Ann Barlow died two weeks after Easter this year, as snow was falling like a pox on the barely budded spring. Her daughter Sarah had been trying to reach Ann for hours from her apartment in Bangkok, but when the nonstop ringing persisted throughout the day, she messaged a friend in Nashville to check on her mom’s small, not-quite-finished house located off of State Road 45. Ann’s health and mobility had been declining for the past couple of years, and the weekly call with her daughter halfway around the world was like comfort food, unmissable, something to be stretched and savored for three uh-huh, uh-huh, oh-really, yeah, remember-when hours. It was very unlike Ann to skip this meal.

Ann, pictured here in the 1970s, joined a loose-knit group of free-thinkers who had taken root on roughly 500 acres of land, known as Needmore. | Courtesy photo

She was found in her bedroom. The window, where she could stand and survey the thick curtain of yellowwoods strung across her property, was still open a few inches for the warmer weather that had preceded the snow. Praying it was quick for her, Sarah wrote in an email to her cousin that day. Also know for sure my mom would’ve utterly detested being sick in a hospital bed or in a nursing home. Life has its way of working things out.

Indeed, Ann’s life ended exactly where it was supposed to — in the house she built on the ridgeline of Brown County where her stone had stopped rolling 40 years earlier. She was an artist, craftswoman, forager, seamstress, mechanic, newspaper deliverer, meter reader, waitress, flower vendor. She was also gentle, contrarian, nurturing, outspoken, mercurial, arch, smart. Women like her stomped a wide path through the 1960s and ’70s, and though their hike is far from over, Ann at least got to see a black president and her 69th birthday. She grew up in Indianapolis and lived for a few years in Bloomington, but always wanted a place where she could feel outside even when inside. After the birth of Sarah, she settled 15 miles to the northeast of town, in Needmore (sometimes spelled Kneadmore), joining a loose-knit group of several dozen free-thinkers and windmill-tilters who’d already taken root on roughly 500 acres of land purchased in the late ’60s by Kathy Canada, an heir to the Lilly fortune, and her husband Larry Canada, a charismatic activist.

Needmore wasn’t — and still isn’t — an anomaly in Indiana. The southern half of the state has a rich history of incubating what are now referred to as intentional communities (the word commune can sound like Jonestown to the ear of someone who currently lives, er, intentionally). New Harmony, along the Wabash River near the toe of the state silhouette, is arguably the best known of Indiana’s intentional communities. It was settled around 200 years ago and attracted a mix of idealists and intellectuals, as well as “crackpots, freeloaders, and adventurers whose presence in the town made success unlikely,” according to William E. Wilson’s book The Angel and the Serpent: The Story of New Harmony. After 10 years as a settlement and a mere two years as an incorporated community, New Harmony fell apart — its demise a stark lesson in the fragility, and often futility, of sustaining Utopia.

Members of May Creek Farm celebrate May Day with a maypole. | Courtesy photo

Southern Indiana has at least three long-established intentional communities — all relics of the 1960s and ’70s — that have managed to avoid New Harmony’s fate: Needmore in Brown County, Padanaram in Martin County, and May Creek Farm in Monroe County. If the newspaper clips at the Monroe County Public Library are any indication, Padanaram has always been the exception of the three — and certainly the most newsworthy. Needmore and May Creek Farm were manifestations of the era’s back-to-nature hippie sensibility, but Padanaram was more a case of divine inspiration. Itinerant preacher Daniel Wright launched the community in 1966 after the Lord guided his car to an undeniably heavenly valley within a forest of virgin hardwood, not far from the Crane Naval Surface Warfare Center. Even today, the two-lane road leading from State Road 37 to Padanaram’s turnoff is dotted with small churches and ministries — eight in just 11 miles — a reflection of both the piety and conservatism that have long knitted together this pocket of the state. Needmore and May Creek Farm, by comparison, represent the cross-stitch of intellectualism and progressivism that are characteristic of Bloomington.

Regardless of their foundational differences, all three communities have had to bend with the times in order to survive, by allowing private ownership of land, attracting members who commute to city jobs, and chasing drugs away rather than welcoming them. Their combined 144 years of perseverance are impressive in the paler light of New Harmony’s 144 months, but these communities still face the same existential question that pesters any maturing organization, whether formal, familial, or loose-knit: Who will keep this going after the old guard fades away?

***

Sara Steffey McQueen, right, and her husband, Mike, are founding members of May Creek Farm. | Limestone Post

The words pour out of Sara Steffey McQueen in a torrent of sentence fragments; there’s so much to tell and not enough time for commas, periods, or sometimes even predicates. Her voice rises, falls, trails off as she recalls the early days of May Creek Farm, an intentional community of 26 current members that she helped establish four decades ago, just a few miles outside of Bloomington. Sara, a 67-year-old artist and creativity coach, catches herself and laughs at the multiple tangents of nonlinear history she’s just imparted. “Oh, I could write a book about everything that’s happened.”

