Despite living through years of hardship under the French, the Americans and their Vietnamese allies, and, more recently, conflicts with China, a vendor in a market in the coastal city of Hoi An has a ready smile for customers. She wears the nón lá — a conical hat made of palm leaf and worn by Vietnamese of all ages and both genders. | © Steve Raymer / National Geographic Creative

Looking for an engaging evening? Let me suggest a pleasant conversation over a glass of Beaujolais with Steve Raymer, veteran National Geographic photographer and Indiana University emeritus professor. An affable raconteur who’s been everywhere — literally — and, if not done everything, has experienced enough action to fuel three or four adventure novels.

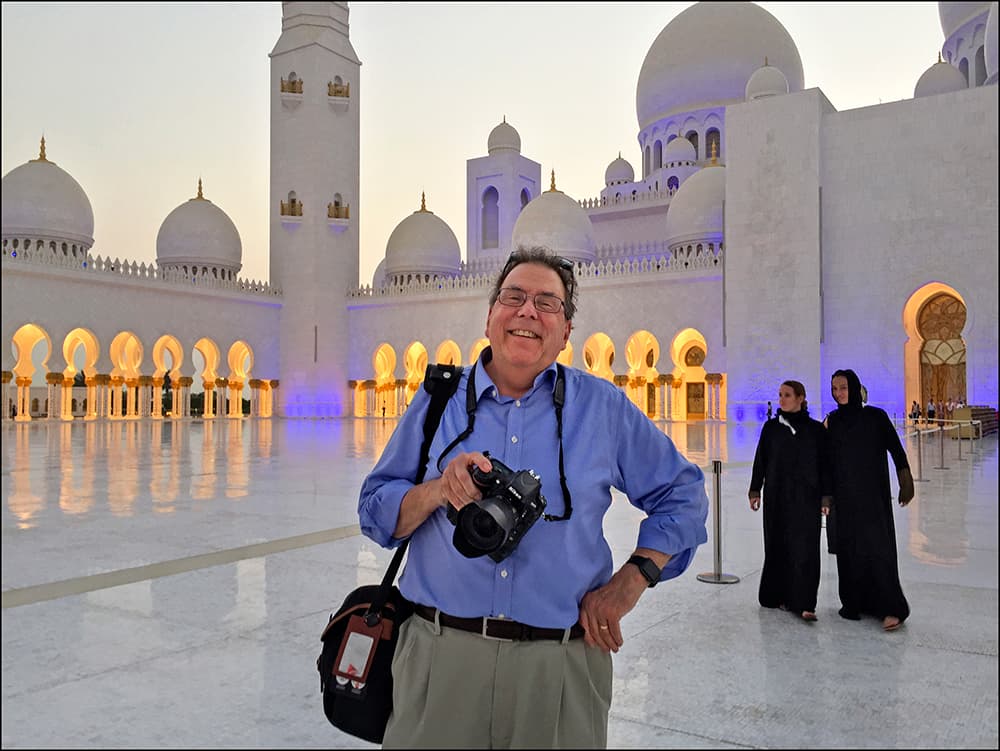

Photojournalist and professor Steve Raymer at the Sheikh Zayed Grand Mosque in Abu Dhabi, one of the world’s largest mosques that can accommodate more than forty thousand worshippers. In 2017, the mosque was ceremonially renamed after the mother of Jesus Christ — Mariam, Umm Eisa, Arabic for “Mary, the mother of Jesus.” Sheikh Mohammed Bin Zayed Al Nahyan, crown prince of Abu Dhabi, says he ordered the change to build bridges to other religions. | Photo courtesy of Steve Raymer

As his Grand Pyrenees, Sophie, nuzzles your knee, Raymer could regale you with stories about catching shrapnel in his back during Pol Pot’s takeover of Cambodia, photographing Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi shortly before her bodyguards assassinated her, being among the first to reach the Chernobyl plant after its nuclear meltdown, or fording a river laced with land mines in El Salvador.

Instead of war stories, though, what he really wants to talk about are ideas, ethics, history, change, and, especially, the crucial role photojournalists play as witnesses to the world’s beauty and horrors.

