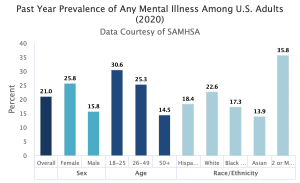

In 2020, one in five adults suffered from a mental illness in the U.S., an estimated 52.9 million adults aged 18 or older, according to National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). More women (25.8 percent) than men (15.8 percent) had a mental illness during the pandemic. But young adults 18 to 25 years old had the highest percentage of mental illness (30.6 percent) compared to adults 26 to 49 years old (25.3 percent).

The COVID-19 pandemic threw millions of people into chaos. Family members and friends died. Businesses closed. People lost jobs. Schools and universities closed. Collective grief gripped the United States and the world. All these circumstances forced people to adapt. But some did not, could not. For some, grief, depression, and social isolation overwhelmed. News headlines repeatedly warned of a mental health crisis in the United States, which continues today.

As most people know, like any other health condition, mental illness varies from person to person by the degree of severity. NIMH defines a mental illness as “a mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder” and serious mental illness as “a mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder resulting in serious functional impairment which substantially interferes with or limits one or more activities of daily life.” Because of the extent to which it can impede daily life, serious mental illness is considered a subset of 300 mental illnesses under the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Health Disorders, the main diagnostic tool for mental health practitioners. Serious mental illness includes schizoaffective disorders, schizophrenia, major depressive disorders, bipolar disorders, and others.

In 2020, approximately 14.2 million adults had a serious mental illness, and 9.1 million had received treatment in the previous year, according to NIMH. For many people, the loss of loved ones, employment, and just any semblance of a routine life threw them into disarray. For those with a serious mental illness, the pandemic compounded health issues with which they already struggled.

Addressing a mental health crisis

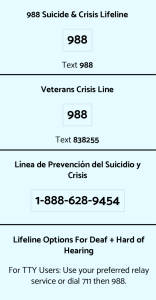

The rise in mental health cases throughout the pandemic led to a growing realization that the U.S. needed a new infrastructure to tackle growing mental health issues. As a result, a designated telephone number, 988, was adopted as an entry point for focusing on mental health crises. The phone service went into effect nationwide on July 16. Mental health advocates hope that 988 will do what 911 has already accomplished, an easy-to-remember number for those in crisis, plus a system to care for them.

In 2004, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline became the outlet for those in crisis or suicide ideation. Those in crisis called a ten-digit number to reach National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. With over 180 crisis call centers and nine national backup centers administered by Vibrant Emotional Health, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (NSPL) fielded more than 2 million calls, texts, and chats in 2020. Unfortunately, the system did not always handle the volume.

In 2004, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline became the outlet for those in crisis or suicide ideation. Those in crisis called a ten-digit number to reach National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. With over 180 crisis call centers and nine national backup centers administered by Vibrant Emotional Health, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (NSPL) fielded more than 2 million calls, texts, and chats in 2020. Unfortunately, the system did not always handle the volume.

According to the Wall Street Journal, of the more than 9 million calls received by the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline from 2016 to 2021, almost 1.5 million ended before the caller connected with a counselor. According to a STAT news article, in 2021 more than 17 percent of callers abandoned their calls to NSPL before receiving help, along with 41 percent of text messages and 73 percent of chats.

Indiana has three crisis call centers — in Gary, Lafayette, and Muncie. According to James Gavin, director of Indiana Family and Social Services Administration (FSSA), two additional locations are in the queue to become 988 call centers: Mental Health America of Indiana in Indianapolis and RemedyLIVE in Fort Wayne. Clinton Faupel, executive director of RemedyLIVE, confirmed that they are in the process of applying to be a 988 partner for call, text, and chat functions.

988 continuum of mental health care

One key difference between 911 and 988 is the mandate for 988 to develop a continuum of mental health crisis care. In the past, people experiencing a mental health crisis had two options: 911 for a law enforcement response or the emergency room for psychiatric hospitalization. But in recent years, there has been a realization, especially with the increasing numbers of incarcerated individuals with mental illness, that persons with mental health issues need more before they return to their community.