Sara, her husband, and half a dozen other community members have gathered for a regular council meeting near their one-acre pond, taking full advantage of the low humidity, dearth of mosquitoes, and a brilliantly setting sun. By her authority as the nominally paid community secretary, Sara begins to lead the discussion. Gone is the loquacious docent, and in her place — a focused facilitator who doesn’t endure long tangents and who firmly pulls the conversation back on track whenever it slips off the rails. There’s a list of things they need to get through during this meeting, and Sara doesn’t have all night.

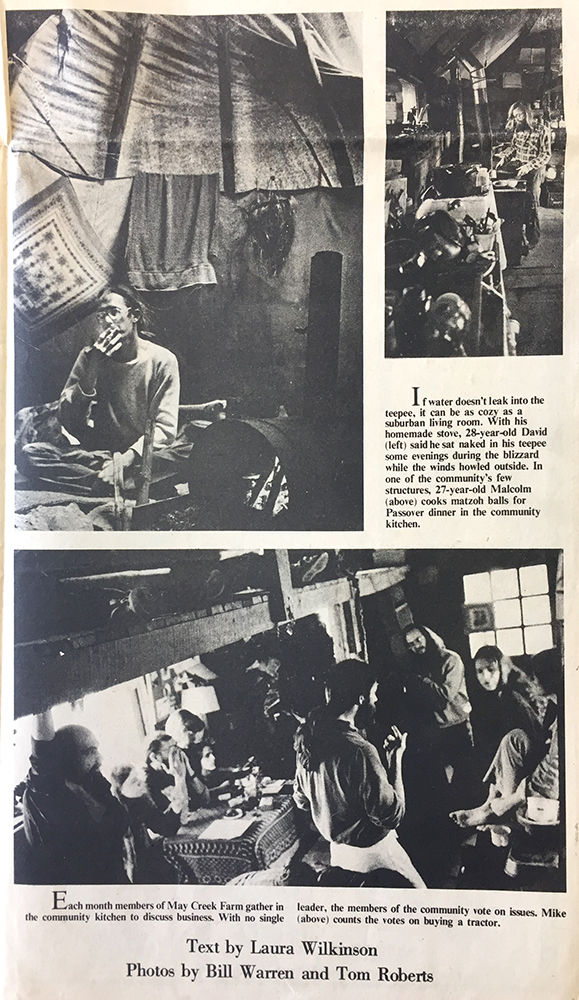

In the 1970s, several publications — from “The Herald-Times” to the “South Central Topics” to “The Courier-Journal & Times Magazine” — reported on “communes” in the area, such as this 1978 photo spread about May Creek Farm in the “Indiana Daily Student.” Click here to see the entire spread and click here to read the IDS’s story.

May Creek Farm was founded about 15,000 nights ago, in the spring of 1976. A small group of like-minded friends in their mid-20s managed to scrape together enough money to qualify for a bank loan to buy 304 acres of rolling cedars and dormant farmland, which they intended to use for a sustainable lifestyle that would preserve the land’s ecology while generating income via aquaculture, tofu production, and craftsmanship. Members lived in teepees for the first few years, as communal structures and private dwellings were gradually erected and paid for with income from paycheck jobs in Bloomington and other nearby towns.

The hardships and setbacks were constant. Members rode out blizzards in those teepees, shared living space with snakes and bats in the summer, and bathed at the HPER building on campus. Neighbors were suspicious of the community’s morals and motives (and hair, of course), and the county planning commission was deeply skeptical of their exotic proposal to compost waste rather than install a septic system. A fire destroyed the first iteration of the communal kitchen, causing a few members to drift away out of sheer exhaustion. For those who could handle the deprivations and uncertainties, the view in today’s rearview mirror is just short of miraculous. “What we’ve realized,” says Sara, “is that this is the most interesting, unique experiment — unconscious experiment — because from the very beginning we really wanted it to come from your heart, give what you can. And then, have common sense and courtesy.”

Common sense might be the best explanation for May Creek Farm’s staying power. Early on, the community incorporated and decided to limit the number of people who could live among the cedars, by selling a fixed number of 15 shares. Mobile homes have been forbidden, metal structures strenuously debated, and long-term renting allowed. Twelve homes have been built, and three shares remain undeveloped and unoccupied. As the first generation approaches its 70s, shares will probably start changing hands — and those hands won’t necessarily be a family member’s. The community asks that a prospective buyer attend at least two meetings and one social event so that some kind of rapport can be established. If the fit isn’t good, the community retains the right to buy the share to prevent its sale to an unwelcome outsider.

