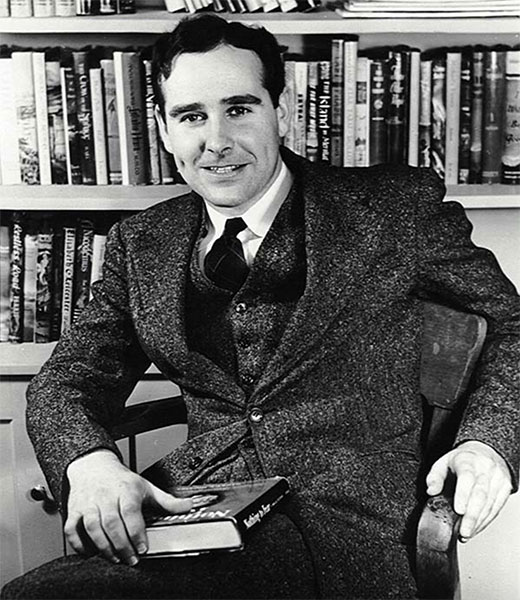

Writer Ross Lockridge Jr. (RLJ) killed himself on March 6, 1948, just two months after his book “Raintree County” was published. Pictured here, RLJ is signing autographs at an L. S. Ayres department store in Indianapolis on January 20, 1948. This is the last known photograph of RLJ. | Photo by Robert Lavelle, “The Indianapolis News.” Photographs from raintreecounty.com are used with permission of The Estate of Ross Lockridge, Jr.

“It may be that universal history is the history of the different intonations given a handful of metaphors.” —Jorge Luis Borges

The Writer As Machine. In this tale, the writer is an automaton of sorts, unable to help himself, clacking away on a typewriter for thousands upon thousands of pages, not really inventing but reiterating and concealing, an elegy for the self hidden in characters who inhabit an “almanac” of Indiana history: 50 years in the life of fictional would-be poet John Wickliff Shawnessy.

Would-be.

Though Ross Lockridge Jr. (RLJ) became a successful novelist for a very brief time, he was a failed poet.

But that runs on too far too fast even as it describes the deceased, who died by his own hands on March 6, 1948, at the age of 33.

I emailed the Borges quote above to my neighbor, a Pascal scholar, who in turn sent me an article by David Brent Johnson on RLJ’s 1948 novel, Raintree County, which tells the story of the would-be poet Shawnessy, and suggested it might be a good topic for Interchange, the radio show I produce and host on WFHB. Later in the week, at a gathering in the same neighbor’s backyard, one too many French 75s prompting me to hold forth on the only choice for the Great American Novel, Melville’s Moby Dick, local blues guitarist Jason Fickel offered Raintree County, one of his favorite books, as a contender.

If you don’t know, Lockridge killed himself just two months after his novel was published. That same novel had been chosen by MGM for a “first novel” award with a payday of $150,000 (which was in effect a rather cheap way to secure movie rights). The movie would be made nearly ten years after the suicide and starred Montgomery Clift and Elizabeth Taylor. The less said about this film the better.

Listen, this is a thousand-page book. I did not want to read it just to prove Fickel wrong. But success followed by suicide are indisputably intriguing. How bad could it be? It had been a New York Times “best seller,” so it must be readable. And there’s an audiobook after all: I walk our dogs two to three times a day, so 50-plus hours later, or roughly 150 dog walks, I’d be one of the small group of people, still living, to have read this book. In fact, I walk our dogs past the site of RLJ’s suicide nearly every day. The house is on South Stull Avenue, much the same as it was in 1948.

And one has to confess: The suicide is the story for us — even to pick up the book requires the suicide. Why else read 1,000 pages of midcentury Americana that is set in the previous century? For comparison, consider: No one reads Thomas Wolfe anymore (who wrote more than one doorstop book), though he was and still is highly praised; no one reads James Farrell’s Studs Lonigan trilogy or John Dos Passos’ U.S.A. trilogy — two works that have far more to say about midcentury America and its people.

RLJ writes “The Dream of the Flesh of Iron,” a 400-page epic poem written from 1939 to 1941, in the basement of his parents’ house. He is surrounded by the eclectic sources he worked into this “strange,” unpublished work. | Photo by Vernice Baker Lockridge. Photographs from raintreecounty.com are used with permission of The Estate of Ross Lockridge, Jr.

