Fresh out of college in 2007, at the request of the Indiana University Robotics Club, Adam Nahas made a robot hand in the basement of the townhouse where he lived.

“No ventilation,” he says. “No windows. It had a single staircase so I couldn’t bring any big equipment down there.”

That basement was his workshop. He was hoping to create a few small things — “craft stuff,” he calls them. After spending four years at IU, trying on different creative programs like so many spring jackets, he’d settled on working with metals as he embarked on his journey in what some of us like to call the Real World.

He knew he’d need more than a stuffy, dank basement for a workspace if he was going to make something of himself as an artist or an artisan. That basement may well have served as the inspiration for a grand, cooperative project Nahas started envisioning, a project that has evolved into Artisan Alley.

Nahas is the founder and executive director of the now-nonprofit Artisan Alley. His vision over the years has evolved into a three-location operation, including a tool-lending library; a complex of studios, classrooms, and exhibition spaces; an artists’ market; computer lab; meetings and seminars room; and an overall hub for local artists. Call it a one-stop resource for Bloomington’s creative community.

It came about, in the main, because Nahas and his friends from art school found themselves adrift after graduating from college. “Adam Nahas is an artist who makes his living by offering resources and creative services to other artists in addition to selling his own work,” writes cabinet-maker Nancy Hiller in her blog, Making Things Work.

Artisan Alley’s location at 222 W. 2nd Street includes event and classroom space, a computer and co-work lab, Dimensions Gallery, and a market where artists can sell their work. | Limestone Post

“It started as one thing and slowly became something totally different,” Nahas says. “It started off as just a group of kids that, right after college, didn’t have the resources that the college provided anymore. We all started getting jobs but we still had that desire to be part of a collective or part of a group.”

Nahas, speaking about young artists fresh out of college, told an interviewer in 2017: “The moment you leave school you’ve got to start all over.”

A bronze sculpture that Nahas was originally commissioned to make as a gargoyle for a limestone company. | Limestone Post

At IU, Nahas and his pals had access to a treasure trove of workspaces, tools, equipment, paints, brushes, sculpting implements, frame-making facilities, soldering irons — anything any artist might need to produce the next great work. The day after graduation, all those resources became off-limits.

“In college, you’ve got this network of new, excited artists that are all generating ideas, and you thrive off of that,” Nahas says. “You’re surrounded by great instructors trying to teach you new processes. You’ve got amazing resources: individual locations that focus on those processes, whether it’s printmaking, screen printing, sculpture, jewelry, painting, photography. All that stuff is right at your fingertips, and then when you’re done paying your tuition and you walk away from school, you’re left with the debt and a lot of knowledge.”

Young artists trying to work in their chosen fields, Nahas argues, need a lot more stuff to be able to thrive than, say, business majors do. “You still need those resources. You need those physical things that you have to reinvest back into. There are definitely some programs in college that, when you’re done, the education and a laptop are all you need. But definitely in the fine arts and the humanities, you’ve got to rebuild that infrastructure to continue to move forward.”

Nahas had scored an internship with Owen County sculptor Mark Parmenter while still at IU. Parmenter ran his own bronze-casting foundry.

“I did that for a year. I was learning the mold-making process and life casting and modeling, doing all the things a sculptor would do.”

The internship harkened back to earlier days when kids learned trades under grizzled veterans as apprentices. “Exactly!” Nahas says. “That’s what I was. The old medieval Guild style.”

The internship ended after a year. Nahas loved the work and Parmenter was pleased with his pupil. So Nahas asked Parmenter if he could stay on.

Twisted Lounge (800 W. Kirkwood) provides members of Artisan Alley with office space for meetings and seminars. | Limestone Post

“He goes, ‘Yeah. You’ve learned so much and you had a year where I didn’t pay you anything, so I’d actually be willing to pay you.’

“I said, ‘Oh my god! That’d be great.’”

So began a long working relationship between the two.

“I worked with Mark for eight or nine years,” Nahas says. “A couple of years into working for him, me and some of my college friends said, ‘Hey, wouldn’t it be great if we brought things back together? If we had a place to work out of?’ At that time, I was doing the side projects out of my basement. It would have been a great advantage to have more space. To be able to collaborate would have been a huge asset to me.”