May Creek Farm has never been led by a marquee name, which may further explain its stability and longevity. (Needmore and Padanaram were launched and shepherded through their early years by bigger-than-life men — Larry Canada and Daniel Wright, respectively — and both communities wobbled once those men were gone.) May Creek Farm also expects considerable sweat equity from its members, especially in the maintenance and repair of the winding, unpaved road that connects their homes with the rest of the world. This monthly superchore — plus mowing of the field during summer and year-round upkeep of the community’s outbuildings — is a sharp contrast with New Harmony, where many of the idealists and intellectuals were almost comically unsuited to manual labor.

***

Ann, right, with her daughter, Sarah Barlow Yongprakit, in 2011. | Courtesy photo

Ann Barlow wasn’t a founding member of Needmore. She rolled into the community during its relative adolescence, in 1978, with five-year-old Sarah in tow. Many of the men initially objected to her becoming a member because they figured she’d be unable to take care of herself and her daughter. Ann defied their “suuper maacho triiip” — as she once described it with her mile-long, multi-octave hippie drawl — by asking the community’s tough guy to sponsor her during the probationary period. She soon proved herself capable of fixing a car engine, digging a drainage ditch, and hauling a wood stove into her house. Within two years, Ann was serving on the community’s seven-member council and organizing Needmore’s land-tax filings, as well as dealing with the mundane irritations of counterculture democracy. “It’s maddening,” she complained to a visitor in 1980. “A lot of people come very stoned to these meetings. We’ll discuss something for half an hour, and when it comes to vote on it, these people will look up and say, ‘Huh? What are we voting on?’”

By the more libertine standards of that era, Ann was a bit of a square. “I had a child, which was great because it made me not hop right into stuff,” she reminisced last summer. “I had to pay my bills. I had to make sure there was heat. If you were single, you didn’t care so much about stuff like that — just move somewhere and find someone to take care of you.” She paused before making her point more succinctly: “Sarah probably saved me.” One of Ann’s favorite memories of Needmore was teaching her daughter how to swim in the crystalline waters of the tree-shrouded community lake. “I’m a really good swimmer. And that’s something I had to offer, was teaching the kids how to swim. Not being too pushy about it. Telling them to watch the bubbles: If you get underwater and are disoriented, just exhale and watch the bubbles, and follow them.”

In 1991, Ann bought a few acres at Needmore and started a very lengthy process of building a new house for herself. Sarah had moved to Bloomington for college — then to Denver for AmeriCorps, then to Hong Kong with her husband, Boonma Yongprakit, then to Ho Chi Minh City, then Singapore, then Bangkok. Meanwhile, it took an intentional village to help Ann raise her roof. She bartered with friends and neighbors to lay the foundation for a 1,000-square-foot homestead and followed up over the next several years with sporadic installations of electrical wiring, windows, doors, and other essentials. She stuffed the walls with secondhand clothes for insulation and ultimately left some of the interior details, such as flooring, either unfinished or unaddressed.

May Creek residents discuss ways to gain community income at a council meeting in 2017. | Limestone Post

For a quarter century, Ann grew flowers in her garden — violets, geraniums, shepherd’s crook, zinnias, sunflowers, echinacea — and sold them at the Bloomington Community Farmers’ Market, where she was also known as the Lotus Lady for the bounty she brought in from Lake Lemon. In winter, she sold hand-knit scarves and hats through a craft gallery in Nashville. Her ties to Needmore, however, were fading with each passing year. Ann continued to live in her house, but she was no longer a dues-paying member of the community at the time of her death, and the reasons why were never fully articulated. She said last year that Needmore was “a lot looser” than Padanaram or May Creek Farm, “and always has been.” Her quasi-exile may have been strategic, too. “I cultivated a reputation for being slightly nuts and unpredictable,” she admitted. “It was the men who were the weirdest. If someone was being really aggressive with me, I’d hold up my hand and say: ‘Do you sleep? I can get in your house. I can come after you.’ It’s easier to maintain that rep than to have actual fights.” Last summer, she laughed about a recent visit she’d made to the community building, where a young, unfamiliar member gave her the once-over as they passed each other in the doorway. “He goes, ‘Who are you?’ And I looked him up and down, and said, ‘Who the fuck are you?’”

Lana Cruce with her father, as he builds the family home at May Creek Farm in the late 1980s. | Courtesy photo

Lana Cruce remembers this Ann Barlow: the gentle, flower-loving country woman who could morph into a flamethrower if you showed insufficient respect or tried her patience. Fifteen years ago, Lana was working on a college paper about intentional communities and arrived late to an appointment with Ann to discuss life at Needmore. Ann scorched her for not following directions correctly, then answered Lana’s questions with her usual blunt candor and free-associative storytelling. The interview wasn’t just an academic exercise; Lana herself had grown up in an intentional community, and she’s spent a lot of time over the years thinking about what it means to her and her family.

