Most family albums are a form of propaganda, where

the family looks perfect and everybody is smiling.

—Martin Parr

Most of us keep thoughts of mortality, especially our own, at arm’s length. Death can wait for another day. Watching the decline and death of a beloved parent, however, has a way of concentrating our attention on our common fate. But what if that death is balanced with the ultimate affirmation of life? The birth of an infant — the genesis of a new generation?

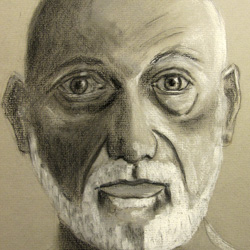

Throughout his career, Indiana University artist-educator James Osama Nakagawa has captured profound life changes in his photography. | Courtesy photo

In 1998, shortly after learning his father had terminal cancer, Osamu James Nakagawa and his wife, Tomoko, welcomed their daughter into the world. Nakagawa, who grew up in Tokyo and Houston, always felt suspended between two cultures. He used photography to buffer himself against a nagging sense of not belonging. At the age of 36, he faced a different suspension, wrenched apart by death and life, grief and joy, past and future.

Unprepared for such profound life changes, he turned again to photography, creating two major projects about family: Kai: Following the Cycle of Life; and Ma: Between the Past. Together they demonstrate the range of this artist’s oeuvre: black-and-white film versus digital color, straight versus manipulated collage, original content versus appropriated images, immediate versus extended family.

***

Nakagawa’s Kai images are featured in “A Shared Elegy,” an exhibition of work by four related photographers — father and son, nephew and uncle — at Indiana University’s Grunwald Gallery of Art, from October 13 to November 16. (See the end of this story for more information on “A Shared Elegy.”)

Since joining IU in 1998, Nakagawa has impacted its fine arts photography program in major ways: leading the transition from wet-chemistry darkrooms to digital imaging, establishing an overseas study program in Osaka, Japan, bringing numerous international photographers and curators to campus to lecture and meet with students, and mentoring scores of MFA graduates. As the Ruth N. Halls Distinguished Professor of Photography in IU’s School of Art, Architecture + Design (SAA+D), he coordinates the school’s photography sequence and directs the Center for Integrative Photographic Studies.

The recipient of many grants and awards, including a Guggenheim Fellowship, Nakagawa has exhibited in numerous solo and group exhibitions and in international photography festivals and biennales in New York City, France, Australia, Taiwan, Japan, and the Netherlands.

“Morning Light,” Bloomington, Indiana, 1999, from the series Kai: Following the Cycle of Life. | Photo courtesy of Osamu James Nakagawa

Of his dual role, he says, “As an artist, I always try to push beyond my own expectations to discover a visual language that honestly communicates. When I see my students engage in this same process, I feel that I have succeeded as an artist-educator.”

Nakagawa is also a major presence in the local visual arts community, exhibiting several times at Bloomington’s Pictura Gallery. He’s excited about the new FAR (Fourth and Rogers) Center for Contemporary Arts, the latest venture by Pictura owners David and Martha Moore, commenting, “This will bring many international, national, and area art and theater figures to this town I call home.”

Perhaps one reason for Nakagawa’s feeling of suspension is that some important concepts do not migrate easily across cultural borders. As his SAA+D colleague, Rowland Ricketts, a textile artist who lived in Japan for many years, explains, “Nakagawa titles his works in romanized Japanese, in words that to the English speaker are merely sounds. To the Japanese speaker, however, titles like Kai embody a worldview imbued with the Buddhist idea of our existing each moment in a constantly changing cycle of birth, life, death, and rebirth. Like Nakagawa’s images, these titles reflect his own life experience in an evolving liminal space, Ma, between Japan and America.”

***

Kai, Japanese for “cycle,” began first. In April 1998, in Japan for the opening of his group exhibition, “Media Logue: Photography in Contemporary Japan,” at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, Nakagawa noticed swelling in the legs of his father, Takeshi, and insisted he see a doctor. After tests, his father confided, “Don’t tell your mother, but if the shadow in my lung doesn’t disappear, then probably it’s cancer.” A few weeks later, Nakagawa’s daughter Hikari was born in Houston, and, almost simultaneously, he was called to interview for a position at IU’s School of Fine Arts. “It was a crazy time,” he remembers. “Everything was happening at once.”

“Hot Springs,” Hakone, 1998, from the series Kai: Following the Cycle of Life. | Photo courtesy of Osamu James Nakagawa

Born in 1928, Nakagawa’s father became a navy officer toward the end of World War II, but never saw combat. He helped rebuild postwar Japan’s economy, rising through the ranks at the Mitsubishi Corporation to become head of its Houston operations. From there, the conglomerate assigned him to Mexico City, where he oversaw its Central and South American operations.