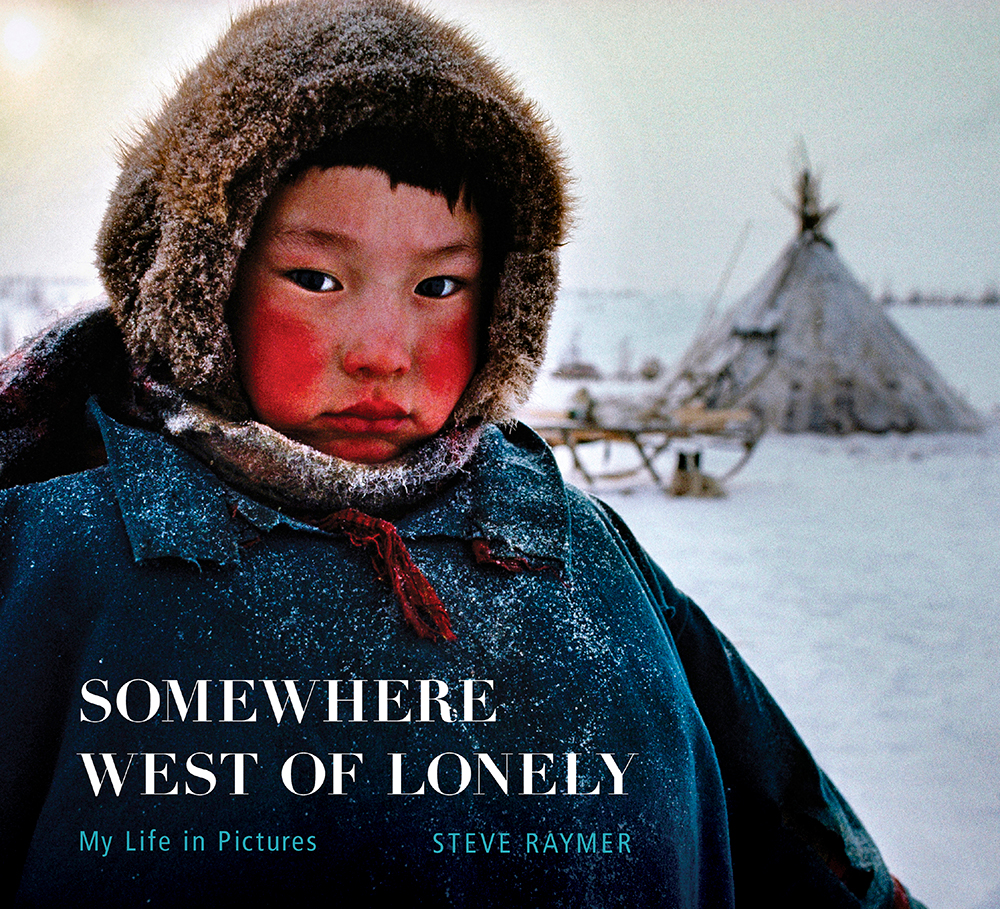

If you cannot join Steve in person, you’re welcome to eavesdrop on my chat with him. Better yet, let me suggest his latest book, Somewhere West of Lonely: My Life in Pictures, just published by Indiana University Press.

In 150 photographs, many never before published, the book traces the path of a young newspaper photographer from Wisconsin — who had never taken a color photograph when he was hired at National Geographic in 1972 — through his first career of photographing magazine picture stories and his second of producing photography books while teaching at IU.

You’ll find a few news pictures: an elderly man flying the flag upside down as he protests the Vietnam War at Richard Nixon’s second inauguration, a smoldering Mount St. Helens after its 1980 eruption, or be-medaled Soviet generals in 1990 celebrating World War II victories. But monthly magazines like National Geographic don’t trade in spot news, and Raymer’s pictures aim for meaning that lasts beyond yesterday’s headlines.

