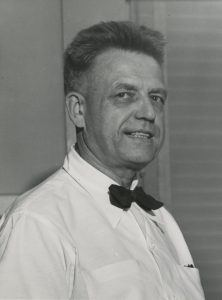

More than 100 years ago, Harvard-educated biologist Alfred C. Kinsey came to Indiana University to teach and pursue his studies of gall wasps. He conducted research on the wasps’ structure, size, and mating habits. But like many scientists of the day, he was interested in other aspects of biology, says Judith Allen, IU professor of history who is writing a book on Kinsey. “He was writing in the ’20s with peer scientists at other universities about sexual and reproductive issues,” she says.

Kinsey taught the class Marriage and Family to married students and seniors at IU. | Courtesy photo, Copyright © 2017, The Trustees of Indiana University on behalf of the Kinsey Institute. All rights reserved.

In 1938, the Association of Women Students petitioned for a course on marriage, and Kinsey taught Marriage and Family to married students and seniors. Students in the course wanted to learn about sex, and Kinsey found there was little clinical research on the topic. He decided to focus on this scientific niche and began applying the research techniques for analyzing and coding from his gall wasp studies into surveys on sex.

By 1940, he had devoted himself full time to human sexuality research at IU. Kinsey went on to establish the Institute for Sex Research in 1947, publishing his best-selling book, Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, along with his associates Wardell B. Pomeroy and Clyde E. Martin, in 1948.

