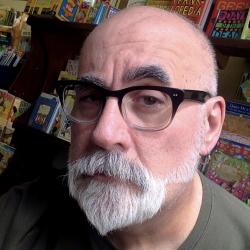

“Everything inside me — starting with my name, Vauhxx — spoke to me and said I had to speak up,” says Vauhxx Booker, spokesperson for Bloomington’s Black Lives Matter. | Courtesy photo

Vauhxx Booker is big on history.

“My history is definitely dictating my future,” he says. Booker is well-versed in his family’s — and his people’s — past. That past is compelling him to consider a run for political office this coming year.

History is one of Booker’s fortes in the trivia tournaments he likes to play in around town. History is something his family cherishes. They have plenty of it.

“I had a great-great-grandfather who fought in the Civil War,” Booker says. “He had come from Louisiana. He was born free. Louisiana had a three-tiered society: You had whites, you had land-owning free blacks, and you had slaves. He was a light-skinned Creole guy who fit into that middle caste. He went to Oberlin College in Ohio; it was one of the first colleges that educated Negroes. There, he met his future wife. They moved to Seymour, Indiana, and our family’s still there.”

Many of us — me, for instance — don’t know much of anything about our families beyond our parents and grandparents. Yet here’s the scion of a family that’s had roots in south-central Indiana for more than 150 years.

“We care about our families,” Booker says. “We take the time to preserve our history.”

The “we” in the preceding paragraph are African Americans.

They are his anchor. His foundation. A fellow like Vauhxx Booker walks into a room and even if no one has ever met him, they know something about him. It’s as clear as his skin color. But what do they really know?

If they’d care to listen, Vauhxx’d be happy to tell them about himself and his tribe. “I am a co-council member of Black Lives Matter and I serve in the capacity of spokesperson, as well,” he says.

“It’s a complicated story. I joined Black Lives Matter about two years ago when it was simply a Facebook group here in Bloomington. After being in that group for a little while, I noticed that there didn’t seem to be any black people!” he explains.

“I posted a comment: ‘Is there any black leadership?’ The moderator at the time responded that they didn’t have any black leadership. I said, ‘Well, I would like for you to make a post asking for some type of leadership, and if no one else steps up, I will take that duty.’”

And thus began Vauhxx Booker’s journey to becoming one of the most famous black people in Bloomington. He’s not the leader, in the familiar sense, of our local chapter of BLM, because the loosely bound organization doesn’t have a traditional hierarchy.

Or, wait — really they do. BLM chapters from here to either coast are modeled after a tradition that makes many other American traditions seem as venerable as the latest Queen Naija hit.

“Instead of sticking with a Eurocentric model of having a president, a vice president, or some type of chair, we opted to go back to our roots, to go back to a more tribal tradition of having a council of leaders.”

So Booker doesn’t issue orders or delegate authority. He and the rest of his BLM co-council members mull things over and come to decisions by consensus. Sounds rather democratic. Perhaps quintessentially American. And how many Americans do you know can trace their families’ histories back not just to last century but to the one before that?

“It’s given me a large base in Indiana to consider home: this whole Bloomington area, Columbus, Seymour. It’s all home to me,” Booker says. “It’s given me a deep sense of community and commitment.”

Booker, in blue, marches with members of Black Lives Matter on April 5 to a city council meeting at City Hall to protest the purchase of a Lenco BearCat. The meeting adjourned early, shortly after the group arrived. | Courtesy photo

Since assuming the role of spokesperson for BLM in these parts, Booker’s found himself drawn into oh-so-public frays time and again. His picture’s been on the front page of The Herald-Times. A video of him in a scrape with a Bloomington Transit employee has been viewed on YouTube thousands of times. His name has become familiar to viewers of Indianapolis’s TV news broadcasts. Often when he speaks, it’s news. That’s ironic considering Booker had trouble expressing himself as a young child.

“Funny thing to talk about that,” Booker says. “I actually had a profound speech impediment. I did speech therapy from kindergarten through my senior year of high school.”

Vauhxx, left, with his father, Michael. | Courtesy photo

“I’m a little reserved,” he continues. “I’m not much on public spectacle. Even though I’m private, I try to act boldly. One of my favorite quotes is from Virgil: Fortune favors the bold. I try to move in that way.”