In 2019, the Federal Communications Commission proposed 988 as a three-digit number for suicide prevention. President Trump signed the Suicide Hotline Designation Act, which mandated 988 operations through the existing National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (1-800-273-8255), in October 2020.

Overall funding for 988 originates from multiple sources, such as the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) and Community Mental Health Services Block Grants. Initial appropriations amounted to $35 million. Funding in the 2022 U.S. Fiscal Year Budget provided $2.9 billion for such mental health investments as behavioral health infrastructure, children’s mental health, and community-based mental health programs.

With ongoing maintenance and infrastructure growth a concern, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) awarded $282 million in grants for 988 implementations in December 2021. Effective April 2022, the Department of Health and Human Services’ Center for Medicare and Medicaid will finance up to 85 percent in state planning grants to implement mobile crisis services for Medicaid patients. According to a Brookings Institute report, “Building a Sustainable Behavioral Health Crisis Continuum,” more than half of the states, including Indiana, have applied for these options.

Advocates such as the Mental Health Liaison Group are backing the Behavioral Health Crisis Services Expansion Act, which establishes standards for a continuum of care for persons experiencing a mental health crisis. Also, Representative Tony Cardenas (D-CA) is pushing the 988 Implementation Act, which provides funding and guidelines for states to implement their crisis response infrastructures.

Still, the federal government has delegated much of its funding to the states. In Indiana, according to Marni Lemons, deputy director of communications with FSSA, the sources for 988 funding include the state and local Fiscal Recovery Fund as appropriated by the General Assembly in the last state budget, ARPA funding for Medicaid home and community-based services, and other grants from SAMHSA.

In 2021 more than 17 percent of callers abandoned their calls to National Suicide Prevention Lifeline before receiving help, along with 41 percent of text messages and 73 percent of chats. —STAT news

A July 14 FSSA News Release announced new funding from the Indiana General Assembly in the House Enrolled Act 1001 and additional funding from ARPA and other sources. The largest investment is $54.8 million in Community Catalyst Grants, which “includes $22.3 million of local and grantee match dollars as well as $32.5 million in federal funds.”

Among the 37 grant recipients are Centerstone Brown County, Families Forever in Lawrence County, Youth First in Morgan County, and IU Health South Central Indiana (Brown, Lawrence, Monroe, and Orange counties). Finally, according to the release, Indiana will be entering into an $8 million partnership with Riley Children’s Health to provide mental health services to pediatric patients.

Indiana State Senator Shelli Yoder, D-Bloomington | Photo by Politicsislife, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

But whether or not Indiana will fund the continuum of services remains up in the air, says Indiana State Senator Shelli Yoder (D-Bloomington), a member of the Indiana Medicaid Advisory Committee and the Health and Provider Services Committee. “Historically, the Republican supermajority hasn’t put too much stock (or money) into initiatives regarding mental health,” says Yoder. “Senate Democrats have set mental health as a priority in much of their legislation over the years, but bills dealing with the subject are often sidelined by the majority party.” Still, there is some hope, says Yoder.

“Over the past two sessions especially, that concern and the necessity of mental health and substance use legislation has been proven as the lingering effects of COVID isolation, school shutdowns, and decreased financial stability have taken their toll on Hoosiers,” says Yoder. “I have seen the supermajority receive increasing pressure from our corner of the debate.”

Indiana State Representative Peggy Mayfield, R-Martinsville | Courtesy photo

But according to State Representative Peggy Mayfield (R-Martinsville), adopting the 988 helpline is “a multistep process.”

“With 2023 being a budget year, we will likely see a variety of proposals for funding, but it’s too soon to say what those might be,” says Mayfield.

As with 911, states can impose a surcharge on 988, and some states, like Virginia, Nevada, Colorado, and Washington, have enacted that fee. Indiana has not. Yoder is hoping that Democrats and Republicans will work something out, saying that it is possible that the supermajority will wait and see how this is addressed in other states.

“These services are so desperately needed by so many people,” says Yoder. “Indiana’s access to mental health services remains comparatively unimpressive — these 988 lines could save lives. My skepticism does remain, though.”

