A group of Indiana University BFA and MFA students in metalsmithing and jewelry design are gathered around a table at the Wells Library to investigate Alma Eikerman’s personal archives. Eikerman, whose legacy has inspired generations of artists and arts educators, was an innovative metalsmith, jewelry designer, and beloved professor at the IU School of Fine Arts (now the School of Art + Design) from 1947 to 1978.

Nicole Jacquard (left) working with BFA student Ge Bai during a trip to Wells Library to work with Eikerman’s archives. | Photo by Ann Georgescu

As the students pore over passports, travel itineraries, tickets, sketchbooks, letters from Eikerman’s family and former students, teaching files, and photographs of her art, they are hoping to understand Eikerman from a personal as well as a historical perspective. The group is preparing for their final show of the academic year, the Indiana University Metals Seminar, at the Ivy Tech John Waldron Arts Center, with an opening reception on May 5.

For this exhibition, the metalsmithing students have been asked to craft two pieces of jewelry or hollowware as a tribute to Eikerman’s artistic style and influence on modern metalsmithing. One piece will be crafted to directly emulate Eikerman’s techniques (such as raising and forging) and to incorporate her design aesthetic. And for the second piece, students will apply those skills to their own work, while also drawing inspiration from her archives.

Associate Professor Nicole Jacquard, head of Metalsmithing and Jewelry Design at IU, is with the students at the library archives. “From talking to them,” she says, “they have a much better understanding of Alma’s far-reaching influence, the groundbreaking work she did at the time, and just how rare it was for a woman in that position to be making the kind of work she was — and how it still has a resonating effect through her lasting legacy.”

Born in 1908, Eikerman grew up in rural Kansas and was one of seven children. Her independent and hard-working family instilled in Eikerman the confidence to pursue college despite the country’s rapid collapse into the Great Depression. She began her studies at Emporia State University where she pursued art and music. After graduation, she worked as a teacher in the Kansas public school system.

A thirst for knowledge led Eikerman to pursue graduate school at the University of Kansas, where she studied design and painting — and took her first metalsmithing course. The following year, she transferred to Columbia University in New York to finish her degree, which placed her at the epicenter of the country’s contemporary art scene among fierce competition. It was a place where she thrived.

Eikerman’s entrance into the art world was at the cusp of great social change in the U.S. It was the 1940s, and the upheavals of WWII saw the country shift toward even more industrialization. Many frustrated Americans started using handcrafted objects, made of clay, glass, and metal, as a way to return to a higher quality of everyday life. A small group American metalsmiths in New York City began crafting jewelry in response to this trend. Their work was modern, and they used materials outside of the normal expensive gold and precious gemstones. Their jewelry designs were not about status but were meant to empower the wearer with a means to express her individuality.