The little gang of artists, seven of them, began making plans. “We reached out to our friends and said, ‘Hey, do you want to go in on this idea where we all split rent on a dilapidated building?’”

Artists are generally not known as the savviest of businesspeople, so Nahas and the gang went in on an old fire extinguisher company-slash-plumbing-business building. Even though the structure was not something a real estate trader would jump at, Nahas used a lot of the lessons learned from Parmenter to elevate the business sense of his new partners. Artists often like to think they’re above business; Nahas did his best to disabuse them.

“Business is a totally different hat you’ve got to put on,” Nahas says. “You can be a craftsman all day long, but if you can’t market yourself, if you can’t do the business side of it, you’re never going to get your work out there.”

Technically, Nahas was a contractor to Parmenter, not an employee. “That’s how I started learning how to be an independent contractor, invoicing him, and learning that side of things, which is something you don’t learn in college. You learn how to be an employee.

“Mark was a great mentor to me. He taught me the business style that I didn’t get being in an arts school. Maybe if I would have taken some classes at Kelley [School of Business at IU], that would have been different.”

Jeanne Smith (left) spoke with Nahas at Dimensions Gallery as she prepared for her show, “Bikes to Boudoir — Gender Queer Transition to Tactile Expression,” a look at her life’s work, which opened August 2. | Limestone Post

That gang of artists, by the way, was a mixed group. Nahas’s meanderings early on in college put him in contact with artists from a wide range of disciplines. “My friends weren’t all the same kind of artists,” he says. “I jumped around in college, so there was a music guy that I met when I was singing at IU and there was a dancer who I met when I was on the performance side of things, there were the fine artists I met through art history classes and studio classes. There was a painter, a graphic designer, a web designer, a writer, all that kind of stuff.”

The bunch of them settled into an old warehouse across the street from the Twin Lakes Recreation Center softball diamonds. It had a bare concrete floor from when it was home to a fire extinguisher outlet and plumbing business. The seven called themselves Blank Canvas.

“We rented it out for two years. It was more of a clubhouse. It wasn’t really open to the public. It was just a place we went to work. We had the musician in the small office, the graphic and web designers shared the front room, as it was carpeted and a bit more finished, the writer and painter shared another large room, I ran the tool studio and had my sculpture workshop there, and the back room we laid new flooring down so the dancer could use it to practice. We all knew each other, we all trusted each other. We had Halloween parties, very artsy. And then it all had to change.”

The City of Bloomington bought the property for some infrastructure improvements in 2009. Nahas’s artist collective had to move, quickly. “That was really disheartening,” he says.

He sought out advice from then-assistant director for the arts in the city’s department of economic and sustainable development, Miah Michaelsen.

“She told me, ‘If any of you guys are actually a business, you could apply to get a city moving grant.”

(left) One wall of the Burl and Ingot Tool Library (1305.5 W. 11th St.), an industrial arts workspace and artist studio with a tool-sharing library that includes hand and power tools and other heavy-duty equipment, such as air compressors and a ceramics kiln. (right) Nahas is interviewed by WTIU outside of Artisan Alley next to the B-Line Trail. | Limestone Post

Thanks to Parmenter’s mentoring in arts entrepreneurship, Nahas had already set himself up as a business. “He showed me how to be an independent contractor,” Nahas says, “invoicing and learning that side of things.”

Nahas’s business applied for the moving grant and was awarded $5,000 to relocate. “Some of us split from the collective,” Nahas says. “The graphic designers, the web designers, those who could work from home were like, ‘Aw, I really don’t want to keep this going.’

“The other half of us — the writer, the painter, myself — were like, ‘Let’s keep this going. Let’s invite more artists into it and make it more of an arts thing rather than a private thing.’”

Under Nahas’s business aegis, the collective used the moving grant money to cart off all their stuff and pay a month’s rent and deposit on a building toward the north end of the B-Line Trail. “A lot of people know that building now as a yoga studio. It’s been muraled and it’s blue and green and red,” Nahas says. This iteration was called Trained Eye Arts Center.

