My parents lived in small-town Indiana. Five years ago when my father was diagnosed with stage 4 pancreatic cancer, he had to travel more than an hour to receive care multiple times a week. Because my mother had advanced-stage Alzheimer’s disease, finding care for her was difficult, and the local nursing facility was, as we discovered, unequipped to handle her care. Their small town had no hospital or cancer care facilities. It had no specialized Alzheimer’s disease facilities. So my family’s question became how we manage both parents’ care in a place lacking care for their conditions. We couldn’t. Like so many who live in rural areas, my family had to make hard choices that ultimately meant that they had to leave their home of more than fifty years to get the care they needed.

In the United States, 46 million people live in rural areas — 20 percent of the U.S. population living on 97 percent of its entire landmass. Rural healthcare has long been on the precipice. According to Tara Hatfield, president-elect of the Indiana Rural Health Association, the most common misconception is it is “less advanced or innovative than the care one would receive at an urban hospital.” While one can argue that rural healthcare is as advanced and innovative as urban healthcare, the fact is no long-sustaining solution has been modeled in the states. Problems still exist despite the fact that this populace — who regularly go without an emergency-room or intensive-care unit in their community, or even without primary care physicians, along with other specialty services — needs help.

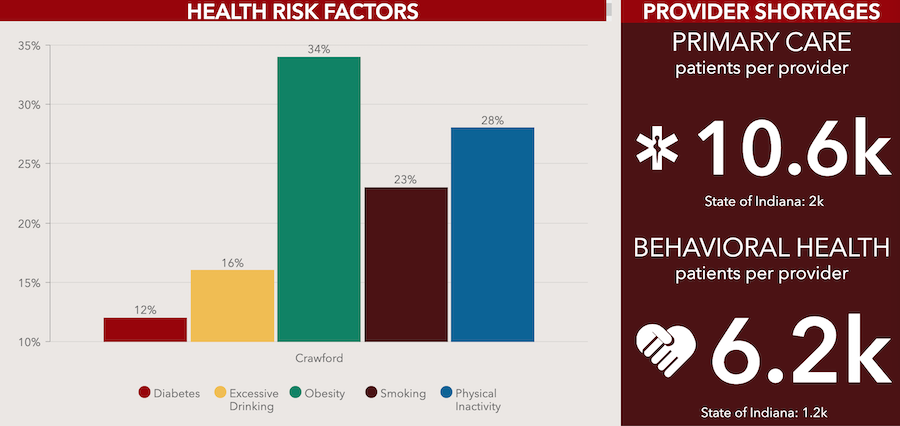

The Indiana University Center for Rural Engagement and IU School of Public Health have worked with leaders in several southern Indiana counties to examine the health needs of their communities to devise Community Health Improvement Plans (CHIPs) and help to address those needs. Above is a screenshot of the dashboard for Crawford County, showing its top five health needs and number of patients per provider for primary care and behavioral health services. More counties can be found here.

According to the Rural Health Research Gateway, people who live in rural areas are at higher risk for chronic disease, obesity, substance abuse, and mental health illnesses. They live in food-insecure areas with transportation and housing problems. They are an aging population who face poverty and no health insurance. And many communities offer few opportunities for exercise and recreation. Counties also face sparsely staffed health departments to monitor overall health. Recently, Indiana University’s Center for Rural Engagement found that the most significant health threats reported by southern Indiana counties are chronic disease (reported by 80 percent of the counties), substance abuse (70 percent), and mental health issues (60 percent). Access to healthcare is also one of the biggest health threats.

So, imagine having a stroke in a small town with no hospital. For instance, Martin County has no hospital. According to the Centers for Disease Control, the key to successful stroke treatment and recovery is getting to the hospital quickly. For stroke victims to obtain life-saving treatment on the way to the hospital, the CDC recommends that stroke victims use emergency medical services.

But in small towns, emergency medical services often operate in multiple areas or counties and may have to travel a signifiant distance to reach that stroke patient. They also frequently depend on volunteers to meet those needs and are sometimes unable to staff emergency services adequately.

Lack of medical facilities

In the U.S., approximately 45 million people do not live within one hour of a Level I or II trauma center. Here in southern Indiana, the current Indiana University Health Bloomington Hospital operates a Level III trauma center, though this will change when the new hospital includes a Level II trauma center. Throughout the U.S., trauma care centers in hospitals are designated by level, Level I, II, III, IV, or V, and categories can differ from state to state. A Level I trauma care designation is the highest level of surgical care available for trauma patients and requires an organized teaching and research effort for trauma care. This teaching and research aspect is not required in other trauma care levels. In all levels, 24-hour immediate emergency room, surgical, and other specialty coverage is required and the level designation is dependent on the type of immediate care services that are provided by that hospital.

