In August 2022, Indiana University alumna Amanda Zurawski was living in Texas and eighteen weeks pregnant with her first child when fluid began to leak down her leg. “I started kind of feeling weird, and I know now that it was amniotic fluid dripping down my leg,” said Zurawski.

When she arrived at a hospital emergency room, doctors told her and her husband, Josh, that their baby would not survive. They refused to induce her labor because the baby still had a heartbeat. Her baby would have to die in utero before they could induce.

In 2021, Texas had passed the Heartbeat Act, a law banning abortion from six weeks’ gestation, with no exceptions for pregnancies resulting from rape or incest. After six weeks, it allowed an abortion only for a life-threatening condition that put the mother at risk of death or at serious risk of substantial impairment of bodily functions. It also included civil, criminal, and professional licensing penalties for Texas physicians performing an illegal abortion. Any Texas citizen, too, had the right to sue providers to enforce the law even if they were not a party to the abortion.

Abortion options in Texas narrowed even further in 2022. When Roe v. Wade was overturned that year, a Texas trigger law banned abortion from the time of fertilization.

Although the new law continued to allow abortion for medical emergencies, Zurawski’s doctors cautioned that the state had not defined how that provision should be interpreted. They sent her home, warning her of the increased potential for septic shock, a pervasive infection that can cause organ failure and death.

“We got the diagnosis of cervical insufficiency and were told that we were going to lose the baby,” said Zurawski. “We returned home, and my water broke completely that night.” She and Josh returned to the hospital for monitoring through the night.

Still reluctant to induce, Amanda’s doctors consulted with other physicians and the hospital’s ethics board. After a night of monitoring in the hospital, Zurawski went home the next morning. Two days laters, she returned to her OB-GYN for a checkup, and on the way home, she went into septic shock.

“It was so scary. Suddenly, I was so out of it. My teeth were chattering. I couldn’t put together a sentence. I was freezing cold even though it was 103 degrees outside,” said Zurawski. “By the time we got home, I couldn’t even walk to bed. Josh called the doctor and packed a bag for the hospital.”

After three days in intensive care, Zurawski recovered, but her reproductive organs were scarred and her fallopian tubes closed. Her uterus collapsed even after surgery to remove scar tissue caused by the infection. Her reproductive options are surrogacy or in vitro fertilization. She has post-traumatic stress disorder and has sought counseling.

Amanda Zurawski and nineteen other women sued the state of Texas because its extreme abortion ban prevented doctors from providing necessary medical treatment. The women were denied proper healthcare despite facing severe and dangerous pregnancy complications. (above) Zurawski speaks at a press conference. | Photo by Michael Guilbert from Splash Cinema/Center for Reproductive Rights

Represented by the Center for Reproductive Rights, a global advocacy group, Zurawski and nineteen other women — all of whom had suffered pregnancy medical complications but couldn’t get care because of the vagueness of the law — sued Texas.

A Travis County judge issued an injunction, allowing Texas women to get abortions if their doctor made a good-faith judgment that an abortion was necessary. Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton appealed the ruling, and the Texas Supreme Court granted a review.

On March 22, 2024, the Texas Medical Board defined “emergency medical condition” as “a life-threatening physical condition aggravated by, caused by, or arising from a pregnancy that, as certified by a physician, places the woman in danger of death or a serious risk of substantial impairment of a major bodily function unless an abortion is performed.”

But on May 31, the Texas Supreme Court refused to clarify the current exceptions under Texas abortion law.

“This ruling feels like a gut punch, not just for pregnant Texans but also for doctors in our state,” said Zurawski. “Unfortunately, the Texas Supreme Court has shown us that they do not wish to help pregnant Texans access healthcare, and they do not want to help doctors practice medicine in the state of Texas. The Supreme Court had the opportunity to provide clarity, but we are right back where we started. This ruling is heartbreaking, but this is not the end. Although the State wants to pretend we are invisible, let me be clear that in this lawsuit were twenty-two inordinately strong women who demanded justice. We are the faces of women across the country standing up and demanding to be heard.”