***

Lana was 7 years old when her parents moved to May Creek Farm in the late 1980s. Her mother ran a small school, Bloomington Progressive Elementary, and her father, a carpenter, spent two years building their home at the bottom of a hill in the woods. “When I was a kid out here, it was amazing,” she recalls. “We came relatively late — most of the kids were born here and lived here since they were babies — so I had immediate friendships and kids to play with in the woods and the creek.” By fifth grade, the uniqueness of her family’s lifestyle was beginning to register. “I’d bring [noncommunity] friends home, and it was like, ‘Oh, gosh!’” she mimics. “People were skinny-dipping, and we had an incinerating toilet, which was very shocking.” When Lana was old enough to drive a car, she says now with an infectious laugh, “I couldn’t wait to get into town!”

“Yeah, the kids all leave between 17 and 18,” says Mike McQueen, Sara’s husband, only half joking. The exodus is an evergreen concern for Mike, Sara, and the other two veterans of the teepee era. In Lana’s case, she was living in Bloomington and studying social work at Indiana University when her mother, divorced from her father and living alone at May Creek Farm, decided to move to Boston and rent out their home for a while. Lana gave birth to a daughter, graduated, moved to Oregon, married, boomeranged back to Bloomington, got her master’s in elementary education, had a son, then, six years ago, faced a choice: Her mother had decided to stay out east permanently, so Lana could either buy their family home in the woods or remain in Bloomington and help her mom sell it. Lana and her husband, John, made a list of pros and cons but “didn’t have big discussions, like: ‘What about in 20 years? What will the community be like then?’” Their decision seems to have been influenced more by geometry. “We just took a leap of faith,” says Lana. “The house is obviously special because I grew up there, and my dad built it. So I’ve kind of made this strange circle back to being here.”

Lana, right, speaks with, left to right, Marilyn and Nancy (a founder) during a council meeting in 2017. | Limestone Post

At the council meeting by the pond, Sara calls on Lana to give a brief report about the get-together she and 20 other “second-gen” members recently held to brainstorm ideas for community income — perhaps a subdivision of tiny houses that could be rented out short-term via Airbnb, maybe the cultivation of organic hops for brewpubs in Bloomington. Because only Lana and two other second-gen’ers actually live at May Creek Farm (the others live near and far), she’s a budding leader in the community’s preservation, which helps her address a nagging concern she sometimes feels when recalling her childhood explorations of its 300-plus acres: Only two kids live here now, and they’re hers.

“I’m lonely,” says Lana’s 14-year-old daughter, Lucy, seated at the dinner table in the house her grandfather built by hand. The confession prompts a loud “No!” from her brother, Julian, age 6, but she continues to plead her case. “We’re so far away from town on the weekends. I don’t have anyone to hang out with a lot, and I just wish there was someone close by — 15 minutes at least.” Her mother remembers a “very different experience” when she was growing up at May Creek Farm, with other kids along the road who were young enough to babysit or old enough to emulate. Lucy’s youthful lament could be considered a bad omen for the community, but Sara, one of the self-described “founding grandmothers,” feels relief instead. “We’re retired professionals, or retiring. And what’s so beautiful is that Lana bought her mother’s house, and she teaches at Harmony School, and her children are with her now. So, it’s like, I’ll cry — because we have a third generation. She’s raising our third generation.” Sara catches herself, then seasons her emotion with a dash of hard-earned fatalism: “But it’s all unknown; we have no idea what’s really going to happen.”

That was a year ago. May Creek Farm has since welcomed another family, making this the first summer together for Lana’s kids and three new teenaged neighbors.

Lana, center, moved away from May Creek to go to school, but has since returned with her husband, John, and kids, Lucy (right) and Julian, to live in her childhood home. | Photo by John Mikulenka

***

Sarah Barlow Yongprakit is the sole inheritor of her mother’s house in Needmore, but it’s unlikely she’ll ever live there. The place is too rustic for her, and after a childhood of roughing it, Sarah is unabashedly fond of basic modern comforts like hot showers in winter and air conditioning in summer. She and Boonma and their 6-year-old son, Aiden, had already been planning to move back to the United States this summer, but they’ll be returning to Denver, where they have friends, family, work connections, and three rental properties to manage.

Really miss my mom, Sarah writes in an email, a few days after the cremation. Dang her. She could have waited at least 3 more months until I was in the U.S. to see her one last time. Mother and daughter truly were best friends. Ann was also Sarah’s last tie to the place where she grew up, the seemingly limitless domain in Brown County where she roamed without a fence and splashed in the lake with her friends. But Sarah left as soon as she was able, and, nearly 30 years later, this child of intentional community is still roaming, confident in her belief that life has its way of working things out. A heavily stamped passport and habitual state of foreignness might seem antithetical to the way she was brought up, but Needmore actually prepared her well. If life ever becomes disorienting and she feels like she’s underwater, Sarah knows how to exhale and just follow the bubbles.