Many rural residents in southern Indiana do not live within one hour of a Level I or II trauma center, Rebecca Hill writes. The current Indiana University Health Bloomington Hospital operates a Level III trauma center, though this will change when the new hospital will include a Level II trauma center. | Photo by Limestone Post

According to a report by The Chartis Group, rural communities have fewer than 6,400 ICU beds, or one ICU bed for every 9,500 Americans. But as a stroke patient, your survival and recovery depend on speed and access to ready emergency services, so if you don’t have it, your chances are limited.

Now replace the word “stroke” with any other trauma incident or chronic disease like diabetes, heart attack, cancer care, or even an injury from a farming accident. Inadequate funding and the lack of services and personnel threaten a rural healthcare system overall. While many of us take having a hospital or a hospital emergency room for granted, approximately 16 counties in Indiana do not have a hospital. You may have only a rural outpatient health clinic or a critical access hospital (hospitals with 25 or fewer acute-care beds), or you may have nothing.

According to Chartis Center for Rural Healthcare, 120 rural hospitals closed across the nation from 2010 to 2019, on the average of about 12 per year. However, the number in 2019 topped at 19 rural hospitals closed, a significant increase from previous years. Currently, rural Indiana has 35 critical access hospitals and 77 rural health clinics (providing outpatient primary care services) for 92 counties. While losing a hospital dramatically impacts a person’s ability to get care, a hospital closure can severely impact the community. Hospitals are often the only, or one of the largest, employers. When Kentuckiana Medical Center in Clarksville closed in April 2019, its 269 employees were laid off.

Pandemic stress on hospitals

The COVID-19 pandemic has stressed rural hospitals even more. The American Hospital Association estimates that hospitals nationwide lost $353 billion in 2020 and that 453 rural hospitals (nearly 25 percent of all rural hospitals) are vulnerable to closure. The NC Rural Health Research Program found that Midwest rural hospitals have a higher percentage of patients with COVID-19 than urban hospitals. Plus, they hospitalized more COVID-19 patients, many of whom needed specialized services like ICUs or respiratory care.

Cara Veale, the CEO of Indiana Rural Health Association, says, “Financial stability is a key challenge” to rural hospitals. | Courtesy photo

Healthcare infrastructure has long been in an economic free fall. According to Cara Veale, the CEO of Indiana Rural Health Association, rural hospitals consistently face funding obstacles. “Financial stability is a key challenge,” says Veale. “Before COVID-19, many rural hospitals were operating financially in the red.” Another obstacle, Veale says, is that many hospital facilities are aging and need major infrastructure updates. So how do rural hospitals find the funding?

Because Indiana is a Medicaid expansion state, studies reflect that rural hospitals may fare better than those in non-expansion states. Research has consistently shown that Medicaid expansion improves a hospital’s ability to stay afloat in typical times because it reduces the amount of uncompensated care they must carry on their books. Having the backing from a more extensive health system, say like IU Health, can also make a difference between failure and survival.

For rural residents, having health insurance is critical, but it is also essential for hospitals. Since its enactment in 2010, the Affordable Care Act has reduced the number of uninsured residents in rural areas, so a rural hospital carries less uncompensated care on its hospital books.

Now with COVID-19, funding issues have become even more complicated, says Veale. “Many rural facilities moved entire service lines to make space for quarantined patients and equipment, and patient rooms were upgraded to ensure hospitals were able to care for COVID-19 patients.” Just as postponing elective surgery and closing physician offices strained hospitals, so did things like having to buy more ventilators and personal protection equipment and having limited healthcare personnel available.

Doctors aging out

The recruitment and retention of healthcare providers is another thorny problem for rural health communities. In my parent’s hometown, two doctors served a town of more than 2,600 people. When both of those doctors retired, it left the community without a doctor. The aging out of a community’s physicians is not uncommon in rural areas.

Right now, Indiana has 231 practicing physicians per 100,000 people, with 31 percent age 60 or older. The issue of physician retirement and replacement is a continued problem. In fact, a New England Journal of Medicine study found that by 2017, more than half of the physicians in rural communities like my hometown were at least 50 years old, and a quarter of those physicians were at least 60 years old. Whether this gap can be closed depends on the type of incentives or programs that a state employs to encourage physicians to invest in rural medicine.

Across the nation, communities have employed programs like physician loan repayment or national health service corps expansion. Programs in Indiana include the Indiana University School of Medicine’s Rural Medical Education Programin Terre Haute and its Project ECHO programs, which focus on getting providers involved in rural medicine. Even scholarship programs like IU’s Indiana Primary Care Scholarship Program can make a difference.