What constitutes a serious health risk?

In 2022, Indiana was the first state to enact an abortion ban after the reversal of Roe V. Wade, allowing three exceptions, including pregnancy resulting from rape or incest. The other two exceptions state that “an abortion may be performed, including when (1) the abortion is necessary to prevent any serious health risk of the pregnant woman or to save the pregnant woman’s life; and (2) the fetus is diagnosed with a lethal fetal anomaly,” which is medically defined as a genetic or physical defect in the fetus.

Like Texas, Indiana has not clarified serious health risks or a life-threatening condition in its abortion ban. Untested in Indiana, the question remains: What conditions might qualify a woman for an abortion?

No one knows, said Jody Madeira, Richard S. Melvin Professor of Law and co-director of Center for Law, Society & Culture at the Indiana University Maurer School of Law.

Jody Madeira is the Richard S. Melvin Professor of Law and co-director of Center for Law, Society & Culture at the Indiana University Maurer School of Law. | Courtesy photo

“If you have health issues, serious health issues — God only knows what that is,” she said.

Because of the penalties in states like Indiana, providers are now so cautious that they allow medical conditions to worsen, or they don’t act at all. According to the Guttmacher Institute, women now have much more limited options when it comes to abortion and reproductive care, even in emergencies.

“Abortion is now a tremendously dangerous practice [for physicians],” said Madeira. “Even if they exercise reasonable medical judgment.”

Under Indiana’s new law, providers face a Level 5 felony punishable by one to six years imprisonment, a fine up to $10,000, and revocation of their medical license.

“We’ve already seen that our attorney general is willing to bend the rules and put physicians who perform legal abortions in a dangerous position,” Madeira said, referencing the case of Dr. Caitlin Bernard, an IU Health physician in Indianapolis who performed an abortion on a 10-year-old rape victim from Ohio.

In September 2023, Indiana Attorney General Todd Rokita filed a lawsuit against IU Health, alleging it violated HIPAA, federal medical records privacy law, and state law. That case was recently dismissed after the U.S. District Court found Bernard’s alleged failure to obtain a patient’s written authorization did not indicate systematic failure on the part of IU Health.

Defining what constitutes a medical exception is now the crux of a case in Monroe County. At a bench trial in Monroe County Civil Court, a group including Planned Parenthood in Indiana and other parties debated emergency medical conditions that created a severe health risk, allowing an abortion.

Indiana Attorney General Todd Rokita | Photo from in.gov

The plaintiffs also raised the issue of whether poor mental health constituted a severe health risk to a pregnant woman. And they questioned the provision requiring abortions to be performed only in a hospital and whether to make terminated pregnancy reports public, an ongoing fight led by Attorney General Todd Rokita and the Indiana State Department of Health.

On September 11, 2024, a Monroe County special judge refused to expand the exceptions included in SB1. Planned Parenthood has appealed that ruling to the Indiana Court of Appeals.

This case and others beg the question: Do patients really want their doctor’s hands tied in a medical emergency?

“Who’s to say what a serious health condition is?” said Madeira. “You’re jeopardizing your health because the doctors are waiting on the guidance of lawyers. I believe this kind of case should succeed on the merits because the life and health exceptions are so restrictive or vague, which is even more dangerous.”

High-risk conditions like pre-eclampsia (high blood pressure during pregnancy), placenta problems, congenital or genetic conditions in the mother or baby, preterm birth, miscarriage, and ectopic pregnancies can create serious risks. And some critical pregnancy complications may require an abortion to resolve the emergency.

As reported in the Indiana Capital Chronicle, IU Health’s Dr. Amy Caldwell, one of the plaintiffs in the Monroe County case, testified that the only way to resolve conditions such as severe morning sickness, placental abruption (separation of the placenta from the uterus), and placenta previa (where the placenta covers the cervix and causes serious bleeding) is by terminating the pregnancy.