But Raintree County was popular and well-reviewed — a Book-of-the-Month Club main selection for February 1948 — and it occupied an interesting position in a critical debate about fiction: Novels had been “fracturing” with the world around it, split the atom, create uncertainty, and eschew linearity. Here was a real NOVEL, with plot lines and maps and intricate chronology. (Note that Norman Mailer’s first book, The Naked and the Dead, a war novel of 721 pages, was also published in 1948 and would also be made into a movie ten years on. One might argue for Raintree County as a war novel even beyond the Civil War scenes, which are some of the best in the book.)

On the proceeds of this book and those movie rights, RLJ would buy a new house and move his young family into it just three months before he killed himself. But there’s a lot to know about Ross Lockridge Jr. before he takes his novel, in a suitcase, to the one publisher he had decided he wanted to publish him. This was his first novel. He had tried to write an epic poem, The Dream of the Flesh of Iron. (This unpublished 400-page “strange” poem can be read at the IU Lilly Library here in Bloomington.) And before that, well, he’d written only very, very long letters home to his parents and his girlfriend (and future wife, Vernice Baker, who would find his body in the South Stull garage) from France where he was garnering some of the highest scores on examinations at the Sorbonne. Which is to say, there is no literary reason for RLJ to think his suitcase-filling, twenty-pound manuscript (to cite flap copy on the novel’s dust jacket) would be of interest to anyone. Except for the fact that he was a high achiever throughout his life: He bore the nickname “A-plus Lockridge” during college and at one time (if not still) had the highest GPA recorded at Indiana University.

Vernice Baker Lockridge, left, and RLJ with their son Larry Lockridge. | Photographer unknown. Photographs from raintreecounty.com are used with permission of The Estate of Ross Lockridge, Jr.

Still, it is the suicide that compels one to be an active reader — perhaps a biased one, but still alert. The book, for all its length, is small, by which I mean its narrative structure, though spanning 50 years, is all personal reflection. One might profitably compare it to Forest Gump in that Lockridge seeks to put John Shawnessy, passively, in the middle of all the seminal events of country’s history between 1848 and 1892. But, strangely, the events don’t seem to mean much to him. Its energy comes from the other characters: primarily, Flash Perkins, whom I’d be inclined to call the “hero” of the book, or at least the most sentimental; and the “Perfesser,” who is the rebarbative cynic of the book and has all the best lines (he is a kind of Mephistopheles throughout). And easily the best set piece is a send up of a revival preacher, Reverend Jarvey, tending to a widow of his flock, intercut with local men viewing a bull covering a cow. He is all Thunder and Sex. Others, all friends of Shawnessy, all out of Indiana’s native soil, “achieve” the success of their stereotype — there’s a slick politician and a railroad tycoon (best name in the book, Cash Carney), and they act as you’d expect while continuing to be friends with the man who consistently does not make his mark, the man whom they’ve all left behind. He even fails a covering of his own with a famous stage beauty of the day, Laura Golden, who had invited him to accompany her to a “Grand Ball” in New York. And his relationship with the woman he had yearned to be with all his life is simply torturous in its missed opportunities and betrayals.

Probably the most difficult part for a modern audience to respond to generously is the story of Susanna Drake, an outsider from New Orleans and cousin of the politician, whom Johnny marries out of circumstantial responsibility. She fulfills the roll of “dark lady,” somewhat literally being the daughter of a white man and his black maid. The book is less than kind to her and she is treated as a blight on Shawnessy’s life — another of his many errors that seem to occur to him rather than his being agent of them. In fact, her appearance even undermines the successful achievement of one of Johnny’s primary goals in life.

RLJ poses for a publicity shot in early March 1947, at Houghton Mifflin Company in Boston. | Photo by Arthur Griffin, Houghton Mifflin. Photographs from raintreecounty.com are used with permission of The Estate of Ross Lockridge, Jr.

This is literally a grand book of failure.

But it wasn’t the book that interested me as producer of Interchange. Instead it was the disagreement that had developed over the years between Ernest, RLJ’s oldest child, and Larry, his next oldest. Both brothers have written books about their fated father. In 1994, Larry wrote Shade of the Raintree (Viking Penguin, 1994), “a moving account of his father’s life” (according to the dust jacket blurb by former U.S. Rep. Lee H. Hamilton). Twenty years later, Ernest came out with Skeleton Key to the Suicide of my Father, Ross Lockridge, Jr., Author of Raintree County (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2014), in which Ernest asserts that his father, Ross Lockridge Jr., was sexually molested by his father, Ross Lockridge Sr.