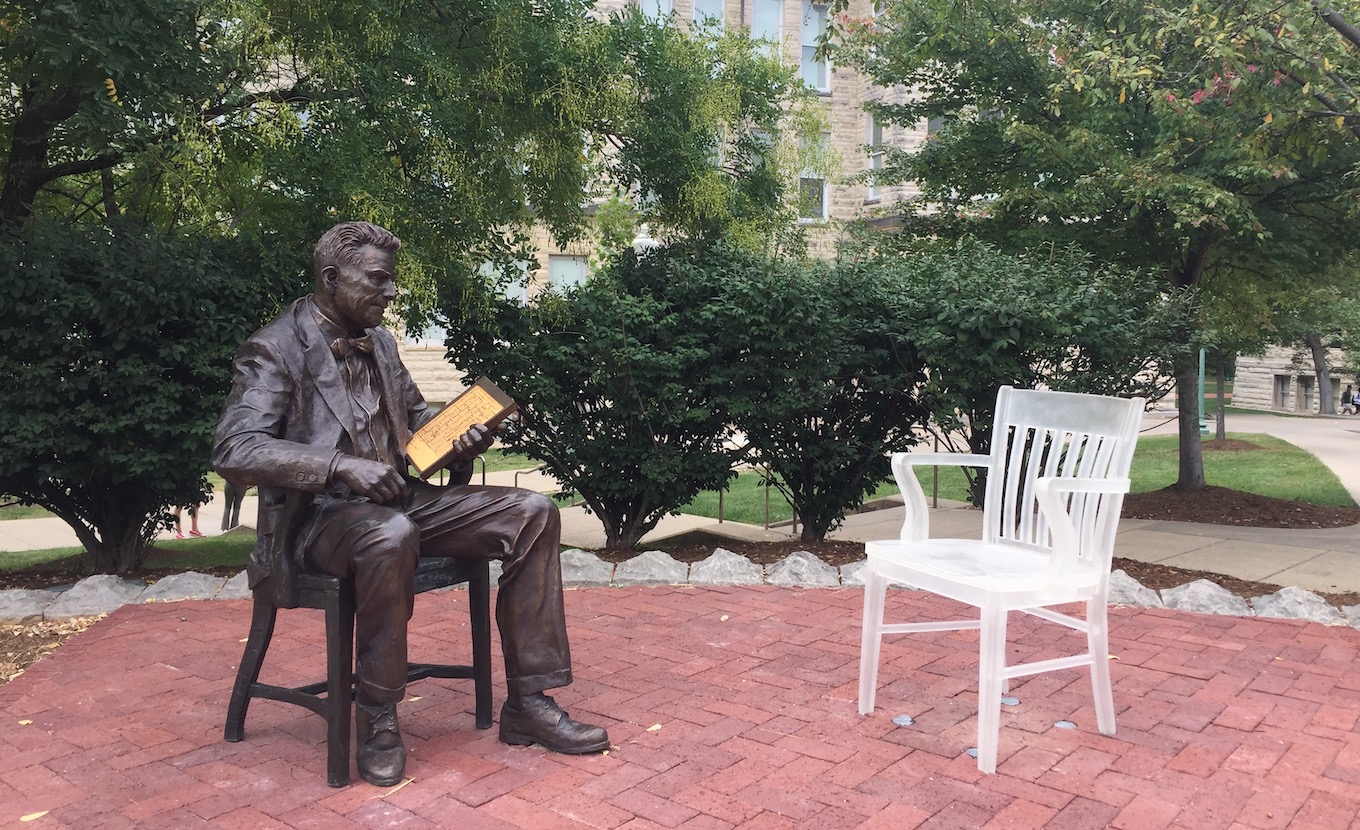

When Kinsey founded the Institute for Sex Research, it was housed in Swain Hall East, which was the biology building. It later moved to Wylie Hall, then Jordan Hall (now called the Biology Building) and then to Morrison Hall. Its latest move is to Lindley Hall, which was originally Science Hall. It sits next to Dunn’s Woods, with a Jean-Paul Darriau’s 1965 bronze sculpture The Space Between Adam and Eve at the edge of the woods nearby. Fittingly, a life-size bronze sculpture of Kinsey was installed this month in the grassy area between Lindley Hall and Simon Hall, facing the institute’s home in Lindley Hall.

The Kinsey sculpture is by Melanie Cooper Pennington, a faculty member at the IU Eskenazi School of Art, Architecture + Design. Liana Zhou, director of the Kinsey Institute library and collections, says there was great anticipation about the sculpture, and in late August when the bronze work was delivered, a co-worker called her to say, “He’s here!”

The largest research collection of its kind

Kinsey, who died in 1956, would likely be surprised at the expansion of research and relevance of this Bloomington-based institute, now 75 years old. The library collection alone has grown from an initial 6,000 artifacts to more than 600,000 books, papers, art objects, photographs, films, and other items.

Justin Garcia, executive director of the Kinsey Institute at IU. | Courtesy photo

“It’s the largest research collection of its kind that deals with issues of sexuality and gender and relationships, documenting sexuality across the world and over at least 2,000 years of human history,” says Justin Garcia, executive director of the Kinsey Institute. “Scholars still visit us every year who are working on books and articles and trying to dive into the archive. It’s what makes Kinsey so unique.”

Garcia sees the library and archives as one of the biggest successes of the organization. “We’re not just the shadow of [Kinsey’s] original study, and we’re continuing to do cutting-edge research with really tremendous faculty and staff.”

Encouraging deeper understandings

One of the institute’s newest programs is a partnership between the Kinsey Institute and the IU Kelley School of Business, called the Kinsey–Kelley Center for Gender Equity in Business. The center’s first class was team-taught to MBA students in the spring on the topic of #MeToo and sexual misconduct in the business world. April Sellers, the Pam Meyer Yttri Director of the new center, was one of eight instructors for the first class. She is working now to develop more courses, including one that will be required for all business school undergraduate students on business ethics.

Garcia says the purpose of this center and its programs is to encourage in future business leaders a deeper understanding and awareness of these issues, not a “check the box” 60-minute sexual harassment program that most businesses require employees to take, but don’t appear to change behaviors.

April Sellers, the Pam Meyer Yttri Director of the Kinsey–Kelley Center for Gender Equity in Business. | Courtesy photo

“We see over the last few decades higher rates of sexual harassment in the business environment,” Garcia says. “That harassment is leading to women, sexual and gender minorities, and racial and ethnic minorities leaving the workforce. It has an impact on the quality of work, on the retention of top staff. And beyond the company bottom line, it’s bad for people’s mental and physical health.”

Sellers says, “When you look at the number of women in the boardroom, the number of women in management areas, [that] adds a new appreciation for gender identity in the workplace. … There is so much work still to do. The numbers of women in C-suites or even just on boards is depressingly small still.”

One of the big plans is for the center to reach out to corporate partners, particularly Indiana businesses, to help identify issues and how the business school can apply the latest learnings and research. According to the Kelley School, about 680 Indiana students will be taking the undergraduate class in business ethics this year, and ten graduate students will take the MBA course.

“An effort like this has the chance to influence future business leaders because that’s who our students are,” says Sellers.

Addressing sexual violence/setting healthy boundaries

The Kinsey Institute is also working with a younger audience. Since 2019, about 5,000 Indiana rural school students, parents, and educators have participated in an IU Center for Rural Engagement and Kinsey Institute program on setting healthy boundaries, both online and off. A 2021 Indiana Department of Health survey revealed that in 2011, 14.5 percent of female Indiana high school students reported having been forced to have sexual intercourse, and by 2021 that number increased to 16.8 percent.

Zoë Peterson is a Kinsey researcher and professor who helped develop the Healthy Relationships for Rural Youth Initiative with Catherine Sherwood-Laughlin of the IU School of Public Health. | Courtesy photo

Zoë Peterson is the director of Kinsey Institute’s Sexual Assault Research Initiative. As a clinical psychologist, researcher, and professor who has worked extensively with college students, she knew she could help in educating students about setting healthy boundaries through a program in elementary and high schools.

“We wanted to in some way show/address sexual violence and promote healthy relationships among youth,” says Peterson, who along with clinical professor Catherine Sherwood-Laughlin of the IU School of Public Health, reached out to schools in rural communities such as Orange County and found a positive reception.