“

Although the State wants to pretend we are invisible, let me be clear that in this lawsuit were twenty-two inordinately strong women who demanded justice. We are the faces of women across the country standing up and demanding to be heard.

”

—Amanda Zurawski

A month ago, Victoria (first name used for privacy and safety) started having cramps, dizziness, and vomiting. She saw her doctor, who brushed off her complaints. In the ER a few days later, she found out that she was seven weeks pregnant with an ectopic pregnancy, a condition where the fertilized egg attaches outside the uterus.

“I had no idea that I was pregnant until the morning that I finally went to the ER. I was shocked. I’m still shocked,” she said. “At the ER, they told me that if I had waited another day, I would have died.” Despite the fetus having a heartbeat, surgery was required to terminate the pregnancy. A fetus can survive only in the womb, and in an ectopic pregnancy, its growth in a fallopian tube or elsewhere outside the womb can lead to bleeding, internal organ damage and even the death of the mother.

“Not only am I physically still recovering and have to grieve what could have been a normal pregnancy, I feel scared,” Victoria said. “After their first ectopic pregnancy, women often experience this more than once. The thought of this happening again is horrific.”

IU Health maternal-fetal medicine specialist Dr. Caroline Rouse regularly treats patients with serious pregnancy complications.

“What’s hard about this law [SB 1] is that every single patient is unique and comes with a constellation of medical conditions, personal experiences, and risk tolerance. Being forced by the legislature to break things into this ‘life-threatening’ or ‘definitely not life-threatening’ is hard,” she said.

“It’s well documented in the literature that a pregnancy is dangerous. If you have an abortion as opposed to carrying a pregnancy to term, you are fourteen times more likely to die just carrying the pregnancy to term.”

IU Health OB-GYN Tracey Wilkinson agrees. “It’s like everyone’s worst nightmare keeps happening, states are finding new ways to attack and limit people’s access to evidence-based healthcare, whether that’s infertility treatments or pregnancy termination and abortion,” she said.

Indiana’s abortion ban required a quick response from healthcare providers around the state. Rouse participated in creating IU Health’s response to when it is legal for doctors to provide an abortion. The resulting protocol includes a rapid response team that deals with individual emergency cases. The policies and procedures are discussed in detail in “Abortion Care After the Dobbs Decision: An Academic Health System’s Response to a Statewide Ban,” an article published in Academic Medicine Journal.

An IU Health spokesperson said, “The RH-RRT [rapid response] has been employed,” but would give no further information, citing patient confidentiality.

Federal law preempts state law

To ensure that a seriously ill person experiencing a medical emergency receives care and is not turned away from the hospital, these emergencies, including pregnancy emergencies, are governed by federal law. However, in states like Indiana that have the most restrictive abortion laws, state and federal regulations may conflict.

The Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act, or EMTALA, applies to all hospitals with Medicare funding and emergency departments. Under the law, a person has the right to emergency medical care, regardless of payment, until their condition, including pregnancy labor complications, has been stabilized.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), which is part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, defines stabilizing care: “If a physician believes that a pregnant patient presenting at an emergency department is experiencing an emergency medical condition as defined by EMTALA and that abortion is the stabilizing treatment necessary to resolve that condition, the physician must provide that treatment.”

“

Under Indiana’s new law, providers face a Level 5 felony punishable by one to six years imprisonment, a fine up to $10,000, and revocation of their medical license.

”

Under EMTALA, failure to provide stabilizing care could result in a hospital losing its Medicare funding status, drastically impacting most hospitals’ bottom lines. Medicare and Medicaid payments account for most of a hospital’s funding, with $944.3 billion paid by Medicare in 2022.

Further, the CMS guidance explains that when state law prohibits abortion and does not include an exception for the life of the pregnant person or the exception is more narrow than EMTALA’s emergency medical condition definition, state law is preempted by federal law.