Seven months after his birth in New York City, Nakagawa and his family moved to Tokyo. When he was 15, they relocated to Houston. Speaking no English, he drew pictures to communicate with his classmates. Later, as an adult, Nakagawa resorted again to pencil and sketchbook when discussing a potentially awkward situation with his father. As his father’s cancer rapidly progressed, Nakagawa knew he wanted to photograph him at a spa where he frequently bathed. Given Takeshi’s background as an officer and accomplished businessman, Nakagawa worried he would refuse to pose nude, so he explained the photograph he wanted by drawing a sketch.

“He woke me at 6 a.m. on the day before he entered the hospital for chemotherapy,” Nakagawa recalls. When they arrived, Takeshi nervously asked where he should stand. Bathed in soft light, he stands before a large fountain. He holds a towel across his pelvis, his tanned arms framing his light torso. Solemn, vulnerable, but with profound dignity, he turns inward in introspection. The photograph transcends any personal relationship. “To me, it’s a very Japanese portrait,” Nakagawa says. “The towel and dignity capture some essence of Japaneseness. He’s my father, but other Japanese can identify their own fathers in his stance and expression.”

“Kai, Ninomiya,” 1998, from the series Kai, Following the Cycle of Life. | Photo courtesy of Osamu James Nakagawa

Shortly after his father’s death, Nakagawa took a symbolic image that encompasses three generations. Near the family home in Ninomiya, Tomoko stands where the ocean meets a lowering sky, their daughter at her breast. Balanced against her hip is his father’s funeral portrait. She holds a white lily from the funeral in her right hand and reassuringly offers her left index finger to their daughter. As she looks toward the left, Hikari and Takeshi appear to confront our gaze. “I didn’t know what I had done,” Nakagawa says. “I didn’t know the power of that image,” until much later.

Kai’s delightful images include one showing their daughter, surrounded by stuffed toys and playing with a camera as the shadows of her parents bow toward her. Other photographs, however, would seem out of place in a typical family album: chest X-rays, IV tubes, ultrasound images, and contact sheets scattered across a gravestone. Beyond their square format and exquisite tonal values, what unites these images is an oblique vision that constantly challenges our expectations.

Before entering the hospital, Takeshi gathered his two sons. He handed a suitcase to James, asking him to take care of it. It was filled with family photographs, negatives, and 8mm movie film Takeshi had taken of his children. Consumed with a new baby and a new job, Nakagawa put the suitcase away. On academic leave in 2003, he finally opened it and began working.

Ma, Japanese for “between,” holds a complex meaning for Nakagawa: “I took lots of photographs with the Leica — snaps,” he says. “So I started thinking, ‘What did those images trigger?’” In the old film tradition, he circled strong images on his contact sheets. But what about “all the stuff you don’t circle,” the frames in between? “So that, I think, is Ma. Those photographs are memory triggers for me,” he explains.

“Castle,” 2003-2005, from the series Ma: Between the Past. | Photo courtesy of Osamu James Nakagawa

At first, he combined these “not-so-good photographs” with the inherited family photographs, making twenty 11-by-40-inch triptychs, but he wasn’t satisfied. His father’s 8mm film provided a breakthrough, letting him merge traditional Japanese culture with images from his own childhood. This film was significant for two reasons. Nakagawa’s father had bought the movie camera in New York before such items were available in Japan. “For him, I think, it symbolized the American good life,” he speculates. The film also had bittersweet associations. After subjecting the children to his strict navy discipline, his father would reconcile with them by gathering the family to watch these home movies.

“Rain,” 2003-2005, from the series Ma: Between the Past. | Photo courtesy of Osamu James Nakagawa

Castle provides a good example of Ma. Nakagawa’s paternal grandfather had gone to live with a wealthy family in Osaka that sponsored his education. Around 1917, they built a huge mansion. During the ritual Shinto blessing, carpenters perched on the wooden framework while family members, friends, and employees arranged themselves at ground level wearing the solemn expressions of a formal portrait.

Using Photoshop, Nakagawa cut and expanded the image. Into the interstices, he collaged 12 strips of movie film that his father had taken on a family vacation to Disneyland. Against the brown-toned photograph, these pink and blue strips contrast the Japanese mansion to a western fantasy castle with turrets, parapets, crenellations, and cone roofs. Nakagawa truncates the strips but implies their continuation by mimicking their shape. Keeping these areas translucent, he lets us see how he divided and doubled people to fill the expansions. He juxtaposes traditional Japan with American popular culture, unknown ancestors with his own childhood.

A second Ma image, from the childhood of his mother, Yoko, shows her and her father, third from right, mounted on donkeys and surrounded by his brothers and employees. Nakagawa overlays it with movie strips that abut horizontally, but have vertical gaps. Their blur suggests rain, and he chose that as the image’s title.