Now a clinical therapist with Thrive Orange County, three years ago Brandy Terrell was a social worker with Orange County Schools, and she helped open the door for the project in the elementary schools. Terrell knew that pregnant women in the county had a high level of adverse childhood experiences (ACE) and with a high ACE score comes poor long-term health outcomes. She found the high ACE score was also true for Orange County elementary and high school students. So she promoted the potential partnership and worked with religious leaders, school superintendents, parents, and teachers to develop a healthy relationships program that includes social media concerns. Parents of a French Lick church youth group that took the course were most enthusiastic.

“A lot of parents — myself included — have a really hard time keeping up with social media trends and safety, so it’s a much-needed program,” says Terrell.

John Leman, research coordinator for the Healthy Relationships for Rural Youth Initiative, presenting at the Indiana School Safety Specialist Academy. | Photo by Benjamin Maddock

Though Peterson’s team initially thought the communities would prefer reaching high school students, soon they were creating material for first-graders, using age-appropriate techniques.

“We use examples, such as ‘Your friend is tickling you and it’s not fun anymore’ and those kinds of things,” says Peterson. “It’s [more] like healthy-relationship education rather than sex education, although it certainly has lots of implications for future healthy sexual relationships.”

A group of graduate students in various fields such as psychology, counseling, and public health teach the school programs, which are part of the Healthy Relationships for Rural Youth Initiative developed by Peterson and Sherwood-Laughlin. It is funded through a service grant from the Indiana Department of Health and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Peterson says she hopes to obtain a research grant to conduct more data-driven analysis of the success of the program.

Scholarly concentration in med school

Another of Kinsey’s newer initiatives is with the IU School of Medicine. When students apply to medical school, they may also apply to a scholarly concentration in human sexuality and health, started in 2020 by the Kinsey Institute’s Assistant Director for Education Jessica Hille. Students complete two three-week courses in the summer after their first year of med school and work with a researcher on a project that results in a paper they can submit to a scholarly journal. Three students have already completed papers, including one by Keeley Newsom, a fourth-year student who conducted a survey of LGBTQ+ patients and how they are treated in medical situations. From this came the article “They ‘Don’t Know How to Deal with People Like Me’: Assessing Health Care Experiences of Gender Minorities in Indiana,” written with Michael J. Riddle, Gregory A. Carter, and Hille.

(top) IU medical student Keeley Newsom. (bottom) Jessica Hille, assistant director for education at the Kinsey Institute. | Courtesy photos

Newsom, who was in the first group of students enrolled in the scholarly concentration, found the small cohort of six or seven students invited more discussion and collaboration.

“It felt nice to find a niche within medicine where you have folks who are striving for the same things,” says Newsom. The group could “bounce a lot of ideas off each other in class.”

Ultimately, those discussions encouraged them to get funding for a Bloomington clinic dedicated to LGBTQ+ patients, expected to open in fall 2023.

“It’s been a lot of work to get it off the ground — funding and whatnot,” says Hille. “But they’ve been very dedicated, and in addition to my role with the concentration I’ve been an advisor for the clinic.”

While Newsom won’t be able to work at the clinic — she’ll be off to her expected residency in plastic surgery — she’s happy to see it will be sustained. “What’s nice about this concentration is that it provides a kind of a constant inflow of students who are interested in providing this sort of care,” she says. “Every year between six and twelve students are going to be joining this concentration and carrying on the work in the foundation that we’ve laid down.”

The students’ intended medical specialties vary from psychiatry to public health to obstetrics and gynecology, says Hille. Fifteen students have already completed the coursework and are on track to finish their papers.

“We’re just really proud of and impressed by how engaged the students are and how interested they are in the material,” says Hille. “They are still in formal medical training, and there isn’t a lot specifically on gender and sexuality issues, so to be able to talk to them about that and then they take these conversations back to their friends and colleagues in the medical schools is great.”

Zhou, the Kinsey library director, expresses optimism for the institute’s future. “We are not an advocate organization, but learning about rights and of our sexual being is important. Every new generation comes to their own sense of selfhood, and we can allow that new start to be better and brighter than the generation before.”

The Indiana Legislature

On May 10, 2023, Justin R. Garcia, executive director of the Kinsey Institute and Ruth N. Halls professor of gender studies at Indiana University, wrote an article for the Washington Post (paywall) about how Indiana lawmakers approved a budget that specifically blocks IU from using state funding to support the Kinsey Institute.

Gov. Eric Holcomb signed a law that “takes aim at the very foundation of academic freedom,” Garcia wrote. He also noted that the institute has been the target of attacks since it was founded in 1947.

Lorissa Sweet, a freshman Republican from Wabash, had proposed the legislation that, Garcia wrote, “parroted false allegations of sexual predation in the institute’s historical research and ongoing work, which the institute, the university and outside experts have repeatedly refuted.”

Garcia went on to quote Indiana state Rep. Matt Pierce (D–Bloomington), who described the conspiracy theories as “warmed-over internet memes that keep coming back.”

—Limestone Post