Recently, the U.S. Supreme Court consolidated and heard Idaho v. United States and Moyles v. United States, a clash between Idaho’s law and EMTALA. Idaho law prohibited hospitals from providing abortions as stabilizing medical care. At that time, six pregnant women had been airlifted to another state for emergency medical care while pregnant. The Supreme Court heard arguments in April 2024, and the decision was released on June 27.

The court dismissed the case, saying that the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit had not considered the merits. It issued a preliminary injunction, allowing Idaho pregnant women to receive stabilizing care, including abortions. The court returned it to the Ninth Circuit to hear arguments on the case’s merits, failing to resolve the issue of whether EMTALA preempts Idaho law.

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito | Photo cropped from supremecourt.gov

In his dissent, Justice Samuel Alito opined that no preemption existed because EMTALA required emergency stabilizing treatment for the fetus rather than for the mother, thus not requiring an abortion. His dissent hinted at creating the personhood status of the fetus and a potential roadmap for future EMTALA cases. The issue is expected to be returned to the Supreme Court.

In addition, the Supreme Court again rejected a request on October 7, 2024, by the Biden administration to resolve a dispute over EMTALA guidance on abortions, requesting that the case be returned to lower courts. The Biden administration request came after the decision on the Idaho case. As a result, a Texas lower court ruling which blocks the enforcement of EMTALA in Texas now remains in place. The issue is unresolved nationally.

At IU Health, the rapid response team considered how EMTALA impacted Indiana’s ban. They pointed health care providers to the Medicare and Medicaid guidance that says EMTALA requires stabilizing treatment for all patients, regardless of state law.

“It really should be shocking to people how big of an effect this [Indiana] ban has on the health system,” said Rouse. “Decisions made by the people in the legislature are intended to put themselves between the patient and their healthcare decision. [They] are inserting themselves into people’s medical decisions. We are now operating in a landscape that requires physicians to have medical and legal knowledge to back up our daily decisions.”

Healthcare consequences of a restrictive abortion ban

Despite an abortion ban, pregnant women may seek an abortion because they face domestic violence, too many mouths to feed, or other poor economic conditions. Lack of access to prenatal or pregnancy healthcare can also leave pregnant women without reproductive health options.

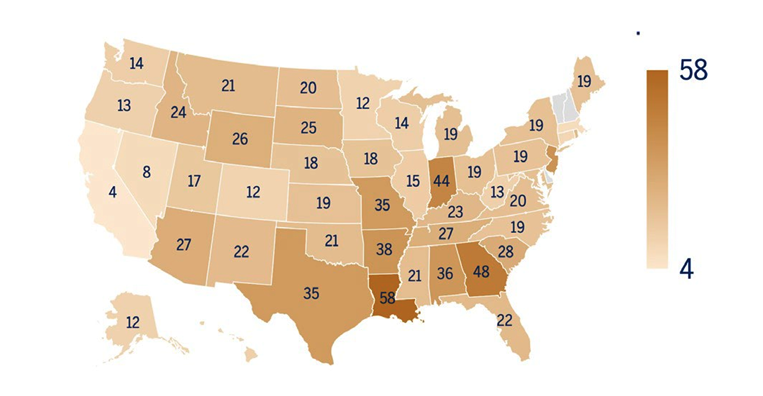

A 2022 study conducted by The Commonwealth Fund found that states that banned abortion have fewer maternal health practitioners, more maternal care deserts, and a lack of prenatal care options. Maternal and infant mortality rates also increase. Indiana is one of those states.

Indiana has struggled for many years in improving maternal mortality and infant mortality, having the third highest maternal mortality rate in the U.S. at 44 deaths per 100,000 live births. In infant mortality, the state has 7.2 infant deaths per 1,000 births, placing it among the top 10 states with the highest infant mortality rates.