988 plan requirements

The 988 implementation plan requires three elements: (1) regional call centers that operate 24 hours a day, 365 days a year with clinically qualified staff, (2) a mobile crisis team response, and (3) crisis-receiving and -stabilization facilities. In Bloomington, the Stride Center at 312 N. Morton St. accepts those individuals needing stabilization services, says Linda Grove-Paul, vice president of Adult and Family Services at Centerstone Bloomington.

Indiana, like many states, historically has put little effort and money into its mental health system. To understand what’s behind 988, several factors have prompted this push toward building a continuum of mental health care.

According to Ready to Respond: Mental Health Beyond Crisis and Covid-19, a report by the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors (in partnership with SAMHSA), program directors identified five catalysts that prompted this movement, which, in addition to the July 16 implementation of 988, is now jumpstarting new efforts.

The first catalyst that triggered progress toward a care continuum was the consistent increase in suicide rates from year to year. For instance, according to the CDC, suicides increased by 30 percent from 2000 to 2018, but declined in 2019 and 2020. Despite this, suicide remained a leading cause of death in the U.S. in 2021.

The second and the third catalysts were the impact of COVID-19 on mental illness and the influence of the opioid epidemic. A June 2020 CDC Morbidity and Mortality Report found that during June 24-30, 2020, 41 percent of U.S. adults reported increased adverse mental health conditions associated with the pandemic. Black, Hispanic, essential-worker, and younger survey respondents age 18 to 24 years old had heightened symptoms of anxiety disorder or depressive disorder or an increase in substance abuse.

The Stride Center at 312 N. Morton St. in Bloomington will accept individuals needing stabilization services, as one of the three elements in the 988 implementation plan. The first element, regional call centers (988), are up and running. The second element, a crisis mobile team response, has been delayed until staffing issues are resolved. | Limestone Post

A recent longitudinal study, called Mental Health During the First Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Review and Recommendations for Moving Forward, examined the impact of the pandemic on mental health in its early days. In the study the Lancet’s COVID-19 Commission’s Mental Health and Wellbeing Task Force reviewed data from nearly 1,000 studies that surveyed hundreds of thousands of people from almost 100 countries. They found “a significant rise in psychological distress during the early months of the pandemic.” Especially pronounced was this distress among young female parents of children five or under.

Though numerous findings within this longitudinal study showed no increase in suicides within this period, the evidence suggested that those closer to illness, economic strain, and increased childcare and household responsibilities were at a more significant mental health risk. Others were not. In making their recommendations, the study’s authors adamantly expressed that the mental health community must concentrate on “increasing attention to mental health care over the next few years to prevent widening the gap between mental and physical health care.”

The ongoing opioid epidemic and the collision of the pandemic also saw an increasing number of overdose deaths as well as a shutdown of mental health services that impacted medication-assisted treatment and other health services available to those with substance use disorders. An increase in social isolation and financial stresses also contributed to an increase in overdoses.

A brief history of mental illness in the United States shows several factors have contributed. One, the deinstitutionalization of our mental health system, which began in the 1950s, eventually increased the incarceration of those with mental illnesses. Two, 911 became the default response to someone in crisis when appropriate facilities were unavailable.

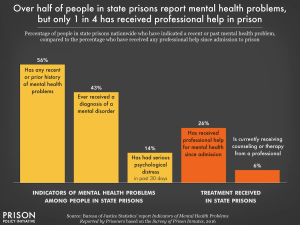

The fourth catalyst for a continuum of mental health care was people with serious mental illness or substance abuse being overrepresented in the criminal, legal, and juvenile justice systems where police officers generally lack the expertise to treat those in crisis, and guards in jail and prison facilities were generally unsuited for treatment and care for those with mental illness.

Data from the Prison Policy Initiative shows that 43 percent of those in state prisons and 44 percent in locally run jails have been diagnosed with a mental illness. In federal prisons, 66 percent have received no treatment for their condition, and in state prisons 74 percent have received no treatment. According to the U.S. Department of Justice, in 2019 suicides accounted for 30 percent of deaths in local jails and 8 percent of deaths in state and federal prisons.