“That’s when we were trying to formalize,” Nahas says. “We were like, ‘We should make this a thing. We should invite other artists. We should get musicians.’ That kind of thing.

“It slowly became more of a cooperative where we all had different roles and responsibilities. Since I had the most experience as a contractor, I handled a lot of the contracts and the finance and the governance. Our graffiti artists and our painters, they handled the beautification; they would do murals and things like that. Our web designers and graphic designers helped get our website up and documenting our events. It just kind of grew from there.

Jerrold J. Willis runs JW & Company Barbershop, one of the original tenants of Artisan Alley’s 2nd Street location. | Limestone Post

“We turned the original idea into something a little bit better. We started doing art shows and things like that and it all evolved from there.”

Nahas kept in contact with Miah Michaelsen. “She pointed us in the right direction, gave us a few inside tips. She’d say, ‘Hey, you should check into this’ and ‘Look into that.’ She really guided us on this path to become where we are right now as Artisan Alley.”

Michaelsen now is the deputy director of the Indiana Arts Commission. She still lives in Bloomington.

Nahas and company kept Trained Eye alive for two years. But by the end of that time, the arts center was on life support.

“The Trained Eye Arts Center had to end because our location wasn’t really working out for us,” Nahas says. “We wanted a longer-term agreement but the landlord wasn’t willing to provide that. Then the job that I had at Mark Parmenter’s foundry came to an end. He was in his 70s and he was ready to retire. I couldn’t maintain the Trained Eye Arts Center without a full-time day job. We didn’t quite have it as a sustainable organization. We were all trying to pitch in. I was trying to rent out space, so if we didn’t have a space rented out, I had to compensate for that.”

Nahas took a job at an art foundry in California, hoping to help keep Trained Eye up and running from afar.

“That didn’t work out,” he says. In retrospect, he feels he was really the sole driving force behind the center. Without him in town, the center fell behind on things like maintenance and event scheduling.

“I now realize I was that guy who was pushing everybody to kind of grow and develop. Without me here pushing, it just didn’t quite keep going. It kind of fizzled out.”