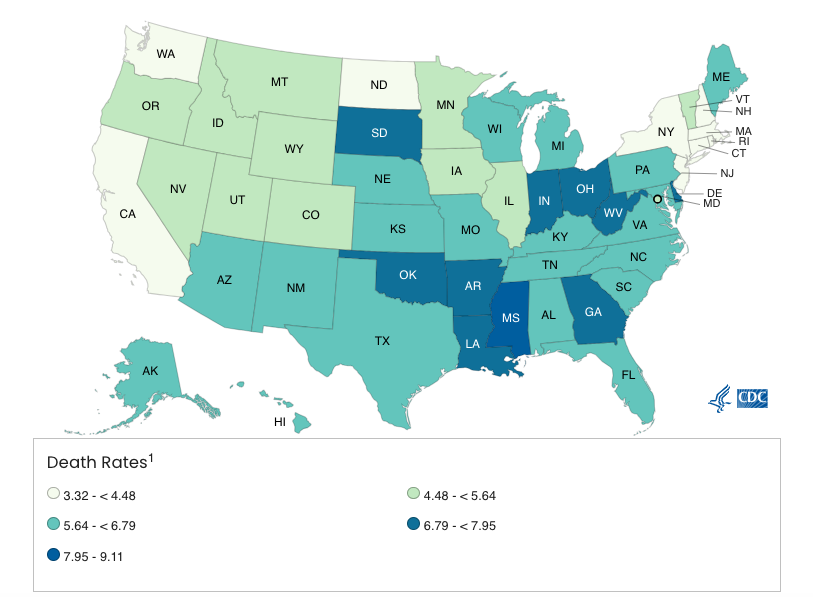

U.S. Maternal Mortality Rates

as of 2022, per 100,000 live births

2022 U.S. maternal mortality rates per 100,000 live births. | Source: Indiana University Public Policy Institute, Center for Research on Inclusion and Social Policy; World Population Review

The World Health Organization defines maternal mortality as “the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and the site of the pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes.” The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says eighty percent of such deaths are preventable.

According to an Indiana University Public Policy Institute report, lack of access to health services, such as prenatal and postnatal care, contributes to these poor outcomes. In addition, a shortage of OB-GYNs is a factor.

The 2017 paper “Defunding of Women’s Health and Rising Maternal Mortality in Indiana” argues that the Indiana legislature long fought against provisions to support women’s health, battling with Planned Parenthood and declining public health dollars dedicated to women’s health.

“

We’ve already seen that our attorney general is willing to bend the rules and put physicians who perform legal abortions in a dangerous position.

”

—Jody Madeira

As of 2010, Planned Parenthood clinics comprised 30 percent of Indiana’s family planning centers, many in rural areas. The clinics provided women’s healthcare and family planning assistance. Still, in 2011, the Indiana legislature prohibited Planned Parenthood from providing any services via Medicaid.

As a result, Planned Parenthood clinics shut down, and, to date, only eleven Planned Parenthood centers are available throughout the state.

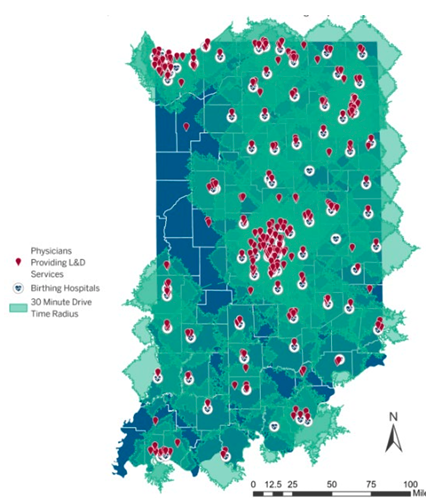

The 2023 March of Dimes’ report “Where You Live Matters: Maternity Care in Indiana” found a 12 percent decrease in birthing hospitals from 2019 to 2020. During the COVID pandemic, some reproductive health centers and hospitals temporarily closed or reduced their capacity. As a result, women had to delay or cancel visiting their OB-GYNs, resulting in a significant challenge, especially for low-income and Black and Hispanic women.

