Just over twenty years ago, citizens of Orange County’s French Lick donned orange shirts and went to the Indiana Statehouse to encourage Indiana lawmakers to grant the town a gaming license. It was a long-haul battle. Legislators had opened the doors to riverboat gambling in 1993 for eleven water-based casino licenses in Indiana — five on Lake Michigan, five on the Ohio River, and one on Patoka Lake — but a license hadn’t been given to French Lick. Today, Limestone Post and Southern Indiana Business Report look back at those early days and how today’s extensive gaming opportunities across Indiana have affected the town and its citizens.

Struggling communities in Springs Valley

Jerry Denbo was the Indiana state representative for Orange County from 1990 to 2007.

Jerry Denbo, the state representative for Orange County from 1990 to 2007, who passed away in 2014, had two goals. “One was to bring some kind of four-lane highway into the county” in order to bring people in and out, his son Rob Denbo recalls. “The other was gaming.” Those things would revive French Lick, which then suffered from 9 percent unemployment and was one of the poorest counties in Indiana.

Several times, the bill would pass the House, only to die in the Senate.

Linda Henderson of Bedford, who served in the Indiana legislature from 1992 to 1994, saw firsthand the determination of Jerry Denbo and the Orange Shirts. “Jerry was tenacious and passionate about it,” she says. “I don’t know that Orange County would have got the referendum if not for Jerry.”

The first time Henderson met Denbo was at a bean supper in Huron, in southern Lawrence County. “He introduced himself, and the first thing he said was he was going to get a casino for French Lick,” she recalls.

Denbo felt supported by the Orange Shirts, she says. “When a hundred people from your district drive up to the Statehouse, that means a lot to that legislator — you’re not out on a limb,” she says. “No one knew where Orange County was at that time, but you would see the Orange Shirts and it was like, ‘Wow, this little community is sending one hundred people to the Statehouse?’” she says. “And why shouldn’t they if it means so much to them?”

Rob Denbo is assistant director of marketing, digital, and internal communications at French Lick Resort. His first job as a teenager was working as a lifeguard at the French Lick Springs Hotel. | Courtesy photo

“It was unbelievably disappointing, frustrating, and heartbreaking in the years leading up to that legislation moving from Patoka to French Lick,” says Denbo’s son Rob. “He knew it was a tough row to hoe in the Senate, so that was expected, but it was a lot of heartbreak for him and people like Jack Carnes and others who were involved with getting the license moved.”

Rob Denbo was 20 years old when his father was elected to the Indiana legislature. He was away at college, but he kept up with news from home and his father’s efforts to help the struggling communities. And like many who grew up in Springs Valley, Rob worked at the French Lick Springs Hotel — his first job was working as a lifeguard as a teenager. At the time, the hotel was struggling. With a limited budget to make repairs, hotel staff had taken to using duct tape to hold together torn carpeting in the lobby. In the guest rooms, ceiling tiles were missing and bedspreads were old and faded.

Denbo returned to his hometown in 1996, working as a reporter at the Jasper Herald, and owned the Springs Valley Herald. Now he works in digital and internal communications for the resort. Every day he passes the historic hotels, the new sidewalks that the cities built with their share of casino tax revenue. New businesses, shops, and restaurants have opened. “I’m sure I take it for granted,” he says. “When someone sees it for the first time, it puts it in perspective the way the community has progressed.”

Economy in free fall

By the late 1990s, the Orange County economy was in free fall. Kimball International operated two factories in Springs Valley, and they had been a reliable source of employment for years, operating multiple shifts. The Kimball Electronics plant on State Road 145 closed around 1990, and the Kimball plant that produced pianos shuttered in 1996.

By the late 1990s, the Orange County economy was in free fall. West Baden Springs Hotel (above) had not operated as a hotel for decades. | Photo from frenchlickresort.blogspot.com/

“When that went dark, it felt like the whole town went dark,” Rob Denbo says. “People relied on Kimball for sponsorships and employment for so long that it was like we put up the white flag.”

The loss of tax revenue took a toll on the towns of West Baden Springs and French Lick. Sidewalks cracked and broke. Retaining walls that lined the steep residential street buckled with age and filled with weeds. Marilyn Fenton, owner of the Village Market Antique Mall and member of the Orange Shirts, says there were days when her store took in just $23.