The cover of Raymer’s book “Somewhere West of Lonely.” At home above the Arctic Circle, this Nentsy boy and his family live in a chum, a tepee-like shelter made of reindeer hide. Soviet officials tried to organize the nomadic Nentsy into collectivized farms, but the Nentsy of the Yamal Peninsula — a region of oil and natural gas riches where winter temperatures can plummet to minus 58 degrees Fahrenheit — continue to migrate with their herds more than 600 miles each year. | © Steve Raymer / National Geographic Creative

He acknowledges the criticism that Geographic photographers sometimes objectified their subjects in pursuit of the exotic and admits taking a few such pictures himself. But he believes the tourism industry has changed that. “There aren’t that many exotic places left in the world,” he says. “Today, everybody goes to these places.” Now, the challenge is to promote understanding. “Our job is to make the everyday interesting and informative to readers,” he says. “To find the intimate moment in an everyday situation.”

Intimacy abounds in several of the book’s photographs that celebrate the human face in its myriad iterations. Raymer seeks to look “into the eyes of people and have them reveal something of themselves, their lives. Most of the time you can’t speak their language, but that eye contact can draw the reader in.”

As an example, he points to a close-up of a Vietnamese market vendor whose wide smile lights up her wrinkled face. As Raymer chatted with her, they established a bond that he was able to capture and share.

The book teems with the images you remember from well-thumbed Geographics: rickshaw wallahs waiting for fares in Calcutta, renamed Kolkata in 2001; hula dancers on the rim of a 3,000-foot-deep canyon on Kauai Island; white-haired men in yarmulkes and prayer shawls reading the Torah at a Moscow synagogue; Thai women harvesting rice knee-deep in a muddy paddy; and a Bedouin hugging his camel’s neck. Some, such as two women in burqas walking past a Britney Spears cosmetic ad in a Dubai shopping mall, capture the clash of cultures that complicates our shrinking world.

Whatever their ostensible subject matter, Raymer’s photographs are always about color and the light that makes it magical: from yellow gas flares barely making a dent in the deep purple sky over Prudhoe Bay, Alaska, to three children on a Seychelles beach silhouetted against a flaming red-orange sunset to the book’s cover photograph of a Nentsy boy, his cheeks stained a deep magenta by temperatures that reach a minus 58 degrees Fahrenheit at his home north of the Arctic Circle.

Transplanting rice seedlings is backbreaking work for Thai farmers, who in 2016–17 produced an estimated eighteen million metric tons of long-grain Jasmine rice. The world’s largest producer of rice, Thailand harvests two crops a year in the wet and dry seasons. | © Steve Raymer / National Geographic Creative

In a book full of fascinating, often beautiful, photographs, perhaps the most telling image is the introductory map that marks the locations in more than 100 countries from which Raymer reported.

With so many captivating photos, you might be tempted to overlook the text. Don’t make that mistake. Raymer is an engaging writer. He telegraphs situations, circles back around, drops in reminders, and keeps his narrative lean. A natural storyteller, he interweaves his first-person account with recent world history and an honest engagement with the philosophical ideas and ethical issues swirling through the practice of photojournalism. Having taught photojournalism and media ethics at IU for more than two decades, he is ideally positioned to parse concerns from invasion of privacy or getting personally involved in a story to the accusation that war photographers are addicted to the adrenalin resulting from combat.

Ration card clutched in her left hand, a mother waits with her three hungry children for powdered milk donated by the United States and Canada and dispensed by the Dutch Red Cross — another mind-numbing scene in Bangladesh during the 1974 famine. International relief experts called Bangladesh the most underfed and overcrowded nation in the world, while The New York Times reported, “Mass hunger and starvation is no longer a threat. It is here.” | © Steve Raymer / National Geographic Creative

His insider’s account of how magazine photojournalism has changed in 45 years is especially revelatory. In an age where everybody has a camera in her phone and trillions of images get made, and forgotten, each year, Raymer represents an era unfathomable to many — when producing a memorable photo required access and advanced planning, communication was limited to terse cable dispatches, and logistics demanded ingenuity. He recalls shipping film back to Geographic’s home office in Washington, D.C., and waiting, often for a month or more, for an editor to critique his take.