Even funnier, Vauhxx Booker should be the gabbiest soul around, if his very name is any indication. “The story of my name is the story of my identity,” he says. “My father was in Vietnam, in the Navy. Like a lot of black men, he fought for a nation that still didn’t recognize his full rights. He saw a lot of black families be separated in his time. That affected him. He said he wanted to make sure that his children [Vauhxx has two half-siblings and a step-sibling], if we were separated, we would have unique names so we would always be able to find each other. So, he chose vox, which is the Latin for voice, and then he adapted the spelling. My mother said she was absolutely not going to name her child Vauhxx, but he won out. Eventually, my mom said she would have felt wrong to name me anything else.

“The irony of being a child who’s named ‘Voice’ and not being able to adequately use mine has cemented the importance of my voice and its power in me. I will always lift it for causes that I find just.”

Take, for instance, the city’s purchase last year of a new armored vehicle from Lenco Industries. The BearCat, as it’s known, is operated by police SWAT teams around the country. It’s been employed in a number of hot spots where minority groups have stood toe to toe against authorities. And BearCats are used in war zones like Syria. To many, they’re a symbol of repression.

“It’s hard, in my mind, to reconcile how that vehicle can serve a purpose in small city Bloomington, Indiana,” Booker says. “As a black person, my mind instantly went to some of the atrocities we associate with the BearCat. We can talk about Standing Rock. We can talk about Ferguson. Folks who weren’t even familiar with what a BearCat was had seen these images of tear gas being launched from them, of water cannons being used against Native Americans in almost-freezing conditions. There’s a deep trauma that is associated with the vehicle.”

February 15, 2018. Mayor John Hamilton was to deliver his annual State of the City address at the Buskirk-Chumley Theater. Vauhxx Booker was there. A couple of BLM members stood outside passing out flyers reading “Just Say NO! To Militarized Policing.” The mayor began his speech. Within moments, Booker stood up. He held a megaphone brought in by an ally. He addressed the mayor, loudly. “You knew we were going to be here tonight,” he said, according to the IDS. “We don’t want a war machine in our streets.”

A few in the crowd began chanting “Black lives matter!” Others counter-chanted. Hamilton repeatedly asked to be allowed to finish. Eventually, he gave up.

Booker and friends had driven the city’s chief executive out of the house.

Booker, during a Black Lives Matter rally held on the Square in July 2016. The event was organized by local high school students. | Courtesy photo

“The disruption of the State of the City is a complicated thing,” Booker says. “A lot of folks felt we hadn’t reached out to the administration in advance. We had. Mayor John Hamilton and I were already Facebook friends so when we created the [disruption] event, I had invited him to it. So he knew it was happening. He wasn’t blindsided. At any time, he could have reached out to me. Some folks said we should have let the mayor finish his speech. We already knew what the speech was going to be. The Herald-Times had already provided us a copy of the speech. I knew what he was going to say. I knew it wasn’t going to be anything substantial or in-depth.

“The only way we were going to get the engagement that we needed was to say we’re not going to allow the status quo to continue unless you address this issue.”

A couple of months later, on a Wednesday evening in April, Bloomington’s city council gathered for a special meeting. On the agenda: what to do with the current IU Health Bloomington Hospital campus when the new hospital opens in 2022. Not on the agenda: the BearCat. Nevertheless, Vauhxx Booker was there and the armored vehicle was on his mind.

Council member Dave Rollo held the gavel. Rollo was aware of Booker’s presence and his intention to speak, again loudly, about the BearCat. Rollo warned the gallery he wouldn’t brook discussion of the vehicle. Those who wanted to, Rollo said, could come to the next week’s regular meeting. Nevertheless, Booker piped up, speaking out loud without being recognized by the chair. Rollo banged his gavel. Then he directed a Bloomington police officer to throw Booker out of council chambers.

“I knew he would eject me,” Booker says. “I knew they were talking about this purchase [the soon-to-be-vacated hospital site] worth millions of dollars in the interest of IU and the interest of the [city] administration. I knew that my black voice and, potentially, my black life, would not be worth those millions of dollars.”

The next day, The Herald-Times carried a front page picture of a white police officer escorting Booker out.

“What went through my mind was the safety of the people I was with. I could have stood my ground. I could have had them physically remove me. I could have been arrested. But the question was really ‘How would the audience react? How would the supporters react?’ Would they, in concern for me or outrage, have acted out? Would anyone have been hurt?

“What we’re doing is we simply care about human life. So in that moment, it was important that I comply. I did tell the officer not to touch me. I said I will leave willingly. He didn’t touch me. I walked out with the police officer and the group followed me out as well.”

