortion and Religious Freedom in Indiana

In April 2024, the Indiana Appeals Court ruled in Individual Members of the Medical Licensing Board of Indiana v. Anonymous Plaintiff 1 that Indiana’s abortion law interfered with the plaintiffs’ right to religious freedom. The plaintiffs, Hoosier Jews for Choice and four women, argued that Indiana’s restrictive abortion ban hampered their ability to exercise their religion in violation of the state’s Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA), passed in 2015 under Gov. Mike Pence’s administration. Under RFRA, Indiana must show a compelling state interest before forcing someone to do something against their religion.

Initially, the act arose over a case of LGBT discrimination and a business refusing to serve LGBT patrons. In the Hoosier Jews for Choice case, plaintiffs argued that Senate Bill 1, which created an abortion ban at conception (with exceptions), violated Jewish law, which encourages and allows abortion to save the life of the pregnant mother. The Indiana appeals court ruled for Hoosier Jews for Choice, saying that Indiana’s restrictive abortion ban exceptions based on health demonstrated that the state recognized secular grounds for prioritizing the health of the mother and, therefore, denying the plaintiff’s case meant that the state was “effectively discriminating against religion.” A preliminary injunction was granted and the Indiana State Appeals Court affirmed it on April 4, 2024. To date, this case has not been filed with the Indiana Supreme Court.

The Bloomington Health Foundation is an underwriting partner of Limestone Post. As the local philanthropic expert for improving community health for more than 50 years, Bloomington Health Foundation is expanding its mission to address the most pressing health needs in Bloomington and neighboring communities.

The Bloomington Health Foundation is an underwriting partner of Limestone Post. As the local philanthropic expert for improving community health for more than 50 years, Bloomington Health Foundation is expanding its mission to address the most pressing health needs in Bloomington and neighboring communities.