RLJ, right, with Ross Lockridge Sr., camping at the old Lockridge farm on the Eel River in Miami County in the summer of 1942. | Photo by Ernest Lockridge, three years old. Photographs from raintreecounty.com are used with permission of The Estate of Ross Lockridge, Jr.

Meeting these two men and talking with them did not offer any clarity.

Both brothers must have needed reasons. But the nine-year-old was abandoned, the five-year-old was left. I do have some inkling of these ages and birth order and how the boys might have responded. Ernest tells a story of his father actually reading him Flash Perkins’ death scene — and it is one of the better scenes…. The child Ernest is involved in the writing of the book. The book comes into being in the same time frame: Ernest was born in 1938, in the midst of the composition of the failed epic poem, The Dream of Flesh and Iron (which could easily have also been the title of Raintree County as it evolves with the developing country via railroad travel), and he’s three when RLJ begins “American Lives,” the working title for what would become Raintree County. His memories are full of the clacking of typewriter keys as if it were the gunfire of the Civil War!

Keys to the raintree

As for the miracle of being — it is of course a miracle, but it is not necessarily a good miracle. Some lives are fortunate, and some which seem fortunate become involved in agony, and who shall say whether this is through their own fault or not? Just as poets are born so, the brave are born so, and the cowardly are born so. That is, they are born to their fate. No one blames the child of less than ten for the errors of his personality, but link by link he is bound to the grown man. —From the suicide note of Ross Lockridge Jr., March 6, 1948

Ernest Lockridge has the key to his father’s suicide. He wrote a book about it. He used an Amazon service to publish it. It’s available for purchase. It’s called The Skeleton Key to the Suicide of my Father, Ross Lockridge, Jr.

RLJ at the Old Home Place, in Henry County, Indiana, in the summer of 1946. RLJ returned to his ancestral home at the request of “Life Magazine,” which was considering a feature article. Instead, an excerpt from “Raintree County” appeared in “Life” on September 8, 1947. This photograph and others from the shoot were never published. | Photo by Jeff Wylie, Time-Life. Photographs from raintreecounty.com are used with permission of The Estate of Ross Lockridge, Jr.

Spoilers:

Jr. was molested by Sr. This claim rests in some measure on Ernest claiming that his grandfather also attempted to molest him when he was nine years old. Further, Ernest includes a chapter in his book excoriating Alfred Kinsey and his theories, condemning a so-called Kinsey culture of “acceptance” for these kinds of acts. “Unlike Freud, Kinsey did not deny the existence of incestuous child sexual abuse; he merely denied that it harmed anyone” (Skeleton Key, 80). And, in fact, “Kinsey’s wingman,” Wardell Pomeroy, was a neighbor to the Lockridges on South Stull. Ernest quotes Pomeroy praising mother-son incest as “the best sort.”

Again from Ernest, in an email to me:

Embedded in Skeleton Key is the covert culture of pervasive pedophilia, incest, and childhood sexual abuse, cocooned by institutional protection and denial, and permitted to persist, and to wreak unacknowledged havoc in the lives of innocents. Only now are we recognizing the role of denial and naiveté in perpetuating this plague on humanity. We are also just beginning to acknowledge and understand the leading role incestuous pedophilia plays in the tragedy of suicide.

Now, take this key and read Raintree County.

Larry Lockridge has the key to his father’s suicide. He wrote a book about it. Viking published it in 1994. It was reissued in a “Centennial Edition” in 2014 (RLJ was born in 1914) by IU Press. It’s called Shade of the Raintree: The Life and Death of Ross Lockridge, Jr.

Spoilers:

Jr. was manic-depressive.

“So it was one thing after another, in a relentless sequence of events that wore my father down.…”

It seems to have been a convergence of factors — of personality disorder tied in with his great ambition, of a probable biological predisposition, and of cultural and circumstantial entrapment — that led to major depression. Baffled by what was happening to him, and fearing he would never be well and could never write again, he killed himself. Life, he wrote in his final words, is still a miracle, but it is not necessarily “a good miracle.” He was not depressed because his vision had failed him; rather, his vision failed him because he was depressed. —Least Likely Suicide: The Search for My Father, Ross Lockridge, Jr., Author of ‘Raintree County’

Now, take this key and read Raintree County.

This is where I came in. And while I made two shows (aside from the general-interest program), one with Ernest, one with Larry, that presented their positions fairly, I will confess that, as a reader, I took sides. I found the book frequently ridiculous. I often laughed out loud at how bad it was, but also laughed out loud at the intended comedy. It’s inarguable that there are very great passages and scenes. And it’s when you’re inside these that you truly feel saddest. Here was something. Ultimately I’d have to call it the work of a very sad adolescent boy who is trying very, very hard.