His images remind us that, however easy it is to click a cellphone shutter, apply an Instagram filter or Photoshop a background, a great gulf exists between our pictures and those of professionals who devote their lives to capturing the revealing moments that celebrate our shared humanity.

Engulfed in opium smoke, an addict of the Lisu ethnic hill tribe mixes a pipe of the narcotic in a village in the Golden Triangle of Southeast Asia, where Thailand, Laos, and Myanmar meet. The Golden Triangle was the largest supplier of opium in the world, but the region has since been eclipsed by the Golden Crescent — the poppy-growing area in and around Afghanistan. | © Steve Raymer / National Geographic Creative

That gulf transcends the technical to encompass essential purposes. As Raymer writes in his dedication, photojournalists provide the essential eyes for citizens in democratic societies to understand an increasingly complex world. They endure danger, hardship, emotional stress — and in some cases sacrifice their lives — to bear witness to the beauties and horrors of our conflicted planet. They take an unblinking look at situations when many of us would avert our eyes.

The book’s title refers to an actual place, Lonely, Alaska, where Raymer and his writer colleague, Bryan Hodgson, barely escaped a helicopter crash during a whiteout. When Hodgson’s phrase “somewhere west of lonely” got cut by a Geographic editor, they commiserated over wine, and Raymer promised him, “Bryan, if you don’t get it published, I will someday.”

But there’s a deeper significance. “Yes, Lonely is a place,” Raymer says, “but it’s also a metaphor for life on the road. You don’t have to go to Lonely, Alaska, to feel lonely. You’re away from your family and home for long periods of time.” On the positive side, he believes solitude can spark creativity. He embraces “being in that isolated situation where you focus all your energies on ‘Why am I here and what am I trying to say?’”

Long before US Naval Station Guantanamo Bay in Cuba became a military prison for suspected terrorists on a slice of land arguably beyond the reach of US constitutional protections, it housed some forty-seven thousand Cuban and Haitian detainees during the 1990s. These refugees were picked up at sea fleeing their homelands for the United States and held in heavily patrolled tent cities ringed with razor wire. | © Steve Raymer / National Geographic Creative

The book found its genesis in his valedictory lecture as a full professor of journalism. He turned his notes into a chapter outline, then wrote the text during the summer of 2016. It joins his five previous books on Vietnam; Saint Petersburg, Russia; the Muslim world of Southeast Asia; the global Indian diaspora; and Kolkata.

And he’s not finished. “I’ve got two books that I want to do, if my knees hold out,” he jokes. He’s in the clean-up stages of a book about the pubs of Great Britain, which are closing at an alarming rate. “I need a good overall photo of London,” he says. “Then I’m going to take a car and go to the west country beyond Oxford, out to the Cotswolds, down to Bristol, maybe out as far as Cornwall. And it’s done!”

West of Lonely has photographs from his pub project, including one of a portly businessman hoisting a pint in Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese, which has purveyed brews to the likes of Charles Dickens, Arthur Conan Doyle, P.G. Wodehouse, and Mark Twain since the Great Fire of London in 1666.

A white-collar crowd mingles with tourists at Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese, which survived the Great Fire of London in 1666. Locals say the pub’s lack of natural lighting generates a gloomy charm, something that appealed to authors such as Charles Dickens, Mark Twain, Alfred Tennyson, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, and G. K. Chesterton, who were all regulars. The pub is alluded to in Dickens’s “A Tale of Two Cities” as a haunt where a gentleman could recoup “his strength with a good plain dinner and good wine.” | © Steve Raymer / National Geographic Creative

The second project will explore the concept of “a favorite place where we feel most at home, most comfortable, and most at peace.” He plans to make environmental portraits of 50 to 100 people, including some famous folks, in their favorite places.

Raymer exemplifies scores of IU faculty members at the top of their fields, who enrich Bloomington. He joined the School of Journalism [now a part of the IU Media School] in 1996, teaching courses for 20 years in photojournalism, visual communication, international reporting, and the history of reporting war and terrorism. In retirement, he regularly teaches a course on media ethics and values, required of all journalism majors. Circumstances change its contents each semester, but Raymer begins with a bedrock principle of western civilization. On the first day of class, he challenges students with an image of the Hippocratic oath to do no harm — shown in the original Greek.