Data from the Prison Policy Initiative shows that 43 percent of those in state prisons and 44 percent in locally run jails have been diagnosed with a mental illness. In federal prisons, 66 percent have received no treatment for their condition, and in state prisons 74 percent have received no treatment. According to the U.S. Department of Justice, in 2019 suicides accounted for 30 percent of deaths in local jails and 8 percent of deaths in state and federal prisons.

For those persons with mental illness outside the jail and prison system, the consequences of a lack of mental health crisis training for police officers has sometimes been deadly. According to a 2019 study in The Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, police fatally shot about 1,000 people in 2018, of which 25 percent had a mental illness.

As a result, pressure has increased to reconsider the role of law enforcement as well as jail diversion efforts. Over the past twenty years, more than 2,700 community police departments have made significant efforts to address this by using Crisis Intervention Teams, or CITs, designed to deescalate mental health crises experienced by mentally ill people. CIT is an example of an “Intercept 1” intervention within the Sequential Intercept Model (SIM). According to SAMHSA, Intercept 1 begins when law enforcement is called to respond to someone with a mental-health or substance-use disorder, and it ends when the person is either arrested or diverted into treatment. The SIM system identifies and diverts individuals from criminal processes along multiple points of interception, from contact with law enforcement to courts to reentry and community probation or parole supervision.

But several high-profile cases have arisen in recent years that have had police departments rethinking their intervention strategies and creating different models to address these issues. For instance, in Eugene, Oregon, the police department and White Bird Clinic, a federally qualified health center, have created CAHOOTS (Crisis Assistance Helping Out on the Streets), a program designed to respond as a mental health crisis intervention. White Bird Clinic, along with the Eugene police, dispatch teams of mental health clinicians with a medic when an individual’s or the public’s safety is not an issue. According to the Brookings Institute report, the new Medicaid mobile crisis incentive is modeled on CAHOOTS.

In 2020, one in five adults suffered from a mental illness in the U.S. Adults ages 18 to 25 had the highest percentage, 30.6 percent. —National Institute of Mental Health

In New York City, B-Heard, the Behavioral Health Emergency Assistance Response Division, provides targeted care for those with mental health issues. It dispatches mental health experts, social workers, and paramedics when 911 dispatchers route mental health emergency calls to B-HEARD. According to NPR, in 95 percent of the cases, people received and accepted care for mental health issues.

Melissa Stone is a social worker at the Bloomington Police Department who often makes mental health referrals to the Stride Center. | Courtesy photo

Bloomington Police Department has provided to all of its officers Integrating Communications Assessment and Tactics training, or ICAT. The training program is similar to CIT and addresses police response to volatile situations where there is erratic and possibly dangerous behavior without a firearm.

BPD has hired three social workers in recent years. Melissa Stone is one of those intervention points as a department social worker. When officers are called to a mental illness case, she and her colleagues will often be called to assess the situation and offer mental health referrals to the Stride Center. In 2021, BPD social workers received 369 referrals from officers and dispatch while working with 70 individuals/cases per month, according to BPD’s 2022 State of Public Safety report. (BPD did not respond to questions about its CIT program.) Still, the question is: How will 988 and its continuum of care change how police address these matters?

By expanding and strengthening the U.S. safety net for mental health care, 988 will be the starting point in this continuum of care. Once established, its mobile crisis teams will address those on the street with mental health emergencies that police often respond to, and then divert that care to a stabilization center rather than a jail cell. It takes the stress off of police and puts pressure on those qualified to address mental health crises. “Law enforcement, Statehouse colleagues, and health care professionals are all in agreement that the need for services is dire and that ERs and jails cannot continue to serve as our frontline solution for mental health and substance use disorders,” says Yoder.

Grove-Paul agrees. In Bloomington, she sees the Stride Center working with BPD to work through these issues. A 911 dispatcher can forward calls to 988. They are hoping to divert, if necessary, people with a crisis to 988 and Stride Center to keep from having any contact with law enforcement, says Grove-Paul. “It’s part of the whole comprehensive continuum,” she says. In fact, according to their Public Safety report, BPD referred 52 percent (156 individuals) of the total number of people assisted by Stride since the center opened in January 2020.