Jump ahead another couple of months. A drizzly June day. Booker went to the Bloomington Transit Center at 3rd and Walnut to buy a bus pass. He paid for it and left the building. He hadn’t walked far from the place when he heard someone shouting. He turned around and saw the transit ticket agent waving and hollering.

Booker’s family has had roots in south-central Indiana for more than 150 years. Pictured here are his great-grandparents Tillie and Everett. | Courtesy photo

“I thought she was saying I had forgotten my debit card or something,” Booker says. “But she accused me of having stolen a bus pass. Once again, my least favorite thing — public spectacle — broke out. I decided I should start recording the incident. I pulled out my phone, I showed her my bank account. I showed her that the transaction went through. She adamantly demanded that I let her copy my debit card.”

Booker refused her demand. She called the police. Many black people become awfully nervous when the police arrive on the scene.

“We’ve seen these situations play out all over the nation, where you have black people who are breathing and some white person who finds that offensive,” Booker says.

“To be a black child, even when we’re taught black history in the schools, what we’re really doing is rehashing the history of our oppression and our communal trauma. Folks often remember Dr. King in the ‘I Have A Dream’ speech in front of the masses. Black folks remember Dr. King locked in the Birmingham jail and people like Congressman John Lewis having their skulls fractured. Policing in America is a history of racial oppression.”

The situation was quickly de-escalated after Booker introduced himself to the responding police officer and she said ‘I know who you are, Mr. Booker.’ Booker says the transit agent seemed to retreat at that point. Booker went on to meet with city officials and Bloomington Transit’s general manager, Lew May. The discussion? Why did this happen and what can be done to prevent it from happening again?

“I had time to calm down from the moment and see things from her point of view,” Booker says. He then asked May not to release the agent’s name to the public even though she was to be fired for her actions.

“My life, in a lot of ways, has been defined by police interaction. As a child, I was accused of striking a teacher, an older lady who had said some things to me that were racist and who struck me. I was taken as a nine-year-old. I maybe weighed 80 pounds. I was shackled like a slave, by my hands and by my ankles, and they put a chain between the two. They threw me into a juvenile detention center. Luckily, I had parents who had the financial capacity and the community — a strong black church, a strong NAACP — that all came to my aid and rescued me from something that many black men in our society aren’t safe from.”

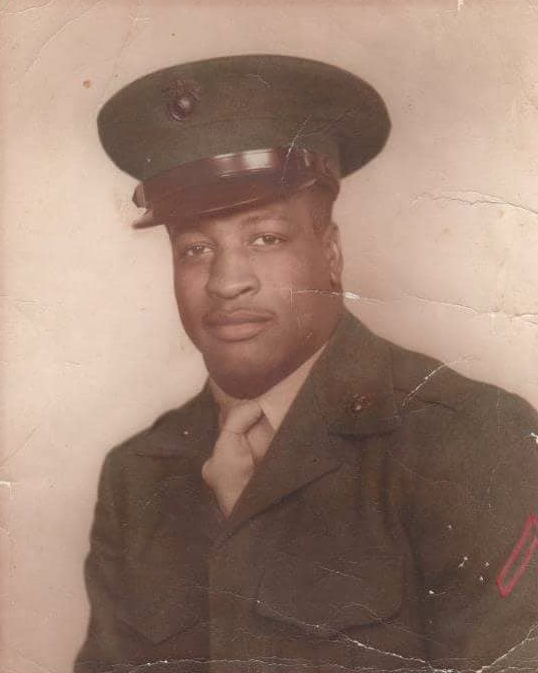

Booker’s grandfather Earl. | Courtesy photo

Booker was born and spent his early childhood in Columbus, Indiana. His mother, Annie (Rushing), was a teacher at the Atterbury Job Corps Center, his father, Michael, a union construction laborer. The Bookers lived, Vauhxx says, “a stable, middle-class lifestyle.”

He continues: “I was happy at home in Columbus. Three days before my 16th birthday, my mother passed away of cancer. She was a very strong, powerful woman. She made sure no one ever killed the fire in her child. I’m here today because of her. It’s always important that we recognize black women.”

Booker’s father was afraid he wouldn’t be home enough for his son, so he moved with Vauhxx to Seymour where the boy’s grandmother lived.

“I attended Seymour High School from my sophomore year to my senior year,” he says. “I did a lot of fun things. I was in marching band. I did competitive speech. And I just enjoyed small-town life.”

Booker and his father eventually moved to Louisville after Vauhxx had taken courses at Ivy Tech. (His father remarried after Vauhxx’s mother died.) Vauhxx never graduated from college but has thrived nonetheless. He worked as a security supervisor at Norton Audubon Hospital in Louisville. Then he wound up in Bloomington about a decade ago. He took a job as a rehabilitation specialist at Centerstone.