The report finds that twenty-two counties in Indiana are maternity care deserts with zero hospitals or birth centers, and six counties have fewer than two hospitals or birth centers.

Monroe and Greene counties have full access to maternity wards, whereas Lawrence, Morgan and Owen County have moderate to low access. Brown, Martin, and Daviess counties have no access to maternity wards. Twenty-one percent of Indiana’s rural women travel more than thirty minutes to a birthing hospital, meaning they traveled 3.2 times farther than women living in areas with full access to maternity services.

Distance from residence to birthing centers in Indiana. | Source: Indiana Maternal Mortality Review Committee

In addition, the report found that in 73 percent of those counties with maternal care deserts, women have an increased vulnerability to adverse health outcomes plus a 51 percent likelihood of inadequate prenatal care — a significant determinant in infant mortality.

In Indiana, nearly one in six birthing people receive no or inadequate prenatal care, which is higher than the national average.

As a result, the cumulative effects of maternal health deserts, physician shortages, lack of public health funding, and other factors on mortality often create a footprint for failing maternal and infant mortality rates. Studies have found that states with restrictive abortion bans tend to have fewer OB-GYNs, more maternal health deserts, and overall limited access to reproductive care, often resulting from a long-term lack of emphasis or funding for women’s healthcare. The question becomes: Are these states prepared for increased births given their current status of women’s healthcare options?

For minority and rural populations, the impact is dramatic. Today, according to the 2023 Annual Report of the Indiana Maternal Mortality Review Committee, Black women in Indiana have a maternal mortality rate of 156.3 deaths per 100,000 births, while white and Hispanic women each have a maternal mortality rate of 90.7 deaths per 100,000 births. Inadequate prenatal care due to insufficient prenatal health services is a significant contributor.

The mental health of a pregnant woman also factors into maternal morbidity and mortality. A 2024 study on perinatal mood and anxiety disorders found that from 2008 to 2020, among 750,000 privately insured pregnant people, 93 percent had worsening mental health conditions, and one in nine pregnancy-related deaths from 2008 to 2017 occurred in people with mental health conditions, with 100 percent of those deaths being preventable.

The Policy Center for Maternal Mental Health gives Indiana a D+ for failing to provide mental health screening and for a lack of mental health providers. Although a significant number of states have passed legislation addressing and funding maternal mental health, Indiana has not.

As for infant mortality, an Indiana Department of Health report in March, analyzing 2022 infant deaths and some preliminary 2023 numbers, found that the rate had declined from 7.2 deaths per 1,000 births in 2022 to 6.5 deaths per 1,000 births in 2023.

In 2021, the rate was 6.8 deaths, in contrast to the U.S. rate of 5.9 deaths. Again, factors of perinatal risks and the mother’s health and well-being heavily influence these numbers.

Infant Mortality Rate by State

as of 2022

2022 infant mortality rates by state, per 1,000 live births. | Source: CDC National Center for Health Statistics

A recent Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health study found that infant mortality in Texas had increased as a result of the state’s restrictive abortion ban. Researchers studied infant death certificates from Texas and the U.S. for 2021–2022.

They found that Texas infant deaths had increased by 12.9 percent, whereas the U.S. infant death rate had increased by only 1.8 percent during that same period. The study’s researchers suggested that “restrictive abortion policies may have important unintended consequences in terms of trauma to families and medical cost as a result of increases in infant mortality.”

Keeping OB-GYNs in Indiana

Indiana maternity care is facing a significant physician shortage. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics for Occupation and Employment Wages for 2023, Indiana has 470 OB-GYNs in a state of 1.5 million reproductive women, down from 692 OB-GYNs in 2021. The outcome is worse for rural Indiana hospitals. According to the Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform, Indiana has 54 rural hospitals, 52 percent of which have no practicing obstetricians.

Finding OB-GYNs to provide care or encouraging medical students to stay and practice in Indiana may be even more challenging because of Indiana’s restrictive abortion ban.