RLJ with Larry on his third birthday in the summer of 1945. | Photo by Vernice Baker Lockridge. Photographs from raintreecounty.com are used with permission of The Estate of Ross Lockridge, Jr.

On the web post for the show with Ernest, which was the last of the series, I published, with their permission, a series of back and forth responses between Ernest and Larry in which I serve as a kind of “go-between.” The tenor of these missives is captured in these two brief selections:

Larry:

I cannot disprove Ernest’s memories of fondling by his grandfather during sleepovers after the suicide of Ross Junior. None of the rest of us encountered such behavior in this grandfather we loved and respected, so these memories are truly shocking. Assuming some truth in them, I suspect Ross Senior’s behavior was yet another bitter consequence of the suicide itself, some totally inappropriate attempt at bonding with the surviving elder grandson by a depressed and guilty person — as parents of suicides usually are. This is an explanation, not an exculpation.

[Editor’s note: Larry Lockridge’s discussion of the counter-evidence to Ernest Lockridge’s theory of sexual abuse as the key to RLJ’s suicide may be found here.”]

Ernest:

Larry posits that grief might have caused a decent man, a Doctor Jekyll, to become a sexual monster, a Mister Hyde, and that this might explain Grandpa’s attack on me on the heels of my father’s suicide….

There was no grief or love propelling the indignant, imperious Mister Hyde who attacked me violently. A predator who had invested so much precious time and energy prepping me was claiming his just reward.

My sainted father would never have abandoned me to a deviant? Last time I looked this is the same father who abandoned his entire family, the lot of us, wife and four kids, without even acknowledging our existence.

We cannot know the truth, of course. The reality of life without their father, an unfathomable suicide in a small town in Indiana, surely was a difficult one filled with the cruelties of children who convey the speculations of their parents in the most heartless ways.

I interviewed Larry at WFHB during the weekend of the Lilly Library event, and we talked for nearly two hours — which made the edit for Interchange difficult. I actually didn’t finish it. I cut out snippets of 3 and 4 minutes about specific sections of the book and then “narrated” in between them live in the studio — I even read a long bit out of the 1947 prepublication “story” in Life Magazine (which I found on eBay) about the “mythic” (everything is “mythic” in the novel) foot race between our hero, Johnny, and his running nemesis, Flash Perkins (an older, alcoholic — another key? — man-boy), while playing “Flash’s Theme” from the 1957 movie soundtrack. This “race” is a central metaphor for the whole book: the race against time; the race to achieve a greatness (in literature as in sport); the attempt to outrun a master. The book begins with Shawnessy imagining his literary skills besting Shakespeare’s.

The Lockridge children, Easter 1952: (l-r) Ernest, Larry, Jeanne, and Ross III. | Photo courtesy of Ernest Lockridge

Ernest couldn’t meet me during that weekend, so we ended up recording a phone conversation. The show was very similar in format to Larry’s. But where the conversation with Larry stuck closely to an academic interpretation of the book and his work as a “suicidologist” (more about this is available on the Raintree County website that the youngest Lockridge brother, Ross III, created and runs), the conversation with Ernest was very personal and contained moving recollections and a poem he had written for his father (see below).

It was hard not to feel for the man who was nine when his father died and to hear how palpable the loss was in his life; hard not to see Ernest’s art as another expression of this; and similarly hard not to see Larry’s work as the career that resulted from the study of a literary object or artifact, like those now housed in the Lilly Library, rather than reflection upon the loss visited upon a five-year-old. It is likely that this age difference explains so much.

And that is an entirely personal response of my own, one that makes rereading Raintree County a difficult and painful experience. Here is the book of a life that practices its author’s death in all the losses of its hero, John Wickliff Shawnessy.

CODA

The quest for the Great American Novel is a seeking after “one grand hooded phantom, like a snow hill in air.” Melville did not try to write the Great American Novel. He wrote because he was compelled to do so — he wrote toward an identity. Moby Dick is something of a mash-up — a kind of mixing together of his wish to write a bouncing “yarn” that would sell well and his wish to dive into the mysteries of knowing. You could say he got lucky. Nothing else of his reads like Moby Dick. But his life as an artist was not lucky in any estimation.

RLJ writing in his outdoor office in a field of “Murmuring Maples.” He wrote here throughout the summer of 1942. | Photo by Vernice Baker Lockridge. Photographs from raintreecounty.com are used with permission of The Estate of Ross Lockridge, Jr.