Tara Hatfield, president-elect of the Indiana Rural Healthcare Association, says the most common misconception about rural hospitals is that the care is “less advanced or innovative than the care one would receive at an urban hospital.” | Courtesy photo

But despite these efforts, newly licensed physicians are not flocking to the rural countryside. Maybe one reason is that rural medicine is not considered a medical specialty but a geographical problem.

“My biggest soapbox about rural health is that it is a true specialty just like any other specialty,” says Hatfield, of the Indiana Rural Healthcare Association. Refocusing the medical school curriculum to include rural rotations or residencies and other rural training or curricular elements may change this. Still, time is of the essence. The New England Journal of Medicine projects that by 2036, rural area residents will have access to only one-third of the physicians per capita than residents of urban communities will have.

To solve the physician shortage, rural communities have taken advantage of nurse practitioners (NPs), physician assistants, and even telemedicine to fill those gaps. As of 2019, some 5,330 nurse practitioners worked in Indiana, though only 250 NPs served in southern Indiana as of May 2019, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Of the mere 1,530 physician assistants working in Indiana, only 60 served southern Indiana as of May 2019. To practice in Indiana, NPs must form a written supervisory agreement that identifies how the NP and physician will cooperate, coordinate, and consult with each other. Physician assistants must also have a written supervisory agreement that includes all the physician’s tasks and protocol for prescribing drugs and other duties. Because I could not find a doctor for myself when we moved to Bloomington recently, I became a patient of a nurse practitioner who provided me with the same care that I would have gotten from a physician.

Telemedicine expands access … to some

Liked by nearly all patients, telemedicine has been a boon to primary care services, especially in rural communities and now during the pandemic. Before COVID-19, providers did not universally adopt telemedicine, and on many healthcare agendas it was a “to-do” item.

But with COVID-19, virtual health visits spiked with the closing of physician offices and the limitations imposed by hospitals and rural healthcare clinics. Last spring, during the lockdown, the IU Student Health Center provided telemedicine for students on lockdown. They reached students who resided in Indiana, but they could also offer telemedicine services to students who returned to five other states, according to Pete Grogg, executive director of the center. They provided telemedicine not only for medical issues but also wellness counseling and mental health issues.

“We were able to transition to telemedicine within a week after we were shut down,” Grogg says. “While students typically prefer in-person visits, they appreciated the opportunity to have these services too. We were glad that we could stay in touch with our students and continue their care.”

In some places, like South Dakota where emergency services are extremely limited, telemedicine has supplanted traditional emergency rooms. There, a telemedicine center assists emergency-response care, using remote-controlled cameras, computer screens, and available providers to evaluate emergency care cases.

In rural areas, before COVID-19, Medicare coverage for telemedicine covered patients under limiting circumstances. The patient had to be physically present in a healthcare facility during calls. Telemedicine providers needed to use approved technological platforms, and the provider had to be eligible for coverage.

But the 2020 CARES Act loosened restrictions, allowing telemedicine visits regardless of where they originated, and allowed services for reasons other than COVID-19. “Telehealth waivers allowed more services,” says Veale, “and allowed patients to receive remote care from any provider anywhere.”

But in rural communities, broadband access has been a challenge for using telemedicine. According to Pew Research, 24 percent of rural Americans say that having access to high-speed internet is a significant problem. In Indiana, 30 percent of the population has no internet access and use cellular data only. Of those with only a mobile device, 27 percent have no computer and use a cellphone only, which may prohibit telemedicine access. Provided patients had access to the necessary broadband for internet access, those limited by lack of transportation or even access to services could now get telemedicine. Telemedicine, says Veale, brought the providers to the patient, expanding their access to care.

‘Open to working together’

As community wellness coordinator at Purdue Extension, Ashlee Sudbury (above) works with four rural counties — Dubois, Martin, Daviess, and Orange — to help solve problems such as access and availability to healthcare. | Courtesy photo

Solving problems like access and availability have really become the crux of the problem for rural healthcare, says Ashlee Sudbury, community wellness coordinator at Purdue Extension. Sudbury works with four rural counties: Dubois, Martin, Daviess, and Orange. She finds that it can be challenging for a community to know where to start to solve these problems. “Every community is different, so every community’s experience is different,” she says. But rural communities are finding that they must come together to solve these issues. One solution is through community engagement and planning.