“Final Conversation,” Tokyo, 2013, from the series Kai, Following the Cycle of Life. | Photo courtesy of Osamu James Nakagawa

Based in digital, Ma is closer to Nakagawa’s primary working method than Kai. He began digital photography as an MFA student at the University of Houston in the early 1990s. The first year, his class shared a single computer with 25 megahertz of power. Their images were one megabyte. Photoshop didn’t exist, and they didn’t have a scanner. Despite these limitations, Nakagawa found early success, digitally collaging images of American culture onto pictures of drive-in movie screens and billboards. His master’s thesis, Drive-in Theater and Billboard, garnered accolades in numerous international exhibitions, plus reviews in Aperture, The New York Times, Time Magazine, Asahi Camera, and Nippon Camera.

After Ma, he moved beyond collage. His Banta (Cliffs) and Gama (Caves) series evoke the violence of the Japanese occupation of Okinawa near the end of WWII. He digitally tones, colorizes, and stitches together numerous exposures, producing images that appear straight but would be impossible to capture in a single frame. Like his earlier work, these images are rooted in a strong photographic tradition but their subtle perspectival shifts challenge our understanding of what photography can be in a rapidly expanding technological environment.

Train Ride, Tokyo, 2013, from the series Kai, Following the Cycle of Life. | Photo courtesy of Osamu James Nakagawa

In 2010, as his mother’s health began to decline, Nakagawa started a second chapter of Kai. He kept the square format, but photographed in digital color. In a role reversal that might be a premonition, one image shows his fatigued wife sleeping on the shoulder of a strong, confident Hikari as they ride a Japanese train.

Notwithstanding other photos of his wife and daughter, Nakagawa concentrates primarily on his mother Yoko. He shows her face, badly bruised from a fall, and records her with a defiant expression that belies the cast on her arm. We see her hair clippings, a tangle of nylons, her bottle of Amour perfume, and her posthumously empty walker washed by the Ninomiya surf. In a subtle self-portrait, Nakagawa photographs his reflection in the glass framing one of his mother’s flower paintings.

“Right before my mother passed away,” Nakagawa recalls, “she was breathing heavily, and I was talking to her while I took photographs. I probably took 50 images with a very slow shutter, intentionally blurring the image to visualize my emotion.” The photo Final Conversation, he says, “is the only one where she is making eye contact with me.”

As the color faded from her body, Nakagawa photographed his mother’s tiny hand with its paper-thin skin against his own. It was his final encounter with the hands that fed him, supported him as he learned to walk, nursed his accidents, applauded his childhood achievements and adult successes. Such content is rarely seen since the practice of mortuary photography in the 19th century, when most people died at home surrounded by loved ones, and survivors were not insulated from death.

(l-r) “Self Portrait with My Mother’s Painting,” Tokyo, 2012. “By Her Room,” Tokyo, 2013. “Mother’s Hand,” Tokyo, 2013. From the series Kai, Following the Cycle of Life. | Photos courtesy of Osamu James Nakagawa

Referencing such Kai photographs, a friend told Nakagawa she could never photograph her own parents in death. Nakagawa could not escape the compulsion to take these photographs. They are not, in the words of Martin Parr, propaganda intended to make his family look perfect. Deeply personal, they affirm universal experiences. True art, they force us to confront realities we might prefer to avoid. Combining formal beauty with sometimes wrenching content, they celebrate the family in sorrow and joy.

They exemplify the artist as seer.

***

An earlier version of this article originally appeared in the Spring 2017 (50:1) issue of Exposure, the journal for the Society for Photographic Education.

‘A Shared Elegy’

“A Shared Elegy,” an exhibition of photographs revealing universal family themes, opens at Indiana University’s Grunwald Gallery of Art October 13. It presents the insights of four photographers — a father and son, nephew and uncle — exploring family ties across generations.

Osamu James Nakagawa, the Ruth N. Halls Distinguished Professor of Photography at Indiana University, and his uncle, Takayuki Ogawa, who lived and worked in New York City for many years, offer work enriched by their cross-cultural experiences.

Internationally known photographer Emmet Gowin and his son Elijah explore their family’s heritage in Virginia, revealing the intimate and hallowed nature of rural life.

Despite the photographers’ cultural differences, their images uncover universals of the human condition from birth and childhood to aging, illness, and death. Their honest confrontation of humanity’s common fate balances more joyful images. Their photographs compel us to reflect on our own place in the progression of generations and the cycle of life and death.

A joint presentation of the Grunwald Gallery and the IU Eskenazi Museum of Art, the exhibition continues through November 16. A Shared Elegy, a 112-page book published by Indiana University Press, accompanies the exhibition.

A panel discussion featuring Nakagawa and the Gowins is scheduled from 3 to 4:30 p.m., October 13, in Room 015 of the IU School of Art, Architecture + Design Building, 1201 E. 7th St. Emmet Gowin will deliver the McKinney Lecture from 5 to 6 p.m., in the same venue. The opening reception will be from 6 to 8 p.m., in the Grunwald Gallery, in the same building.