Menacing cumulus clouds are mirrored in the placid waters of Lake Murray, the largest lake in Papua New Guinea, covering an area of some seven hundred square miles. About five thousand indigenous communities inhabit this lake region. In 1923, The New York Times reported on an Australian expedition that used amphibious airplanes to chart Lake Murray and the explorers’ close encounters with indigenous people called, at the time, “head-hunters.” | © Steve Raymer / National Geographic Creative

With a bachelor’s and a master’s degree from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, he served as a lieutenant in the United States Army, pulling a tour in Vietnam. After joining the staff of National Geographic in 1972, he produced more than 30 bylined articles in 24 years. He received a coveted mid-career John S. Knight Journalism Fellowship at Stanford University to study Soviet and Russian affairs. With help from his wife, Barbara Skinner, a professor of Russian history and fluent Russian speaker, he produced Geographic stories in 1990, 1991, and 1993 on Russia as it emerged from the disintegration of the Soviet Union.

You probably know about the Pulitzer Prize, but most photojournalists place a higher value on the peer recognition that comes from the annual Pictures of the Year competition. POY named Raymer “Magazine Photographer of the Year” for his 1976 reporting on the global hunger crisis. The Overseas Press Club of America cited him for excellence in foreign reporting. The National Press Photographers Association and the White House News Photographers’ Association have given him numerous first-place awards.

Shouting “traitor,” a flag-waving colonel of the Soviet Army confronts a pro-democracy demonstrator at a May Day parade on Red Square in 1990. Hundreds of thousands of Soviet citizens turned a working-class holiday into an angry display of popular discontent with communist rule — a movement that would lead to the dissolution of the Soviet Union in December 1991. | © Steve Raymer / National Geographic Creative

His new book has earned him yet another accolade. In early September in Perpignan, France, he will be featured at the World Press Organization’s Visa pour l’image, the premier international festival of photojournalism. His photographs and a voice-over interview will be screened in an ancient Roman amphitheater.

Raymer generously credits colleagues who helped him and journalists who inspired him. Chief among the academic colleagues he thanks is Trevor Brown, former dean of IU’s School of Journalism and his supervisor/mentor. As Raymer made the transition from magazine photojournalism to academe, Brown dubbed him a photo-anthropologist and encouraged him to create long-form photographic books.

Performing the hula kahiko, or ancient Hawaiian hula, dancers blend simple footwork with hand gestures to illustrate the myths and histories of their families on the rim of the Waimea Canyon on Kauai. | © Steve Raymer / National Geographic Creative

Raymer feels lucky his career spanned the “golden age” of magazine photojournalism when he had unlimited time, freedom, and finances to tell a story as he envisioned it. Perhaps it’s his years of being around students, but he believes the new generation represents an even brighter future for photojournalism.

“All these people who say that photojournalism is dead are just plain wrong,” he insists. “There are a lot of photojournalists out there trying to explain the world to us today. They’re young, and they’re smart, and I think they’re more courageous than we were, because they don’t have the backing of major corporations, major media organizations. They are overwhelmingly freelance.” He sees them as risk takers, who are more versatile than his generation, because “they can deliver video and audio as well as still pictures.”

As if in a scene from the early twentieth century, rickshaw-pullers rest on a backstreet in Calcutta, now renamed Kolkata, capital of the Indian state of West Bengal. The city’s some six thousand licensed rickshaw drivers are often called “human horses” and generally earn less than five dollars a day navigating the city’s crowded and sometimes flooded streets. | © Steve Raymer / National Geographic Creative

He points to James Foley, a video reporter who was beheaded by ISIS in Syria in 2014, as probably the best known among this younger cohort. “But there are hundreds of James Foleys out there,” he says. “They are one-woman and one-man bands and they are doing this not because they’re being paid a lot or because anyone even cares, but because they are drawn to the work. I think we need to recognize this is a calling.”

Listening to Raymer’s enthusiasm, you suspect he’s almost ready to join this new generation for another chapter in his career. But first, another glass of Beaujolais.