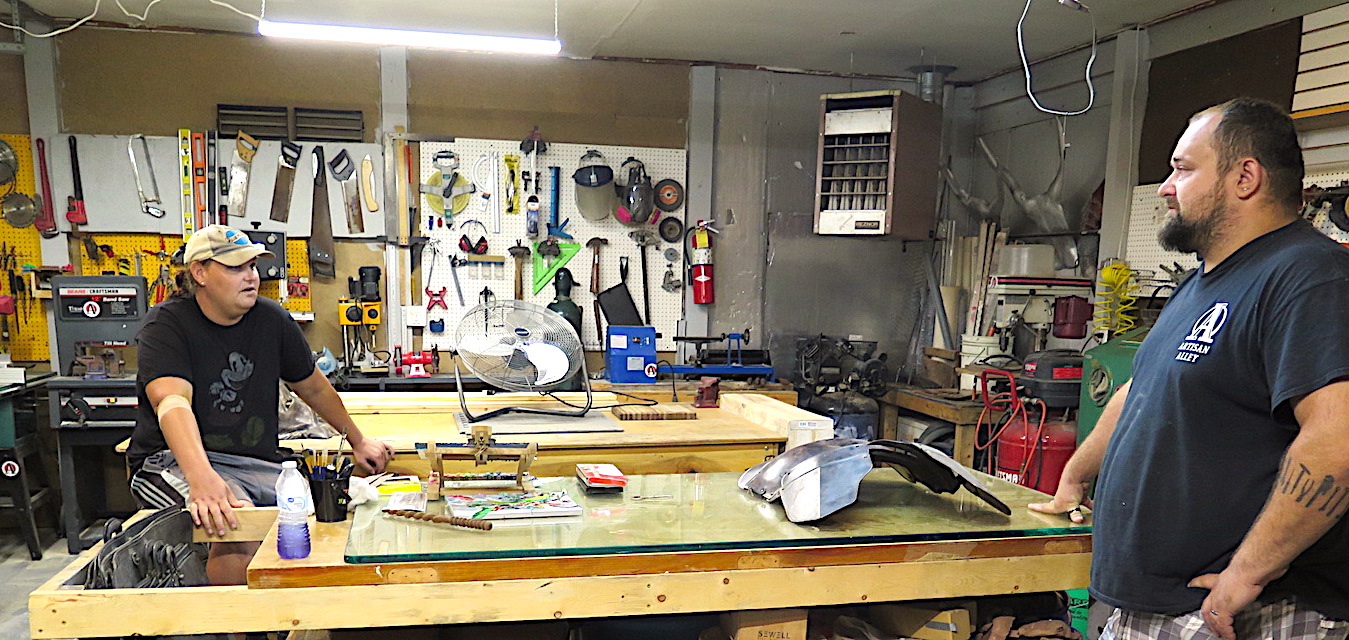

Artist Brandi Wampler (left) and Nahas in Burl and Ingot. | Limestone Post

Nahas returned to Bloomington after six months or so to help with a family member’s illness, as well as to right the sinking Trained Eye ship. His time on the West Coast wasn’t for naught, though.

“While I was out in California, I learned about all these cooperatives and co-work spaces. That was really new at the time. This was the early 2000s. So I was like, ‘Why don’t we try to do something like that here?’

“They have this great thing out in the San Francisco Bay area called The Crucible. It was all these industrial artists like glass workers and metal workers all working in one space as a creative center.

“I took a lot of those ideas and brought them back to Bloomington. I reached out to Miah Michaelsen again, and said, ‘Hey, do you have any spaces that I might be able to get this going again?’”

This was five years ago. Michaelsen pointed Nahas toward a couple of structures in what was to become Switchyard Park. Park planners at the time didn’t know what to do with the buildings until they were to be razed (that happened in 2018). So Nahas rented them and the structures became the home of Artisan Alley.

“I started up again, just as myself without the collective,” Nahas says. A dozen or so friends and volunteers eventually came aboard, and the collective idea was reborn as Artisan Alley. “It felt like Artisan Alley embodied what we were trying to do. We were starting to venture out beyond just artists. We were looking at other people that do things with their hands.”

Now, Artisan Alley boasts three paid staff members, 10 volunteers, and more than 50 members working at the three locations.

Like Nahas himself, Artisan Alley is many different things. First Nahas. Here’s a list of jobs and/or accomplishments he’s done in his life:

- Sculpting contractor

- Metal worker/welder

- Started his own rental company

- Started a nonprofit

- Taught swing dance

- Art tutor

- Actor

- Singer

- Krampus Krewe contributor

- Co-founder, Trickle Down Effect comedy improv troupe

- Volunteer, Bloomington Township Fire Department

So it is with the latest incarnation of Nahas’s arts community locus. Here’s a list of what Artisan Alley has to offer:

- The Burl & Ingot Tool Library

- Workshop space

- Events space

- Rentable classroom space

- Creative arts classes

- Twisted Lounge (a space for meetings and seminars)

- Computer lab

- Co-work lab

- Community Market (where artists can display and sell their work)

- Dimensions Gallery (exhibiting local and visiting artists)

- Rental spaces (event venue, private studios, industrial studios)

And Artisan Alley’s first annual summer camp — three sessions each for kids and teenagers to learn and create a variety of art forms — began in June.

“I am an entertaining individual,” Nahas writes on his LinkedIn page, “willing to do what it takes to bring people together.”

He presides over the marriage of art and commerce in this town. As he told an interviewer in 2017: “We are trying to simplify the business of being an artist.”

[Editor’s note: Michael G. Glab’s full interview with Adam Nahas can be heard on his radio show, Big Talk, which runs on WFHB (91.3 FM, 98.1 Bloomington, 100.7 Nashville, 106.3 Ellettsville) every Thursday at 5:30 p.m. and is available, along with podcasts of past shows, at WFHB.org. Each of Glab’s “Big Mike’s B-town” profiles for Limestone Post is based on one of his Big Talk interviews.]