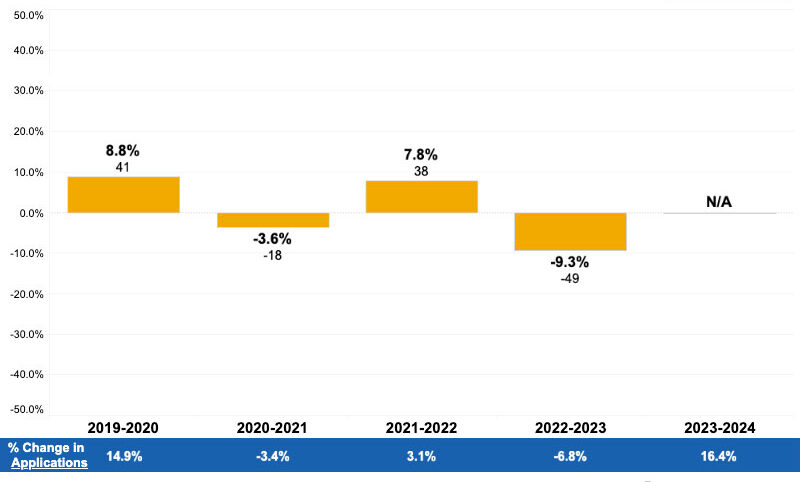

The ban’s penalties on physicians may also worsen that shortage. An American Association of Medical Colleges survey found that, since Dobbs, there has been a steady decline in residency applications in states with abortion bans. These applications are a potential early indicator of a medical resident’s choice of specialty, where they will continue their studies, and perhaps for future practice.

The study also found that for the last two years, students graduating from medical school and moving on to residency were less likely to move to those states with abortion ban restrictions, an indication that physicians are starting to factor in these restrictive environments upon completion of their training.

Further, in OB-GYN specialties, the AAMC study found the number of applicants in this specialty declined by 4.2 percent in the past two years, compared with a .6 percent drop in states where abortion was still legal.

Percent Change in Applicants for Indiana OB/GYN Residencies

According to an IU School of Medicine spokesperson, Indiana’s residency numbers have not changed to date. However, during the 2022 special legislative session, IU Health conducted an informal survey to understand the potential impact of the abortion ban on graduate medical education. More than half of those surveyed indicated they would be much less likely to seek future employment in Indiana because of an abortion ban.

Also, trainees stated they would be less likely to seek future employment in Indiana if providers were criminalized. A week before the ban went into effect, IU Health received notice from several faculty candidates who rescinded their interest in practicing in Indiana.

And it’s not just OB-GYNs. The abortion ban also impacts who stays or comes to Indiana to live, according to Michael J. Hicks, George and Frances Ball Distinguished Professor of Economics at Ball State University. For the first time in recent years, Indiana is seeing a significant decrease in college-age graduates staying in or migrating to the state, Hicks said. Educational attainment has much to do with these changing patterns, but a restrictive abortion ban is an additional disincentive to settle in Indiana, he said.

“For the past six years, educational attainment in the state among adults has decreased because of the decline in college-going rates, which have not been so acute since 2015,” said Hicks. “We are seeing a 12 percent decline.” He predicts lower-income jobs will drive the state, whereas jobs requiring college degrees or higher-earning positions will remain stagnant.

“

It really should be shocking to people how big of an effect this Indiana ban has on the health system. Decisions made by the people in the legislature are intended to put themselves between the patient and their healthcare decision.

”

—Dr. Caroline Rouse

A 2023 Economic Policy Institute study found states with restrictive abortion bans, like Indiana, have, on average, lower minimum wages for hourly workers.

Indiana’s minimum wage is $7.25 (a number that hasn’t changed since 2008), equating to $15,080 annually. The federal poverty level is $15,060. According to a Guttmacher Institute survey of abortion patients, 73 percent of those surveyed said they could not afford to have a baby. Other reasons given were that a child would interfere with a woman’s education, work, or ability to care for dependents (74%) and that she did not want to be a single mother or was having relationship problems (48%).