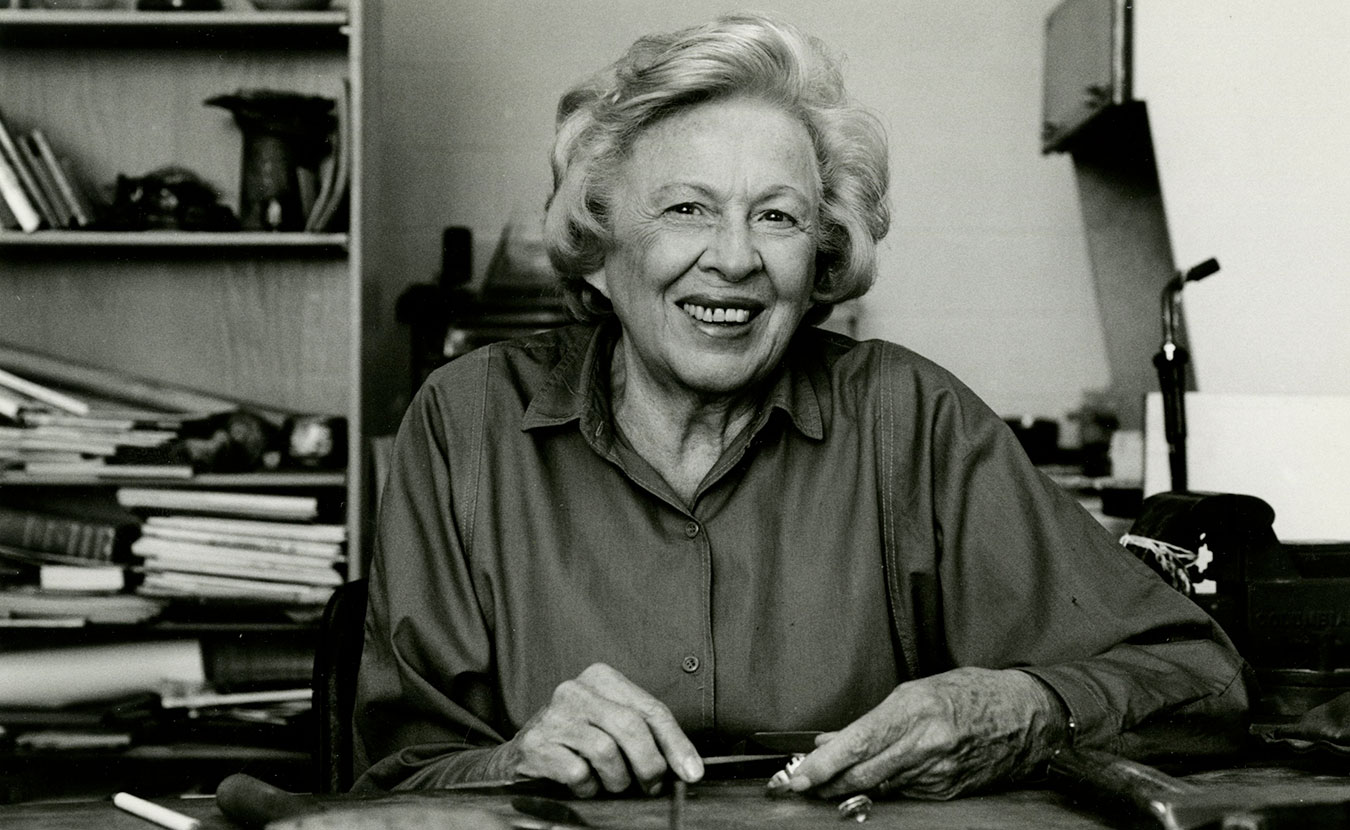

Eikerman is wearing one of her signature pieces made out of silver, green onyx, and gold. | Photo courtesy of Indiana University Archives

With the end of WWII, a large number of returning veterans required medical and psychiatric rehabilitation. An emphasis was placed on occupational and recreational activities to aid in rebuilding fine motor skills and easing emotional trauma. Veterans affairs hospitals began offering programs where recovering vets could learn a craft or a practical trade.

For example, the US Veterans Hospital in St. Louis, Missouri, offered photography, woodworking, and sewing as well as trade areas, such as jewelry making, metalsmithing, and a leather shop. Basic jewelry-making skills were therapeutic in that they built hand and forearm muscles, strengthened hand-eye coordination, and were calming for the veteran.

Vets interested in further study of the arts were now able to attend college through the GI Bill of Rights. Prior to this, would-be jewelers often learned through apprenticeships or other means, even working with dentists and foundries to master casting techniques. University programs for jewelry making and metalsmithing were scarce.

It was around this time that the face of American metalsmithing began to transform.

When IU hired Eikerman in 1947, the jewelry-making program was still in its infancy. Determined to offer her students a rich and dynamic education, Eikerman traveled the world to continue her own studies. Throughout her career, she visited Mexico, western Europe, Asia, and the Middle East to learn ancient and contemporary metalsmithing.

In the early 1950s, Eikerman received a grant to study in Denmark as an apprentice with her mentor Karl Gustav Hansen at his silverware factory. The program was taught in the traditional European guild style, in which mastery was achieved when students could make a small silver object, often an ashtray, and then remake it to exact specifications — “to the millimeter.”

A sterling silver and red brass bracelet by Eikerman. | Photo courtesy of Indiana University Archives

Eikerman returned from Denmark eager to add the study of hollowware, or hollow vessels such as teapots and serving dishes, to the metalsmithing and jewelry program.

“When looking at Alma’s students’ work,” says Jacquard, “you can tell she left a definite impression on them. There was a distinct European/Scandinavian/modernist look to the pieces coming out of IU, and it was very influential across the U.S.”

Pushing herself to continually develop and expand as an artist and metalsmith made Eikerman a central figure in American metalsmithing. Because Eikerman influenced generations of students and instructors, Jacquard says, it is hard to find anyone who has formal training in metalsmithing, be it high school or college, who does not know of Alma Eikerman.

Jacquard herself has deep roots in the Eikerman lineage. “I have been so fortunate to have studied at Bloomington High School North with Mr. Fred Brandenburger, who studied with Alma,” she says. “After that, I got to study with Randy Long [a Distinguished Professor at IU whose mentors also studied with Eikerman], and I am thrilled to be back here and a part of this amazing program.”

After their visit to the archives, the students return to the studio to put the finishing touches on their own works. They have spent the year with Eikerman’s personal historical records and her body of artistic work, while studying under Jacquard and Long, and now understand how their own work lies within the timeline of Alma Eikerman’s career and the renowned department she established at IU.

The Indiana University Metals Seminar show, inspired by Alma Eikerman’s work, will be on display at the Ivy Tech John Waldron Arts Center until Saturday, May 20, with an opening reception during First Friday on Friday, May 5.

No Replies to "Alma Eikerman’s Legacy Still Inspires Metalsmiths, Jewelry Designers"