In 1991, Luther James of Louisville, Kentucky, bought the French Lick Springs Hotel for $2.6 million and was beginning to invest in improvements, restoring the lobby’s mosaic tile floor and upgrading guest rooms. He continued to improve the property until he sold it in 1997 to Boykin Lodging Group for $20 million.

“He had it going in the right direction and that kind of motivated my dad to see what he could do,” Denbo says. Even though the French Lick Springs Hotel was a shadow of its former self and the West Baden Springs Hotel had not operated as a hotel in decades, Rob says his father was convinced hospitality and tourism would save Orange County, and having a casino was an essential part of that.

But some folks weren’t happy with the idea of the return of gambling to French Lick, which had hosted illegal gambling in the early part of the century, until Gov. Henry Schricker closed them down on Kentucky Derby weekend in 1949. Says Jeff Lane, French Lick historian and archivist, “Some people were all in favor of it, some people were not in favor, and I think some didn’t understand how necessary a casino could be to bring this community back to life.”

Orange Shirts get involved

The Patoka Lake license went unused because the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers would not allow a casino to operate on the lake. An effort to transfer the license to Orange County would gain a new level of attention when the Orange Shirts got involved.

Frustrated by the legislature, a group of residents began making trips to the Statehouse. The idea to wear orange shirts was inspired by a citizen group from New Albany that wore yellow shirts to advocate for issues unrelated to gaming.

Around 1993, a few people in Orange County convinced hotel owner James to buy about a dozen orange blazers to wear at the Statehouse to lobby for the casino license, says Alan Barnett, a former hotel employee and former director of the French Lick–West Baden Chamber of Commerce. The chamber wanted to get more people involved, but sports coats were expensive, so they switched to bright orange T-shirts.

By the mid-1990s, about twenty people were making the 108-mile trip to Indianapolis two or three times a week when the General Assembly was in session. At times, the group grew so large, they hired charter buses. In the Statehouse they crowded into hallways and House chambers. They left oranges on the desks of legislators as a calling card. With their town decaying around them, they weren’t backing down.

By the mid-1990s, about twenty people — the “Orange Shirts” — were making the 108-mile trip to Indianapolis two or three times a week when the General Assembly was in session. | Photo from the Carnes Family Collection/Steve Wilson

“They were not afraid to express themselves,” says Barnett. “They would sit up in House chambers and you always knew they were there. I believe they pushed it over the top. Until then, it was politicians and lobbyists running the campaign. When the legislature saw ordinary people there lobbying every day and the passion they had, that kind of melted some hearts.”

Jack Carnes, ‘tireless advocate’

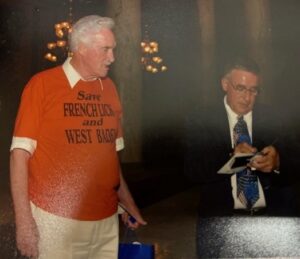

Jack Carnes didn’t need a bright orange shirt to stand out in a crowd. Standing 6 feet 6 inches, with white hair that ringed his head like a halo, he was hard to miss. Carnes’s ties to the French Lick Springs Hotel were formed as a boy growing up in the Valley.

Jack Carnes (l) and State Rep. Jerry Denbo at the Statehouse. | Photo from the Carnes Family Collection

At 14, he went to work at the hotel’s golf course. He would later become executive steward in the kitchen, supervising 30 employees who set up for parties and buffets, and he retired after a 50-year career at the hotel. But his work — and reverence — for the hotel never really ended.

One of the original Orange Shirts, Carnes lobbied for French Lick to get the casino license for more than a decade, making numerous trips to the Statehouse.

A 16-year member of the French Lick Town Council, Carnes knew that the resurgence of the hotel was necessary for residents to stay to work and raise families. “My dad knew that if things didn’t change, the town wasn’t going to make it,” says Jack’s daughter Jackie Carnes. “It’s not that my dad wanted a casino, but that was our history and that was the only thing anyone could come up with that made sense for saving the town.”