Finally, the fifth catalyst toward building a continuum of mental health care has been the overwhelming need, especially among young adults waiting to access inpatient psychiatric care from a hospital waiting room. According to the Ready to Respond report by state mental health program directors, many states face litigation because of failing to meet Medicaid’s statutory requirement of early screening and placement for Medicaid patients. The CDC says only 20 percent of children and young adults have access to care for mental, behavioral, and emotional issues.

The bottom line, says Grove-Paul, is that the current system has not been structured to help people in crisis because funding for the current national suicide lifeline has been cobbled together. As a result, there is no structure for dealing with mental health crises and connecting people to a “robust continuum of care.”

Critical aspects of 988 implementation

With the implementation of 988 and its corresponding crisis services, Grove-Paul says, “we’re now building a brand new infrastructure of support that is so desperately needed but has never been here.” That infrastructure contains three components: 988, mobile crisis teams, and a crisis stabilization center. So it may be like starting from scratch, but Bloomington already has plenty of resources available to incorporate within this system, says Grove-Paul.

Linda Grove-Paul, vice president of Adult Services at Centerstone in Bloomington, says regional 988 call centers with qualified crisis teams can answer and respond to crisis calls. “We’re now building a brand new infrastructure of support that is so desperately needed but has never been here.” | Courtesy photo

Regional call centers with qualified crisis teams can answer and respond to crisis calls, and text and chat will also be available, says Grove-Paul. These individuals will “deescalate the situation, so the expectation is you have a place to call, and about eighty percent of the time, we expect that crisis will be resolved with just a phone call.” SAMSHA forecasts a 14 percent annual growth rate of calls to 988.

When they cannot deescalate the situation, says Grove-Paul, they will have a mobile team at the Stride Center available to respond 24/7/365. Columbus will also have a second Stride Center with mobile staff doing the same thing.

Those needing inpatient care will be cared for at the Stride Center, the third component of 988 and its continuum of services. For those under 18 years old, the options now are limited. “We hope to determine the need for the under-18 population better, once we get started,” says Grove-Paul. “If we determine there is a need for a place for the under 18 individuals, we will work to find an appropriate partner to try to support it.”

These mental health services will be available not only in Bloomington but in neighboring counties of Brown, Morgan, Owen, and Lawrence, says Grove-Paul.

Problems facing 988 implementation

Notwithstanding the funding issue, the biggest problem that Grove-Paul is facing right now is finding qualified staffing for these positions. Staffing the second and third shifts has been the most challenging. “As far as implementing mobile crisis, we are delayed somewhat due to staffing issues,” says Grove-Paul. “We have the ability to respond to calls, but having staff to physically deploy 24/7 will be limited until all positions are filled, and staff trained.”

Grove-Paul is not alone in these challenges. In June 2021, the Ready to Respond report found that 64 percent of state mental health leaders surveyed said they were concerned about workforce shortages impacting 988 implementations. In addition, 52 percent had rural or geographic concerns for mobile crisis teams, and 36 percent identified insufficient crisis system infrastructure as a barrier. Overall, an estimated 122 million people in the U.S. live in what is designated as a “shortage area,” meaning that these areas have failed to meet the needed criteria and ratios given their population, plus the prevalence of poverty, alcoholism, and substance abuse.

For Grove-Paul, making 988 successful and solidifying that continuum of mental health care with community partners is an important goal. “I think some people are expecting a switch is going to be flipped on,” says Grove-Paul. “The system is complex. There are a lot of challenges to getting people help when the system has not been structured to help people in crisis. A lot of infrastructures still have to be put into place.”

The Bloomington Health Foundation is an underwriting partner of Limestone Post. As the local philanthropic expert for improving community health for more than 50 years, Bloomington Health Foundation is expanding its mission to address the most pressing health needs in Bloomington and neighboring communities.

The Bloomington Health Foundation is an underwriting partner of Limestone Post. As the local philanthropic expert for improving community health for more than 50 years, Bloomington Health Foundation is expanding its mission to address the most pressing health needs in Bloomington and neighboring communities.