Cheryl Rich of the Equity Clinic in Illinois says most of the clinic’s clients are struggling to care for themselves and their families. Most women think, said Rich, “Am I going to be able to take care of this child financially? Am I going to be able to give this child, especially with other children, the attention they need?”

Citing a recent study by Amanda Weinstein and Curtis Lockwood Reynolds, Hicks said women are not moving to places with restrictive abortion bans, because they don’t offer the quality of life they seek. The study found women prefer to live in states with more progressive gender roles and attitudes, meaning they may be more sensitive to policies impacting health and well-being.

A second study supported these findings, showing that state policies that limit rights based on sexual orientation, gender, race, parenthood status, and other factors could result in negative economic consequences, especially regarding declining interstate migration and decreases in those seeking employment and pursuing higher education.

“Indiana cannot be outside the mean on culture war issues and then expect it not to have economic consequences,” said Hicks. “We’re digging a hole that is deeper and deeper each time, and we don’t have the luxury of being off-putting to anyone.”

In April 2023, eight months after her ordeal, Amanda Zurawski spoke before a hearing of the Senate Judiciary Committee. She told the committee about her grief, her PTSD, and her ongoing struggle to get pregnant.

“I nearly died on their watch,” she said, referring to her senators, Ted Cruz and John Cornyn, who were not present at the hearing. “And furthermore, as a result of what happened to me, I may have been robbed of the opportunity to have children in the future, and it’s because of policies they support.”

She was lucky, she said, to have health insurance, an understanding employer, and a supportive husband. Other women facing restrictive abortion laws, including those in Zurawski’s home state of Indiana, may not be that fortunate.

“What happened to me was horrible, but I was one of many,” she said. “What about all of the women that don’t have those same opportunities, that don’t have access to health care, that don’t have health insurance, that don’t have a partner? What about them?”

Learn More

Video: “I nearly died on their watch.”

In an Austin, Texas, hospital in 2022, Amanda Zurawski was denied abortion care under the Texas’s restrictive abortion laws, despite her nearly dying from septic shock. At a 2023 hearing of the Senate Judiciary Committee, she told Texas senators Ted Cruz and John Cornyn that she “nearly died on their watch.” She added that she “may have been robbed of the opportunity to have children in the future.”

Documentary: Zurawski v Texas

Josh and Amanda Zurawski took questions from the audience after the screening of “Zurawski v Texas” in Indianapolis on October 13, 2024. | Limestone Post

The documentary film Zurawski v Texas tells the story of three women, including Amanda Zurawski, who were denied medically necessary abortion care. The Center for Reproductive Rights says the film shows “the stark reality of what it means to be pregnant in a U.S. state that has banned abortion — and the bravery, grit and determination that it takes to speak out.” Directed by Maisie Crow and Abbie Perrault.

The film screened at the Heartland International Film Festival in Indianapolis on October 13, and will show again on October 19. Learn more and buy tickets at heartlandfilmfestival.org.

Read:

“Rhetoric versus reality: Addressing common misconceptions about abortion,” by Sofia Resnick in Indiana Capital Chronicle.

“Advocates for Women’s Healthcare Have Plans for Stricter Bans,” by Rebecca Hill in Limestone Post, about how various groups provide abortion access despite further restrictions by many states. Some groups model their work on the underground abortion providers of the 1960s and early 1970s, before Roe v. Wade, which granted federal protection of abortion rights.

The Bloomington Health Foundation is an underwriting partner of Limestone Post. As the local philanthropic expert for improving community health for more than 50 years, Bloomington Health Foundation is expanding its mission to address the most pressing health needs in Bloomington and neighboring communities.

The Bloomington Health Foundation is an underwriting partner of Limestone Post. As the local philanthropic expert for improving community health for more than 50 years, Bloomington Health Foundation is expanding its mission to address the most pressing health needs in Bloomington and neighboring communities.