“I dealt with co-occurring mental illness and addictions, and often those folks were experiencing homelessness,” Booker says. “It was a tough job but I maintained a hundred percent housing rate, so I’m proud of it.”

Booker left that job in 2015. He’s now a certified nursing assistant. Oddly enough, he was on the verge of taking a job as a dispatcher for the Indiana University Police Department last June when the transit center incident occurred.

“I knew that taking such a public stance would cost me a job that was hard to get and that I was looking forward to,” he admits. “I was supposed to sign my final paperwork the next day.

“There’s always a price to be paid, but, at the same time, there’s always something to be gained. It’s been said that if you don’t speak out against your oppression, then folks will kill you and say you enjoyed it. Everything inside me — starting with my name, Vauhxx — spoke to me and said I had to speak up. I come from a people that have come too far and suffered too much for me to remain quiet.”

With everything bombarding us — from the news of extrajudicial killings of young black men to the everyday, seemingly small insults that black people must endure — it’s a wonder how a driven, involved activist like Vauhxx Booker can resist becoming enraged.

“I don’t have the luxury to do that,” he says. “I have to be aware of my position, that I’m a black man. The media will always love to portray me as the angry guy, the unreasonable guy. We saw that with the events surrounding Black Lives Matter. I need to maintain calm.

“We often see that police officers aren’t convicted because juries say, ‘Hey, this officer was in a tense moment that could be life or death. How could we expect him to remain calm?’ At the same time, there’s the juxtaposition of saying, ‘Well, the black person should have remained calm and complied while they had a gun pointed at them.’”

Booker, second from right, during The Power of the Black Vote, an event at City Hall on September 8 put on by Black Democrats and co-hosted by Black Lives Matter. | Courtesy photo

This and so much more raises the question: Is Vauhxx Booker proud to be an American?

“Ooh,” he says, “Donald Glover, ‘This Is America,’ is what comes to my mind. Am I proud to be an American? Yes. America is the great experiment and it’s an experiment that is still unfinished. I’m proud of what America has the capacity to be. I’m cognizant of the history of the oppression, of the nationalism, of the Manifest Destiny that has brought us to this point. My people have been here and survived every one of those incidents. Here I remain, strong and unbroken.

“We have to lift our voice. My family has been here too long and has been too strong for me to be anything less. My father was born in a time when he couldn’t vote, when there were still signs for ‘colored.’ Who would I be today to not speak against injustice? I feel a deep sense of connection between that time and this time. I see how those struggles are mine.”

Booker’s a learned man. “Malcolm X had a quote that his alma mater was books. I feel that way. It goes back to my father. He is a crossword puzzle guy. My whole life I’ve been peppered with spelling questions or questions about the Greek gods. I’m into the myths — especially Hellenistic — science and history. My aunt likes to call me a fountain of useless information.

“I just read Mississippi Harmony: Memoirs of a Freedom Fighter. It’s about voting rights, which is a deeply personal thing to me. I have a clip on my Facebook page of an uncle on my maternal side who was the first person in his Mississippi town to vote.”

The learning is never-ending. “I’m learning the political game,” Booker says. “We just had an election; I saw folks mobilize, support candidates, knock on thousands of doors, hope and dream of a better America. I’m motivated. I want to see that momentum continue to grow. I want to see the status quo challenged. I want us to think of new, innovative ways to help the most marginalized people in our community.

“I want to go ahead and enter the political arena. I’m going to launch an exploratory committee to look into running for city council. I think you’ll see that within the next 30 days.

“BLM just launched A Seat at the Table. It was a series of forums with candidates from the federal, state, and local levels. At this point, the videos have been viewed over 10,000 times. To see those candidates, to see the passion in some of their answers, and to see the disappointment that some of their answers brought me made me feel it was necessary that we have that seat at the table. It’s time we take our seat at the table and make sure our concerns are listened to.”

[Editor’s note: Michael G. Glab’s full interview with Vauhxx Booker can be heard today on his radio show, Big Talk, which runs on WFHB (91.3 FM, 98.1 Bloomington, 100.7 Nashville, 106.3 Ellettsville) every Thursday at 5:30 p.m. and will be available, along with podcasts of past shows, at WFHB.org. Each of Glab’s monthly profiles for Limestone Post is based on one of his Big Talk interviews and will be posted on the same day that the interview airs on Big Talk.]