The family of Jack and Jane Carnes stands in French Lick in August 2024 on Jack Carnes Way, the street named for their father. (l-r) Jackie Carnes, John Carnes, and Connie Cox. | Photo by Carol Johnson/Southern Indiana Business Report

Like Jerry Denbo, Carnes never gave up, despite the legislature’s stubborn reluctance year after year to transfer the license. At one point, Jackie recalls telling her father she had lost faith in the effort and had doubts the license would ever be transferred. “I remember he said, ‘You just wait. We’re going to get this,’” she says. “It still surprises me his fortitude of not giving up.”

State law required that before a county could receive a gaming license, it had to hold a referendum, which took place in 2003. “That night, we were sitting at the courthouse waiting for votes,” Jackie says. “He was immensely excited for a new beginning for our community. He was not a materialistic person, his joy was seeing people thrive. To see the community bloom would be the best gift you could give him.”

And the community backed it. “The support for it is most evident in the fact that the referendum passed 65 to 35 percent, which was easily the largest margin of any Indiana county,” says Rob Denbo, comparing Orange County’s referendum results to those of other counties whose citizens voted on gaming licenses.

Sadly, Jack and Jane Carnes didn’t get to see their community’s transformation. On September 7, 2004, the couple was killed in an auto accident four miles west of Paoli. They were 71 and 68, respectively. Their deaths shocked the community. Tributes poured in for the couple and their love for their town — Jack as a tireless advocate for the casino and Jane as a teacher at Springs Valley Elementary.

A Trump hotels bankruptcy and a Cook Group restoration

Jerry Denbo didn’t get his wish until 2003, when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers finally turned their gaming license for Patoka Lake over to French Lick with Indiana Gov. Frank O’Bannon’s blessing. A bid in early 2004 was accepted from Trump Hotels and Casino Resorts. The $124 million bid included $100 million for building the casino and purchasing the West Baden Hotel, with another $287,500 for the French Lick Railway. But by August, Trump Hotels and Casino Resorts had filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, and the contract was in limbo. Gov. Mitch Daniels, installed in January 2005, requested a complete review of the contract, resulting in the firing of the gaming commission members. New commission members renegotiated the contract, but Trump chose to abandon the project. His business had lost $48.8 million by the first quarter, and his bankruptcy claimed $1.8 billion in debts, due to failed hotels and casinos in New Jersey, New York, and Gary, Indiana. It was time for French Lick to find a new partner.

Bill and Gayle Cook, founders of Cook Group, and Indiana Landmarks had been working since 1996 to restore West Baden Springs Hotel. Cook Group donated $30 million for its restoration, but finding a hotel company to purchase the restored hotel and build and run the casino wasn’t working.

The casino at French Lick Resorts is just one of the many facilities that attracts tourists to Orange County today. | Courtesy photo

Cook Group put the hotel “out there on the market, meeting with the Hiltons and the Marriotts of the world, and there were no takers,” says Chuck Franz, CEO of French Lick Resort. “The main thing [the hoteliers] said was, ‘What is going to bring people here?’ Cook supported [gaming] because it was in the interest of the community and in the interest of saving the buildings.”

Bill Cook didn’t want to own the gaming license, says Franz, and he shook hands on a deal with Gov. Mitch Daniels for the state to own it, while Cook Group operated the casino. With the reopening of the West Baden Springs Hotel in 2006, after a $100 million restoration, also funded by Cook, French Lick was ready for tourism to return.

While the casino brought in visitors, and initially it accounted for 60 percent of revenues, those gaming revenues started to decline after 2009, with the competition of nearby casinos, racinos (a combination of a horse-racing track and a casino), and online gaming. The resort, in the meantime, added facilities to attract visitors, including a Pete Dye-designed golf course that opened fifteen years ago, stables, an archery range, and sporting clays.

“Since the pandemic, the growth of golf is two and a half times,” says Franz. The winter season brings in 40,000 riders for the French Lick Railroad’s Polar Express tours, which sell out every year. Meetings and events account for 70,000+ room nights annually. The town now hosts 1.5 million visitors each year.

In addition, gaming taxes benefitted other towns in Orange County, says Jeff Lane. Paoli Community Park and Orleans town square also used gaming taxes to help build and improve the parks.

The gamble for gaming had paid off.

French Lick Springs Hotel | Courtesy photo