Ross Lockridge Jr. appears to have set out intentionally to write, first, a great epic poem and then to write the Great American Novel — and it’s clear to me that he had studied Melville; much of the plot of Raintree County contains interesting parallels with Melville’s Pierre: Or, the Ambiguities, possibly the greatest literary failure in history (a kraken of a failure). But this is not to call Raintree County a failed work of art. RLJ did not come close to Melville’s (and America’s) greatest book — no one has. But did he really expect to, or think it was a proper pursuit? Consider his own satire in Raintree County on the “Great American Anything” — here’s “The Great American Restaurant”:

Attractively landscaped, in the midst of the fairground, a favorite retreat for epicures, gourmands, and gastronomes, The Great American Restaurant contains a Banqueting Hall 115 feet by 50 feet, Special Rooms for Ladies, Private Parlors, Smoking-Rooms, Bath-Rooms, and Barber-Shop. Fountains, Statues, Shrubbery surround the building. In this pleasant setting, The Great American Stomach can be ministered to in the most agreeable surroundings. In the Special Rooms, the Great American Ladies can be Special in the Great American Way. In the Private Parlors, the Great American Privacy can be had by all. In the Smoking Rooms, the Great American Cigar can be smoked. In the Bathrooms, one can lave one’s limbs with a Great American Soap, pouring over one’s recumbent form the incomparable waters of a Great American Bath….

There’s a fair amount more, but you get the point. Where Melville faltered in his wish to commend Pierre to us as a “rural bowl of milk” to rest us after the whaling voyage, perhaps Lockridge succeeded, even if the milk appears to have soured.

I asked Ernest in August 2015 if he had any thoughts on David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest (Wallace committed suicide in 2008), and I said I couldn’t help but connect Wallace with Ross Jr. — typing away to stave off … something.

Ernest:

[Infinite Jest] as a fifteen-hundred page suicide note? An incredibly long sour note leading the listener into the writer’s world view? [Raintree County] is a long “sweet” one — the song of the Siren. “Suicide is painless.” Right. Oh, uh, also, the excerpt [of Infinite Jest you sent] sounds helplessly adolescent. By a writer who’s stuck there.

And of course I had to speak again of Melville’s work as the ship of literature that cannot be sunk by latecomers. Here’s something of what he wrote about that.

Doug —

Woke up last night thinking what a puny talent Wallace is, compared with Melville. Sad thing is, I’m sure Wallace would have agreed. How terrible he must’ve felt squandering all those IQ points in finding ever more “reasons” that nothing means anything at all if it adds up to less than nothing. Ecclesiastes has a similar “vision” but expresses it with exhilaration, with “infinite jest.” Likewise, there are no closed books for Melville — everything’s up for exploration that’s ongoing, infinite. “We shall not cease from exploration,” says Eliot (or something like it). Ahab’s the anti-Melville (and anti-Ishmael). Ahab’s in pursuit of life in its most inclusive form in order to KILL it — a vision of Creation as having wronged him. The Creation is infinitely beautiful, generous, but it’s also relentless and dangerous — fine, let’s destroy it. But it can’t be done, not even after thousands upon thousands of pages devoted to the effort, so let’s hang ourselves where our grossly obese corpse is the first thing our wife finds on returning home.

The raintree, planted at the Lockridge home on South Stull Ave., in summer 1962. | Photo by Ross Lockridge III. Photographs from raintreecounty.com are used with permission of The Estate of Ross Lockridge, Jr.

“Here and Now, a Drama in Five Acts”

—for my father

By Ernest Lockridge

Act One—

So what

Did Shakespeare’s father, glove-maker,

Consider his life’s purpose to be,

Or not to be?

Act Two—

Now the question’s in the open, out here,

On-stage,

What was that singular thing, his “purpose?”

Or our father’s? Our mother’s?

Ours?

Ross Lockridge Jr. and Vernice Baker Lockridge’s final resting place in Rose Hill Cemetery. | Photo by Doug Storm

Act Three—

Now let the primitive binary of this or that,

Black or white,

Here melt, thaw, and resolve itself into a dew.

Into the Vastness.

Act Four—

We push our barrows of broken stone

To the Construction Site—

Saint Peter’s, Salisbury, Stonehenge,

Los Alamos

Elsinore

The Globe

The Great Wheel of Space and Time.

Act Five—

We are Here

And Now,

If the glove fits.