Professor Priscilla Barnes of IU’s Center for Rural Engagement believes they have hit upon a means to fix the rural healthcare problems of access and availability through its Community Health Improvement Plan program or CHIP. Barnes facilitates this program with her health liaison, Katherine Pope. Currently, they’ve completed CHIPs in Daviess, Orange, and Crawford counties, with five other counties in progress.

Under the Affordable Care Act, hospitals must create a community needs assessment every three years. In the evaluation, they must identify community health needs and create a plan for addressing those needs. For eight southern Indiana counties, the next step has been to use Barnes to help them start a CHIP for their county. Using an eight-step process with the data from the community health needs assessment, county CHIP teams seek data-based solutions to rural health issues.

Among Barnes’s first steps is to bring community people together to collaborate and cultivate partnerships that ultimately lead to an action plan that solves a specific community’s healthcare needs. In most communities, existing groups may be addressing those needs in some form but may not be aware of another group providing similar services. Or a group that provides one service — say, mental health counseling — may not realize their connection to other rural health problems, such as substance abuse. A CHIP is not limited to healthcare organizations only; some CHIPs incorporate input from groups like the YMCA, county council, city parks departments, or the school system.

Professor Priscilla Barnes, of Indiana University’s Center for Rural Engagement, says, “Most rural communities are open to working together” in the Community Health Improvement Plan (CHIP) program. | Courtesy photo

“Most rural communities are open to working together,” Barnes says. “But sometimes people don’t have clarity about the differences between these groups. It can get muddled. We need space to figure out what each other is doing so they can create a common space to work together.”

It’s the holistic approach that makes it successful. Say you have a heart attack. You go to the hospital and receive care. But what happens after? Does your community provide walking trails so you can exercise? Are there smoking cessation programs? A CHIP takes a holistic approach to healthcare. Why? “We need to have a new healthcare paradigm for how we look at health on the continuum, from everything needed when you are sick to how to keep you well,” Barnes says.

Another step, says Barnes, is the infrastructure. For instance, if one goal of the CHIP is to recruit more doctors, “it takes a collective group of community organizations to make it happen. The community defines [their need], so they can determine what resources are needed.”

For example, Decatur County looked at substance abuse in the creation of their CHIP. “I wanted to know who the existing organizations focused on substance abuse were,” says Barnes. “We didn’t want to duplicate efforts. We wanted to support those efforts.” Since most counties have a local coordinating council, says Barnes, the goal was to bring those organizations together to talk about how mental health is impacted by substance abuse and to discuss prevention.

As health liaison for the CHIP program, Pope puts it this way: “If we come together, we learn what each other is doing, and maybe if mental health and substance abuse people can work together, then we can leverage the resources together to be more effective.”

Maximizing community input and talent

For rural communities, leveraging resources is critical, especially in places without adequate funding resources. A CHIP can give partners a chance to pool their funding or seek funding by demonstrating their partnership to grantors. For instance, one of the greatest needs in the Daviess County assessment was transportation and housing.

Katherine Pope is a health liaison for the CHIP program. She and Barnes have completed CHIPs in Daviess, Orange, and Crawford counties, with five other counties in progress. | Courtesy photo

“You might look at it and ask, ‘What do housing and transportation have to do with healthcare?’” Sudbury says. This lack of housing and transportation puts a person at greater risk for long-standing health problems, says Sudbury. She believes that multiple vectors of the community have to be at the table to accomplish a more holistic approach, an approach that solves all the healthcare needs of county residents. Since most rural communities scramble individually for resources, these partnerships can avoid duplicity in efforts and funding, making it more economical.

When COVID-19 hit, many counties were surprised by this unexpected health crisis, though preparedness may likely be an additional element in the future. Sudbury found that many partners retreated into their silos despite having a CHIP underway with the pandemic. Still, they are better situated with the CHIP, says Sudbury. “In some communities I work with, I think that because they had worked on other things together in the past, it became more natural for them to communicate together about COVID-19 issues.”

In the end, the CHIP is a living document because we are never done with health improvement, says Pope. An adaptable CHIP plan means that it accommodates any unexpected health crisis a community faces. COVID-19 is now part of the coalition discussions, Pope says, because “COVID-19 is the biggest health issue that they are facing now.”

The question of rural healthcare seems an insurmountable problem even though there are multiple attempts to solve it. But a solution like a Community Health Improvement Plan appears to be a step in the right direction. For Barnes, it is about outcomes and what the CHIP is trying to change. “There is no front door to health,” she says. “Sometimes you go through a window, the back door, or the garage door.”

And that’s what CHIP is about — maximizing community input and talent and sharing resources to make that change by the people who need and use it. It’s not groundbreaking, but it is, for a populace that really needs it, a start.